Reviewed by Alex SmithJul 18 2022

Mark Abbott expected to get a long-awaited view of the previous 160,000 years of climate change when he and his colleagues extracted a 300-foot-long core of mud from a lakebed high in the Peruvian Andes.

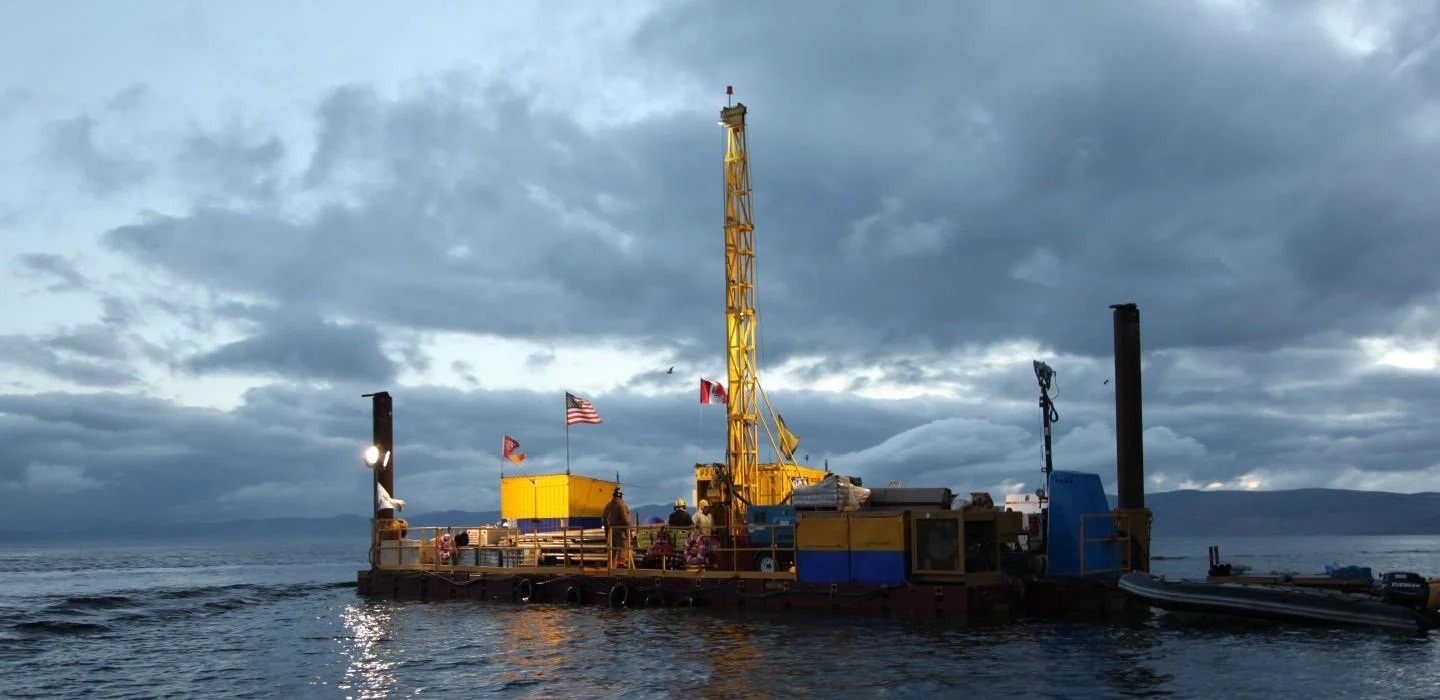

Photo of researchers working on a drill rig on Lake Junin. Image Credit: Mark Abbott

Photo of researchers working on a drill rig on Lake Junin. Image Credit: Mark Abbott

However, the lakebed preserved the ebb and flow of glaciers for more than 700,000 years, the oldest glacier record for the tropics and one of the longest records of historical climate overall, the researchers reported in the journal Nature on July 13th, 2022.

The multi-institution collaboration discovered hints about how climate change could affect the current world in that lake’s sediment.

This is unlike anything we had before. We now have a land-based record of glaciation from the tropics that is in many ways equal to our records from the ice caps at the poles and from the ocean, and that is really been lacking.

Mark Abbott, Professor, Geology and Environmental Science, Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Science, University of Pittsburgh

For many years, scientists have acknowledged that Lake Junin is a unique treasure. The lake, located in the Andes at a height of more than 13,000 feet, is ideal for archiving the changing glacial epochs since it is both far enough from the glaciers to avoid being completely covered by them since it formed and close enough to them to collect sediment and water flowing down the mountains.

The lake’s sediments are still stacked according to the year they were laid down like the pages of a history book, having escaped disruption by millennia of churning ice.

However, it took researchers more than 20 years to really access that recorded history.

Abbott, who also serves as director for the Dietrich School’s Climate and Global Change Center, stated, “It is remote, high and hard to get to. There are no boats on the lake, and it is ringed by marshes—it is a very difficult site to work on with heavy equipment, so it was a huge effort to pull this together.”

Researchers from Union College, the University of Florida, and several other academic institutions were part of the project. The paper’s co-authors, seven Pitt graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, who helped with the fieldwork and subsequent analysis, are also co-authors.

The team was able to compare the history of global climate change in a way that was not previously conceivable because of the extensive, precise record of climate change in the tropics.

The history of the glaciers preserved in the lake core was consistent with those discovered elsewhere, demonstrating an approximately 100,000-year cycle in the global distribution of ice. But it also made some interesting discoveries.

“What we have tried to do here is tie this to records in the poles and the oceans and see how they are different over time. There was a period between about 400,000 to 200,000 years ago where it looks like the tropics are wetter than the poles”, added Abbott.

The 300-foot-long core had to be divided into thousands of pieces, and the sediment layers had to be meticulously removed and studied in order to read the record. Each action that forms a layer leaves its own unique mark, whether it was glaciers pounding against rocks or a lake drying up to become a wetland.

Researchers were able to determine how temperature and precipitation altered throughout time by analyzing the geochemical and magnetic characteristics of the sediment.

To ascertain the time each layer was deposited, the researchers also utilized a variety of techniques, including radiocarbon dating, which was carried out by Pitt geology and environmental science Ph.D. student Arielle Woods.

Patterns that could provide hints as to what to expect as the world warms in the 21st century were discovered while comparing the 700,000 years of climatic change from Lake Junin with those found elsewhere in the world.

Abbott further stated, “When the Arctic warmed, the southern tropics dried out dramatically. You shift heat into the southern hemisphere, and the monsoon weakens, effectively, so you get very dry conditions.”

That is particularly significant given how many people depend on the consistency of the monsoons to cultivate their crops. And it adds additional support to a theory that anybody who studies the climate of the world is acquainted with.

“The global climate is very connected. If you change something anywhere on the globe, you see its effects virtually everywhere,” concluded Abbott.

Journal Reference:

Rodbell, D. T., et al. (2022) 700,000 years of tropical Andean glaciation. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04873-0.