Nov 28 2019

A new study led by researchers from the University of Arizona reveals that nearly 40% of worldwide land plant species are classified as very rare. Such species are highly at risk of extinction due to ongoing climate change.

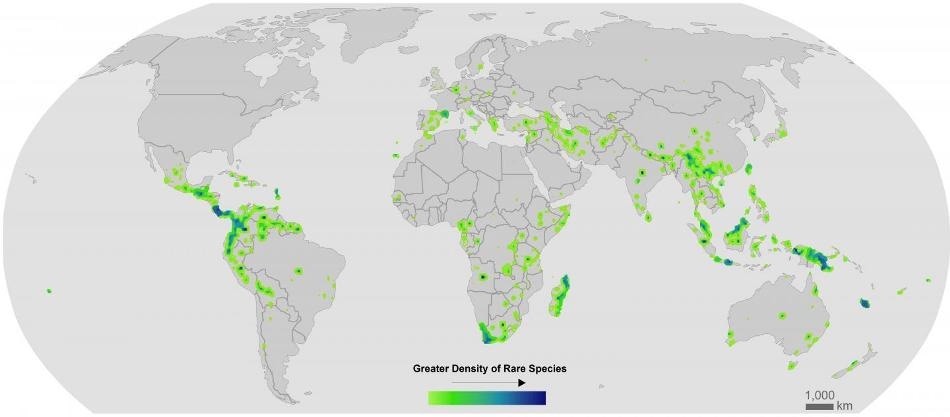

Global hotspots of rare plant species. Image Credit: Patrick R. Roehrdanz, Moore Center for Science, Conservation International Data from Enqist et al.

Global hotspots of rare plant species. Image Credit: Patrick R. Roehrdanz, Moore Center for Science, Conservation International Data from Enqist et al.

The study outcomes have been reported in a special issue of Science Advances, which coincides with the 2019 United Nations Climate Change Conference, also called COP25, in Madrid. The COP25, which will be held between 2-13 December 2019, calls nations to take measures to mitigate climate change.

When talking about global biodiversity, we had a good approximation of the total number of land plant species, but we didn’t have a real handle on how many there really are.

Brian Enquist, Study Lead Author, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona

A total of 35 scientists from institutions across the world worked for a decade to collate 20 million observational records of land plants in the world. The outcome is the largest dataset on botanical biodiversity developed for the first time. The scientists expect that this data can be useful for reducing the loss of global biodiversity by imparting strategic conservation action, including consideration of the climate change impacts.

They discovered that there are nearly 435,000 unique land plant species on Earth.

So that’s an important number to have, but it’s also just bookkeeping. What we really wanted to understand is the nature of that diversity and what will happen to this diversity in the future. Some species are found everywhere—they’re like the Starbucks of plant species. But others are very rare—think a small standalone café.

Brian Enquist, Study Lead Author, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona

Enquist and his colleagues showed that 36.5% of all land plant species are “exceedingly rare,” which implies that they have only been observed and recorded less than five times to date.

“According to ecological and evolutionary theory, we’d expect many species to be rare, but the actual observed number we found was actually pretty startling,” he remarked. “There are many more rare species than we expected.”

Furthermore, the scientists discovered that rare species likely cluster in very few hotspots, like the Northern Andes in South America, South Africa, Costa Rica, Madagascar, and Southeast Asia. They also found that such regions remained climatologically stable as the world evolved from the last ice age, enabling such rare species to survive.

Although previously these species experienced a comparatively stable climate, the likelihood of experiencing a stable future is minimal. Enquist stated that the study also showed that these extremely rare-species hotspots are predicted to experience a disproportionally high rate of human disruption and future climatic changes.

We learned that in many of these regions, there’s increasing human activity such as agriculture, cities and towns, land use and clearing. So that’s not exactly the best of news. If nothing is done, this all indicates that there will be a significant reduction in diversity—mainly in rare species—because their low numbers make them more prone to extinction.

Brian Enquist, Study Lead Author, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona

Moreover, science knows very little about such rare species.

By attempting to detect rare species, “this work is better able to highlight the dual threats of climate change and human impact on the regions that harbor much of the world’s rare plant species and emphasizes the need for strategic conservation to protect these cradles of biodiversity,” stated Patrick Roehrdanz, a co-author of the paper and managing scientist at Conservation International.

This study was conducted together with the SPARC project (Spatial Planning for Area Conservation in Response to Climate Change), which was financially supported by the Global Environment Facility and made possible by Conservation International and a National Science Foundation grant to the University of Arizona.