May 1 2008

An international team of physical oceanographers including a researcher from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego has discovered that oxygen-poor regions of tropical oceans are expanding as the oceans warm, limiting the areas in which predatory fishes and other marine organisms can live or enter in search of food.

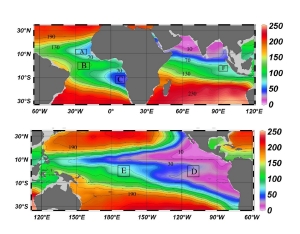

Mean dissolved oxygen concentrations in the world's oceans at a depth of 400 meters (1,312 feet) with blue contours representing the lowest concentrations. Boxed areas represent ocean regions analyzed in the study. Image courtesy of AAAS/Science

Mean dissolved oxygen concentrations in the world's oceans at a depth of 400 meters (1,312 feet) with blue contours representing the lowest concentrations. Boxed areas represent ocean regions analyzed in the study. Image courtesy of AAAS/Science

The new study is led by Lothar Stramma from the Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences (IFM-GEOMAR) in Kiel, Germany, and is co-authored by Janet Sprintall, a physical oceanographer at Scripps Oceanography and others. The researchers found through analysis of a database of ocean oxygen measurements that levels in tropical oceans at a depth of 300 to 700 meters (985 to 2,300 feet) have declined during the past 50 years. The ecological impacts of this increase could have substantial biological and economical consequences.

“We found the largest reduction in a depth of 300 to 700 meters (985 to 2,300 feet) in the tropical northeast Atlantic, whereas the changes in the eastern Indian Ocean were much less pronounced,” said Stramma. “Whether or not these observed changes in oxygen can be attributed to global warming alone is still unresolved. The reduction in oxygen may also be caused by natural processes on shorter time scales.”

Sprintall said the oxygen-poor areas have the potential to move into coastal areas via currents that flow from the mid-depth tropical oceans, where the oxygen changes were observed, and along the west coast of continents.

“The width of the low-oxygen zone is expanding deeper but also shoaling toward the ocean surface,” said Sprintall, a specialist in observing changes of fluxes in ocean properties such as heat distribution.

Sprintall contributed data to the study gathered during recent cruises undertaken as part of the Climate Variability and Predictability (CLIVAR) program, a long-running study operated by the World Climate Research Programme that seeks to understand climate through ocean-atmosphere interactions.

The study, “Expanding Oxygen-Minimum Zones in the Tropical Oceans,” appears in the May 2 edition of the journal Science. The research team includes Stramma, Sprintall, NOAA scientist Gregory Johnson, and Volker Mohrholz from the Institute for Baltic Sea Research in Warnemünde, Germany.

The team selected ocean regions for which they could obtain the greatest amount of data to document the decline in oxygen. Some of the more recent data came from oxygen sensors which have been added to about 150 of the profiling floats used in Argo, a worldwide network of sensors that track basic ocean conditions such as temperature and salinity. There are more than 3,000 Argo floats operating in the world’s oceans, and Sprintall said the quality of the data gathered by the Argo floats suggests that more units in the network should be outfitted with oxygen sensors.

Lisa Levin, a biological oceanographer at Scripps Oceanography who studies oxygen-minimum zones that intercept the seafloor, said an expansion of oxygen-minimum zones in the oceans could lead to diminished biodiversity and to the expanded distributions of organisms that have adapted to live in hypoxic, or oxygen-poor waters.

“I think it’s uncharted territory,” said Levin, who was not affiliated with the study. “Thicker oxygen minimum zones could affect nutrient cycling, predator-prey relationships and plankton migrations. Where the expanding oxygen-minimum zones impinge on continental margins, we could see huge ecosystem changes.”

The results of the study are an important milestone for the ongoing work of the new Collaborative Research Centre (SFB 754) “Climate – Biogeochemistry Interactions in the Tropical Ocean” funded by the German Research Foundation, which started its first phase in January 2008 in close cooperation with the University of Kiel. The SFB aims to better define the interactions between climate and biogeochemistry on a quantitative basis.