Dec 16 2007

Carbon emissions from human activities are not just heating up the globe, they are changing the ocean’s chemistry. This could soon be fatal to coral reefs, which are havens for marine biodiversity and underpin the economies of many coastal communities. Scientists from the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology have calculated that if current carbon dioxide emission trends continue, by mid-century 98% of present-day reef habitats will be bathed in water too acidic for reef growth. Among the first victims will be Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest organic structure.

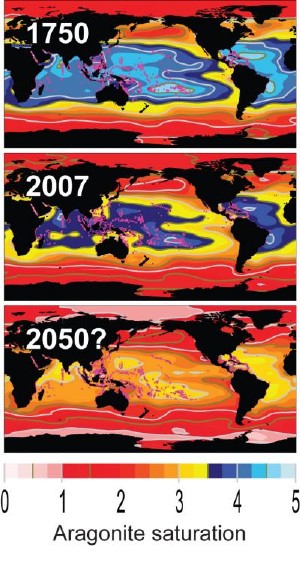

In year 1750, over 98 percent of coral reefs (magenta dots) grew in optimal conditions with aragonite saturation greater than 3.5 (blue colors). Such water is rapidly disappearing and will be gone in several decades if current carbon dioxide emission trends continue. Atmospheric CO2 levels are 280 ppm, 380 ppm, and 550 ppm for years 1750, 2007, and 2050, respectively.

In year 1750, over 98 percent of coral reefs (magenta dots) grew in optimal conditions with aragonite saturation greater than 3.5 (blue colors). Such water is rapidly disappearing and will be gone in several decades if current carbon dioxide emission trends continue. Atmospheric CO2 levels are 280 ppm, 380 ppm, and 550 ppm for years 1750, 2007, and 2050, respectively.

Chemical oceanographers Ken Caldeira and Long Cao are presenting their results in a multi-author paper in the December 14 issue of Science* and at the annual meeting of American Geophysical Union in San Francisco on the same date. The work is based on computer simulations of ocean chemistry under levels of atmospheric CO2 ranging from 280 parts per million (pre-industrial levels) to 5000 ppm. Present levels are 380 ppm and rapidly rising due to accelerating emissions from human activities, primarily the burning of fossil fuels.

“About a third of the carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere is absorbed by the oceans,” says Caldeira, “which helps slow greenhouse warming, but is a major pollutant of the oceans.” The absorbed CO2 produces carbonic acid, the same acid that gives soft drinks their fizz, making certain minerals called carbonate minerals dissolve more readily in seawater. This is especially true for aragonite, the mineral used by corals and many other marine organisms to grow their skeletons.

“Before the industrial revolution, over 98% of warm water coral reefs were bathed with open ocean waters 3.5 times supersaturated with aragonite, meaning that corals could easily extract it to build reefs,” says Cao. “But if atmospheric CO2 stabilizes at 550 ppm -- and even that would take concerted international effort to achieve -- no existing coral reef will remain in such an environment.” The chemical changes will impact some regions sooner than others. At greatest risk are the Great Barrier Reef and the Caribbean Sea.

Carbon dioxide’s chemical effects on the ocean are largely independent of its effects on climate, so measures to mitigate warming short of reducing emissions will be of little help in slowing acidification, the researchers say. In fact, impending chemical changes may require emissions cuts even more drastic than those for climate alone.

“These changes come at a time when reefs are already stressed by climate change, overfishing, and other types of pollution,” says Caldeira, “so unless we take action soon there is a very real possibility that coral reefs — and everything that depends on them —will not survive this century.”