May 14 2020

A team of scientists has successfully produced in a laboratory setting a coral that is more resistant to increased seawater temperatures.

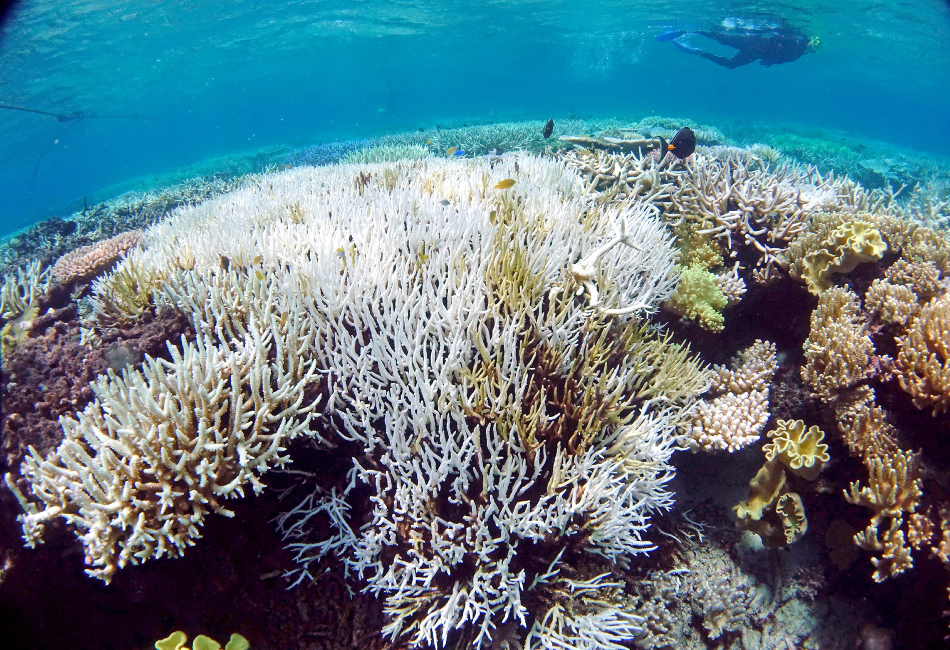

Coral bleaching. Image Credit: Chris Jones/CSIRO

Coral bleaching. Image Credit: Chris Jones/CSIRO

The team included researchers from CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and the University of Melbourne.

Corals with increased heat tolerance have the potential to reduce the impact of reef bleaching from marine heat waves, which are becoming more common under climate change.

“Coral reefs are in decline worldwide,” CSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform (SynBio FSP) science lead Dr Patrick Buerger said.

“Climate change has reduced coral cover, and surviving corals are under increasing pressure as water temperatures rise and the frequency and severity of coral bleaching events increase.”

The team made the coral more tolerant to temperature-induced bleaching by bolstering the heat tolerance of its microalgal symbionts – tiny cells of algae that live inside the coral tissue.

“Our novel approach strengthens the heat resistance of coral by manipulating its microalgae, which is a key factor in the coral’s heat tolerance,” Dr Buerger said.

The team isolated the microalgae from coral and cultured them in the specialist symbiont lab at AIMS. Using a technique called “directed evolution”, they then exposed the cultured microalgae to increasingly warmer temperatures over a period of four years.

This assisted them to adapt and survive hotter conditions.

“Once the microalgae were reintroduced into coral larvae, the newly established coral-algal symbiosis was more heat tolerant compared to the original one,” Dr Buerger said.

The microalgae were exposed to temperatures that are comparable to the ocean temperatures during current summer marine heat waves causing coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef.

The researchers then unveiled some of the mechanisms responsible for the enhanced coral bleaching tolerance.

“We found that the heat tolerant microalgae are better at photosynthesis and improve the heat response of the coral animal,” Professor Madeleine van Oppen, of AIMS and the University of Melbourne, said.

“These exciting findings show that the microalgae and the coral are in direct communication with each other. “

The next step is to further test the algal strains in adult colonies across a range of coral species.

“This breakthrough provides a promising and novel tool to increase the heat tolerance of corals and is a great win for Australian science,” SynBio FSP Director Associate Professor Claudia Vickers said.

This research was conducted by CSIRO in partnership with AIMS and the University of Melbourne. It was funded by CSIRO, Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (U.S.A.), AIMS and the University of Melbourne.