Sep 17 2019

Land restoration in the Caribbean and Latin America is gaining momentum and scaling up projects will help the region to adhere to its pledges under the Bonn Challenge, which intends to restore 350 million hectares of deforested and degraded land globally by 2030.

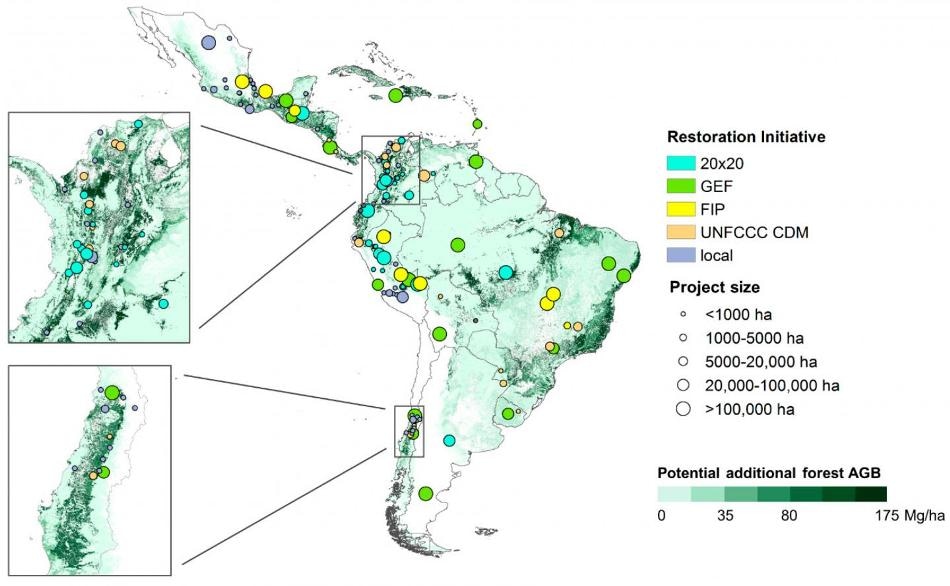

The map shows the location of 154 land restoration projects in Latin America and the Caribbean that were part of this study. (Image credit: Erika Romijn et al.)

The map shows the location of 154 land restoration projects in Latin America and the Caribbean that were part of this study. (Image credit: Erika Romijn et al.)

New research, led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and Wageningen University, provides the first map of restoration projects in Latin America and reveals their potential to alleviate climate change through restoring forests.

Scientists took into consideration the goals, location, and activities of 154 projects in Latin America and the Caribbean, starting a database to direct practitioners in expanding restoration. They mapped projects under five initiatives working towards the Bonn Challenge goals—the 20x20 Initiative, the Global Environment Facility, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), the Forest Investment Program (FIP) and independent local projects—along with mapping the potential biomass increase that forest restoration could attain across the region's different ecosystems.

We're asking a lot from the land, to produce food for another couple of billion people. We also don't want to lose more forest. We need to make more out of the land that we have. The IPCC 1.5 °C report made clear how fast we need to take carbon out of the atmosphere. To do that, you have to do something about land emissions.

Louis Verchot, Study Co-Author and Agroecosystems and Sustainable Landscapes Researcher, CIAT

Verchot is also a leading contributor to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s latest Climate Change and Land report.

In Latin America, a number of the planned or ongoing projects are in regions where there is great potential for increased biomass, such as the subtropical and tropical forest ecosystems on the edges of the Southeast Brazil, Amazon Basin, and Central America. While all projects can offer more forest biomass for carbon sequestration, the outcome reveals that FIP, CDM, and local projects have the biggest capacity to accomplish that.

In addition, local-level projects focused on areas with high carbon sequestration potential, and CDM projects concentrated on forestry plantation efforts. Projects linked with the initiative 20x20 followed a varied set of goals in a broader range of landscapes and was less focused on carbon sequestration.

While all projects mostly aim to intensify vegetation cover, recover biodiversity, and improve ecosystem services, restoration can take place in many forms across Latin America, which influences how much carbon a restored area will be able to trap, the study reveals.

Natural regeneration is the most prevalent choice for restoring vegetation, together with assisted regeneration and mixed plantations. FIP, GEF, and local restoration projects favored this low-cost, high-carbon sink method, highlighted the scientists. These “may contribute widely to climate change mitigation,” the study says.

Natural regeneration is a cost-effective restoration method. You don't have to invest in seedling production and plantations. On the other hand, you get what you get. In degraded lands you get pioneer species, it might take decades to get back the pre-disturbed mix of species.

Louis Verchot, Study Co-Author and Agroecosystems and Sustainable Landscapes Researcher, CIAT

The research is the most recent on the subject by Verchot and colleagues, including a paper published in the first half of this year that developed a typology of land restoration in the Caribbean and Latin America. The research classified three key restoration types, with the core defining variables being the amount of funding received, source of funding, project area under restoration, and monitoring efforts.

Drylands Out of the Restoration Spotlight

According to the research, just 25% of the restoration projects examined in Latin America focus on drylands, regardless of their exposure to desertification, food insecurity, loss of biodiversity, and climate change. Envisaging the region’s potential for more carbon-storing vegetation can aid project developers to identify which degraded drylands require restoration. Donors and funding mechanisms that back the projects have a big influence on the goals and activities, the study says.

“A diversity of projects and initiatives will contribute towards achieving the aims of the Bonn Challenge and restore large amounts of degraded land,” concluded the authors. But to be effective, the problem should be handled at its source.

Mass restoration projects first have to understand what triggers forest degradation and deforestation, as well as the social and ecological climate in which they occur, so that man handles the lands in a better manner and avoids the necessity to restore them in the future.