Jan 2 2020

Each year, water in more than half of the rivers on Earth freeze. Such frozen rivers serve as vital transportation networks for industries and communities situated at higher latitudes. Moreover, ice cover controls the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere from rivers.

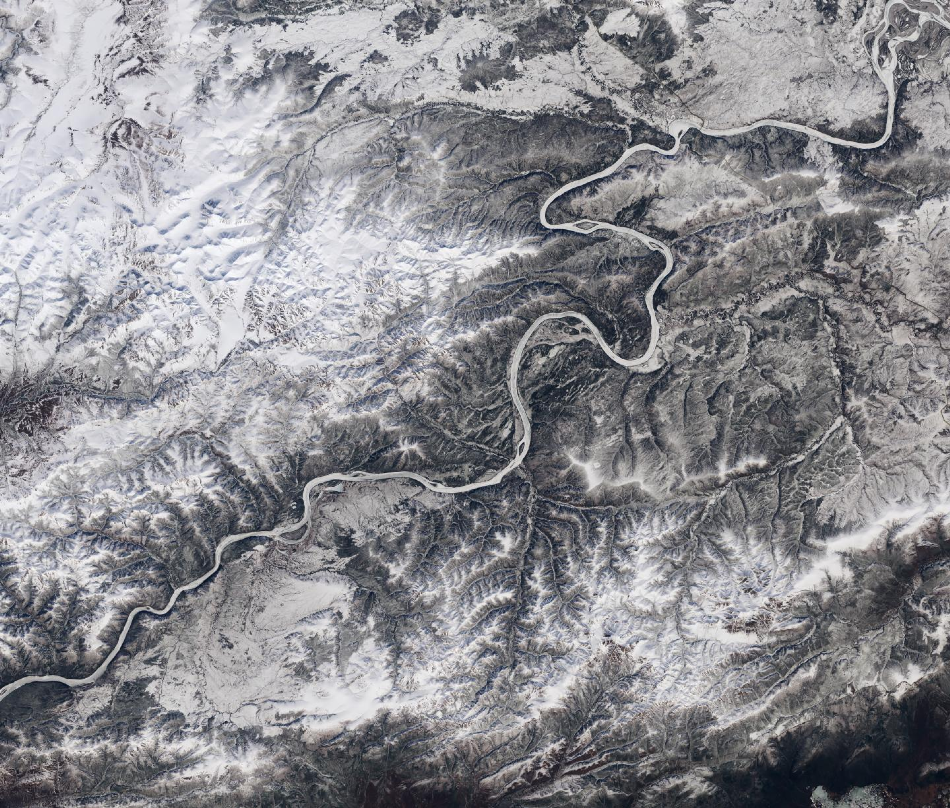

Ice cover on the Yukon River approaching its confluence with the Tanana River in Alaska. Image Credit: Landsat imagery/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and U.S. Geological Survey.

Ice cover on the Yukon River approaching its confluence with the Tanana River in Alaska. Image Credit: Landsat imagery/NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and U.S. Geological Survey.

Scientists from the Department of Geological Sciences of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have performed new research, which shows that there will be a decline in annual river ice cover by nearly six days for every 1 °C increase in global temperatures.

Such a decline will lead to environmental and economic impacts. The study titled “The past and future of global river ice,” which is the first one to analyze the future of river ice on a global scale, was reported in the Nature journal on January 1st, 2020.

We used more than 400,000 satellite images taken over 34 years to measure which rivers seasonally freeze over worldwide, which is about 56% of all large rivers. We detected widespread declines in monthly river ice coverage. And the predicted trend of future ice loss is likely to lead to economic challenges for people and industries along these rivers, and shifting seasonal patterns in greenhouse gas emissions from the ice-affected rivers.

Xiao Yang, Study Lead Author, Postdoctoral Scholar, Department of Geological Sciences, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The researchers also analyzed variations in river ice cover in the past and modeled variations that can be expected in the future. They compared river ice cover between 2008–2018 and 1984–1994 and found a monthly global decline varying from 0.3 to 4.3 percentage points. The highest declines were registered in eastern Europe, Tibetan Plateau, and Alaska.

“The observed decline in river ice is likely to continue with predicted global warming,” the paper explains.

For the future, the researchers compared predicted river ice cover between 2009–2029 and 2080–2100. The results revealed monthly declines in the Northern Hemisphere varying from 9%–15% during the winter months to 12%–68% in spring and fall. It has been predicted that the northeastern United States, the Rocky Mountains, Tibetan Plateau, and eastern Europe will be affected to a greater extent.

Ultimately, what this study shows is the power of combining massive amounts of satellite imagery with climate models to help better project how our planet will change.

Tamlin Pavelsky, Associate Professor of Global Hydrology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

George Allen, assistant professor of geography from Texas A&M University, collaborated with Xiao and Tamlin on the research work. This study was funded by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.