Feb 11 2016

The weather patterns that typically bring moisture to the southwestern United States are becoming more rare, an indication that the region is sliding into the drier climate state predicted by global models, according to a new study.

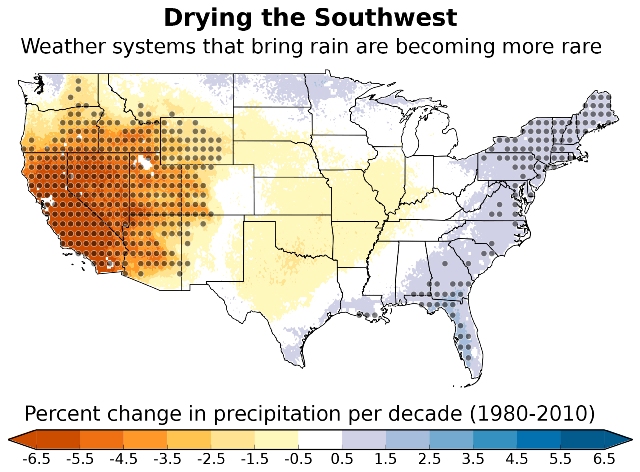

Weather systems that typically bring moisture to the southwestern United States are forming less often, resulting in a drier climate across the region. This map depicts the portion of overall changes in precipitation across the United States that can be attributed to these changes in weather system frequency. The gray dots represent areas where the results are statistically significant. (Map courtesy of Andreas Prein, NCAR.

Weather systems that typically bring moisture to the southwestern United States are forming less often, resulting in a drier climate across the region. This map depicts the portion of overall changes in precipitation across the United States that can be attributed to these changes in weather system frequency. The gray dots represent areas where the results are statistically significant. (Map courtesy of Andreas Prein, NCAR.

"A normal year in the Southwest is now drier than it once was," said Andreas Prein, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) who led the study. "If you have a drought nowadays, it will be more severe because our base state is drier."

Climate models generally agree that human-caused climate change will push the southwestern United States to become drier. And in recent years, the region has been stricken by drought. But linking model predictions to changes on the ground is challenging.

In the new study—published online today in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, a publication of the American Geophysical Union—NCAR researchers grapple with the root cause of current drying in the Southwest to better understand how it might be connected to a warming climate.

Subtle shift yields dramatic impact

For the study, the researchers analyzed 35 years of data to identify common weather patterns—arrangements of high and low pressure systems that determine where it's likely to be sunny and clear or cloudy and wet, among other things. They identified a dozen patterns that are typical for the weather activity in the contiguous United States and then looked to see whether those patterns were becoming more or less frequent.

"The weather types that are becoming more rare are the ones that bring a lot of rain to the southwestern United States," Prein said. "Because only a few weather patterns bring precipitation to the Southwest, those changes have a dramatic impact."

The Southwest is especially vulnerable to any additional drying. The region, already the most arid in the country, is home to a quickly growing population that is putting tremendous stress on its limited water resources.

“Prolonged drought has many adverse effects,” said Anjuli Bamzai, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, which funded the research, “so understanding regional precipitation trends is vital for the well-being of society. These researchers demonstrate that subtle shifts in large-scale weather patterns over the past three decades or so have been the dominant factor in precipitation trends in the southwestern United States.”

The study also found an opposite, though smaller, effect in the Northeast, where some of the weather patterns that typically bring moisture to the region are increasing.

“Understanding how changing weather pattern frequencies may impact total precipitation across the U.S. is particularly relevant to water resource managers as they contend with issues such as droughts and floods, and plan future infrastructure to store and disperse water,” said NCAR scientist Mari Tye, a co-author of the study.

The climate connection

The three patterns that tend to bring the most wet weather to the Southwest all involve low pressure centered in the North Pacific just off the coast of Washington, typically during the winter. Between 1979 and 2014, such low-pressure systems formed less and less often. The associated persistent high pressure in that area over recent years is a main driver of the devastating California drought.

This shift toward higher pressure in the North Pacific is consistent with climate model runs, which predict that a belt of higher average pressure that now sits closer to the equator will move north. This high-pressure belt is created as air that rises over the equator moves poleward and then descends back toward the surface. The sinking air causes generally drier conditions over the region and inhibits the development of rain-producing systems.

Many of the world's deserts, including the Sahara, are found in such regions of sinking air, which typically lie around 30 degrees latitude on either side of the equator. Climate models project that these zones will move further poleward. The result is a generally drier Southwest.

While climate change is a plausible explanation for the change in frequency, the authors caution that the study does not prove a connection. To examine this potential connection further, they are studying climate model data for evidence of similar changes in future weather pattern frequencies.

"As temperatures increase, the ground becomes drier and the transition into drought happens more rapidly,” said NCAR scientist Greg Holland, a co-author of the study. “In the Southwest the decreased frequency of rainfall events has further extended the period and intensity of these droughts.”

The study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation, NCAR's sponsor, and the Research Partnership to Secure Energy for America.

Other co-authors of the study include NCAR scientists Roy Rasmussen and Martyn Clark.