Dec 11 2014

It's widely known that the Earth's average temperature has been rising. But research by an Indiana University geographer and colleagues finds that spatial patterns of extreme temperature anomalies -- readings well above or below the mean -- are warming even faster than the overall average.

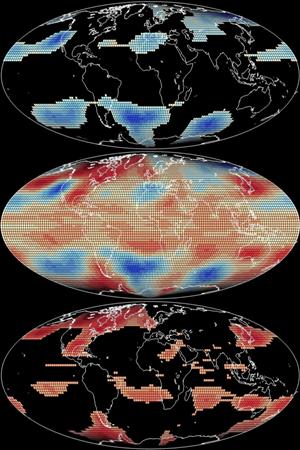

The middle panel illustrates spatial patterns of temperature anomalies for April 1998. The top panel shows locations that are below the 25th percentile, and the bottom panel shows locations that are above the 75th percentile. Credit: Scott Robeson, Indiana University

The middle panel illustrates spatial patterns of temperature anomalies for April 1998. The top panel shows locations that are below the 25th percentile, and the bottom panel shows locations that are above the 75th percentile. Credit: Scott Robeson, Indiana University

And trends in extreme heat and cold are important, said Scott M. Robeson, professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. They have an outsized impact on water supplies, agricultural productivity and other factors related to human health and well-being.

"Average temperatures don't tell us everything we need to know about climate change," he said. "Arguably, these cold extremes and warm extremes are the most important factors for human society."

Robeson is the lead author of the article "Trends in hemispheric warm and cold anomalies," which will be published in the journal Geophysical Review Letters and is available online. Co-authors are Cort J. Willmott of the University of Delaware and Phil D. Jones of the University of East Anglia.

The researchers analyzed temperature records for the years 1881 to 2013 from HadCRUT4, a widely used data set for land and sea locations compiled by the University of East Anglia and the U.K. Met Office. Using monthly average temperatures at points across the globe, they sorted them into "spatial percentiles," which represent how unusual they are by their geographic size.

Their findings include:

- Temperatures at the cold and warm "tails" of the spatial distribution -- the 5th and 95th percentiles -- increased more than the overall average Earth temperature.

- Over the 130-year record, cold anomalies increased more than warm anomalies, resulting in an overall narrowing of the range of Earth's temperatures.

- In the past 30 years, however, that pattern reversed, with warm anomalies increasing at a faster rate than cold anomalies.

"Earth's temperature was becoming more homogenous with time," Robeson said, "but now it's not."

The study records separate results for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Temperatures are considerably more volatile in the Northern Hemisphere, an expected result because there's considerably less land mass in the South to add complexity to weather systems.

The study also examined anomalies during the "pause" in global warming that scientists have observed since 1998. While a 16-year-period is too short a time to draw conclusions about trends, the researchers found that warming continued at most locations on the planet and during much of the year, but that warming was offset by strong cooling during winter months in the Northern Hemisphere.

"There really hasn't been a pause in global warming," Robeson said. "There's been a pause in Northern Hemisphere winter warming."

Co-author Jones of the University of East Anglia said the study provides scientists with better knowledge about what's taking place with the Earth's climate. "Improved understanding of the spatial patterns of change over the three periods studied are vital for understanding the causes of recent events," he said.

It may seem counterintuitive that global warming would be accompanied by colder winter weather at some locales. But Robeson said the observation aligns with theories about climate change, which hold that amplified warming in the Arctic region produces changes in the jet stream, which can result in extended periods of cold weather at some locations in the mid-northern latitudes.

And while the rate of planetary warming has slowed in the past 16 years, it hasn't stopped. The World Meteorological Organization announced this month that 2014 is on track to be one of the warmest, if not the warmest, years on record as measured by global average temperatures.

In the U.S., the East has been unusually cold and snowy in recent years, but much of the West has been unusually warm and has experienced drought. And what happens here doesn't necessarily reflect conditions on the rest of the planet. Robeson points out that the United States, including Alaska, makes up only 2 percent of the Earth's surface.