Apr 24 2019

High concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the air blowing out to sea from cities and agricultural regions, including Silicon Valley were recently noted by scientists at MBARI measured. In a new paper in PLOS ONE, they calculate that this formerly unrecorded process could increase the amount of CO2 dissolving into coastal ocean waters by approximately 20%.

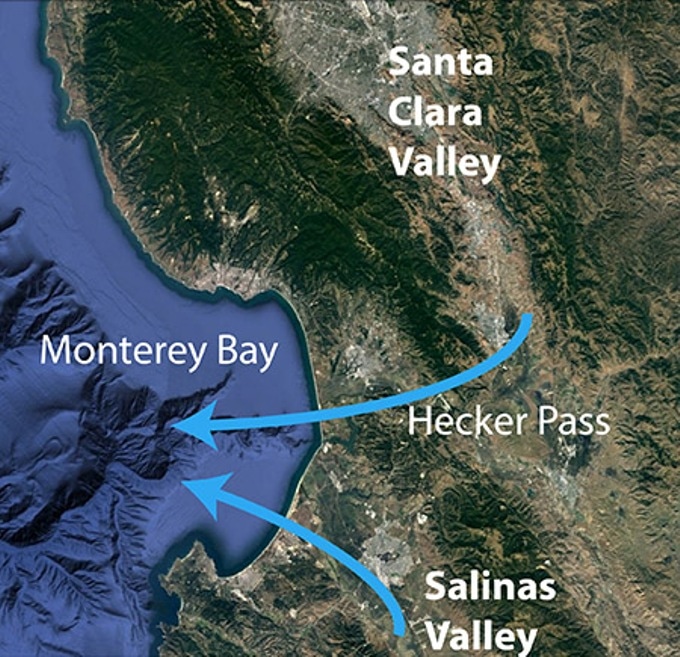

This map shows how carbon dioxide from the land flows out across Monterey Bay with morning land breezes. (Base image credit: Google Earth)

This map shows how carbon dioxide from the land flows out across Monterey Bay with morning land breezes. (Base image credit: Google Earth)

Extending their calculations to coastal regions globally, the scientists estimate that this process could add 25 million extra tons of CO2 to the ocean annually, which would make up for roughly 1% of the ocean’s total yearly CO2 uptake. This effect is not presently included in calculations of how much CO2 is going into the ocean due to the burning of fossil fuels.

Less than half of the CO2 that humans have discharged in the past 200 years has stayed in the atmosphere. The rest has been absorbed in nearly equal proportions by the terrestrial and ocean ecosystems. How rapidly CO2 enters the ocean in any specific area is based on several factors, including the temperature of the water, the wind speed, and the relative concentrations of CO2 in the surface waters and in the air right above the sea surface.

Virtually continuously since 1993 MBARI has been measuring CO2 concentrations in the air and seawater of Monterey Bay. But it was not until 2017 that scientists started examining carefully the atmospheric data collected from sea-surface robots.

One of our summer interns, Diego Sancho-Gallegos, analyzed the atmospheric carbon dioxide data from our research moorings and found much higher levels than expected. If these measurements had been taken on board a ship, researchers would have thought the extra carbon dioxide came from the ship’s engine exhaust system and would have discounted them. But our moorings and surface robots do not release carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

Francisco Chavez, Biological Oceanographer, MBARI.

In early 2018, MBARI Research Assistant Devon Northcott began working on the data set, examining hourly CO2 concentrations in the air spanning Monterey Bay. He observed another striking pattern—CO2 concentrations increased in the early morning.

Although atmospheric researchers had earlier witnessed early-morning peaks in CO2 concentrations in a few cities and agricultural regions, this was the first time such peaks had been noted over ocean waters. The finding also opposed a basic scientific assumption that concentrations of CO2 over ocean areas do not differ much over space or time.

Northcott could track down the sources of this additional CO2 using measurements made from a robotic surface vessel referred to as a Wave Glider, which travels to and fro across Monterey Bay making measurements of CO2 in the air and ocean for weeks at a stretch.

Because we had measurements from the Wave Glider at many different locations around the bay. I could use the Wave Glider’s position and the speed and direction of the wind to triangulate the direction the carbon dioxide was coming from.

Devon Northcott, Research Assistant, MBARI.

The data proposed two key sources for the morning peaks in CO2—the Salinas and Santa Clara Valleys. The Salinas Valley is one of the largest agricultural areas in California, and many plants discharge CO2 at night, which may explain why there was additional CO2 in the air from this area. Santa Clara Valley [aka Silicon Valley] is a dense urban area, where light winds and other atmospheric environments in the early morning could concentrate CO2 discharged from factories and cars.

Usual morning breezes blow straight from the Salinas Valley out across Monterey Bay. Morning breezes also bring air from the Santa Clara Valley southward and then west via a gap in the mountains (Hecker Pass) and out across Monterey Bay.

We had this evidence that the carbon dioxide was coming from an urban area. But when we looked at the scientific literature, there was nothing about air from urban areas affecting the coastal ocean. People had thought about this, but no one had measured it systematically before.

Devon Northcott, Research Assistant, MBARI.

The scientists do not view this paper as the last word, but as a “wake-up call” to other scientists.

This brings up a lot of questions that we hope other researchers will look into. One of first and most important things would be to make detailed measurements of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and ocean in other coastal areas. We need to know if this is a global phenomenon. We would also like to get the atmospheric modelling community involved. We’ve estimated that this could increase the amount of carbon dioxide entering coastal waters by roughly 20 percent. This could have an effect on the acidity of seawater in these areas. Unfortunately, we don’t have any good way to measure this increase in acidity because carbon dioxide takes time to enter the ocean and carbon dioxide concentrations vary dramatically in coastal waters. There must be other pollutants in this urban air that are affecting the coastal ocean as well. This is yet another case where the data from MBARI’s autonomous robots and sensors has led us to new and unexpected discoveries. Hopefully, other scientists will see these results and will want to know if this is happening in their own backyards.

Francisco Chavez, Biological Oceanographer, MBARI.