Jul 8 2014

A decade of research by Rice University scientists has produced a two-dimensional model to prove how gas hydrate, the “ice that burns,” is formed under the ocean floor.

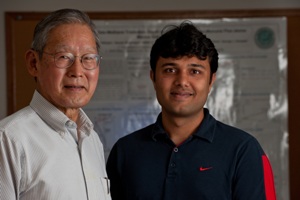

Rice University chemical engineer George Hirasaki, left, and alumnus Sayantan Chatterjee led a project to build a two-dimensional mathematical model to help identify rich pockets of gas hydrate under the ocean floor. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Rice University chemical engineer George Hirasaki, left, and alumnus Sayantan Chatterjee led a project to build a two-dimensional mathematical model to help identify rich pockets of gas hydrate under the ocean floor. (Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Gas hydrate — basically methane frozen under high pressures and low temperatures — has potential as a source of abundant energy, if it can be extracted and turned into usable form.

It also has potential to do great harm, if global warming results in melting hydrate that releases methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

The award-winning mathematical model created by Rice alumnus Sayantan Chatterjee, who earned his doctorate in chemical engineer George Hirasaki’s group, is intended to help pinpoint abundant pockets of hydrate by extrapolating data from several sources: one-dimensional core samples, seismic surveys that image the fractures as well as stratified layers of sand and clay that build up over millennia, and the geochemistry of sediment and water near the ocean floor, which offers chemical clues to what lies beneath.

The research was published by the Journal of Geophysical Research – Solid Earth.

There’s a lot at stake for energy producers — and consumers — in finding hydrates in high concentrations, with as much as 20 trillion tons of methane under the sea. Japanese researchers are already testing production techniques in the Pacific, but extraction without reliable exploration tools is too expensive, Chatterjee said.

The Rice researchers’ two-dimensional model draws upon a variety of survey techniques to envision a more accurate slice of the deep-sea formation.

“Our modeling incorporates geologic processes like sedimentation and compaction that enable methane-rich fluids to flow through porous media,” Chatterjee said. Methane degraded by microbes from organic matter or rising from the depths turns into hydrate when it encounters the necessary pressure, temperature and salinity conditions in the gas hydrate stability zone, which can be as shallow as a few hundred meters.

“High-saturation hydrate deposits preferentially occur in fracture networks within fine-grained sediment and interbedded, permeable sand sequences, and we’re looking for such lithologic sweet spots,” he said.

Chatterjee explained the complex stratigraphy and lack of homogeneity of subsea formations limits the ability of one-dimensional modeling and core samples to scan a potential hydrate reservoir isolated in permeable sand sequences between dense layers of clay. “Marine lithologic layering is very complex, and we can’t replicate it in our models. But we have developed techniques to compute local fluid flow in lithologically complex reservoirs, which we correlate to local hydrate saturation,” he said.

“When people seismically image the submarine formations and recover sediment cores dominated with faults and fractures, they find these fractures to be filled with hydrates,” Chatterjee said. “Our model has explained this observation. It shows that these fracture networks and sand layers are the sweet spots for hydrate occurrence, the ones we want to pinpoint when it comes to exploration.”

The Rice team intends the model to locate these hydrate-rich pockets and estimate how saturated they’re likely to be based on the geologic setting and history. “Only when a pore space is highly saturated with hydrate is it economically feasible to drill at that location to extract these trapped hydrocarbons,” he said. “But first we have to estimate the fluid flow. No flow, no hydrates.”

Chatterjee presented his research at the seventh International Conference on Gas Hydrates in Edinburgh, Scotland, and won first prize at the prestigious Society of Petroleum Engineers’ Young Professionals meeting and second prize at the Gulf Coast Regional student paper competition.

Co-authors are Rice alumnus Gaurav Bhatnagar, now a scientist at Shell International Exploration and Production in Houston; Brandon Dugan, an associate professor of Earth science; Gerald Dickens, a professor of Earth science; and Walter Chapman, the William W. Akers Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, all of Rice. Chatterjee is a scientist at Shell Global Solutions in Houston. Hirasaki is the A.J. Hartsook Professor Emeritus of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

The Department of Energy, Rice’s Shell Center for Sustainability and Rice’s Consortium of Processes in Porous Media supported the research.