Aug 27 2014

New questions about geology, oceanography and seafloor ecosystems are being raised because of research by a Mississippi State University geologist.

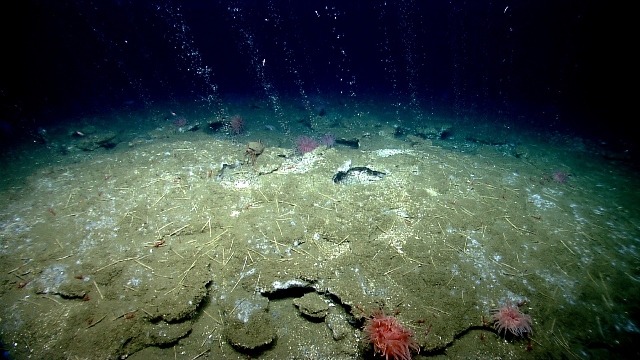

Ocean floor methane seeps. (Courtesy of NOAA)

Ocean floor methane seeps. (Courtesy of NOAA)

Lead author Adam Skarke, assistant professor of geosciences at MSU, worked with researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and other institutions on a scientific team that discovered methane seeps in unlikely places along the seafloor on the northern part of the U.S. Atlantic margin.

The group’s scientific paper, “Widespread methane leakage from the sea floor on the northern U.S. Atlantic margin,” was published online Sunday [Aug. 24] by the peer-reviewed journal Nature Geoscience.

Before he joined the faculty at MSU, Skarke worked as a physical scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (OER). As part of a large team of scientists and technicians, Skarke participated in many cruises on the NOAA ship Okeanos Explorer as it mapped the Atlantic Ocean floor between North Carolina and Cape Cod. The discovery of gas plumes in the water column over the seafloor, detailed in the new publication, used data the ship collected starting in 2011, Skarke said.

He and his colleagues found 570 methane seeps in this area, compared to only three formerly known sites.

To analyze the NOAA OER data and locate the positions of the plumes, which correspond to places where methane gas is seeping out of the seafloor, Skarke worked closely with Brown University undergraduate and NOAA Hollings Scholar Mali’o Kodis during the summer of 2013.

Methane often naturally leaks from the seafloor, particularly in petroleum basins like the Gulf of Mexico or on tectonically active continental margins like the U.S. Pacific Coast, Skarke said. However, the geologic characteristics of the U.S. Atlantic margin suggest the seepage was not necessarily expected there because the tectonically passive area lacks an underlying petroleum basin.

The team thinks that many of the newly-discovered seeps may be related to the breakdown of a special kind of “methane ice” or gas hydrate, a frozen combination of methane and water stable in sediments below 500 or more meters, or 1,640 feet, of ocean water, Skarke said. With small changes in ocean temperature, gas hydrate can release its methane into the sediments, and the gas may escape at the seafloor to form plumes in the water column.

“Globally, the upper ocean has been warming for decades,” Skarke said. “Some of the seeps we found are similar to those on Arctic Ocean margins, where warming has been more rapid. But we also know that some subsets of the seeps have probably been active for over 1,000 years. A key question is how the long-term seepage and short-term warming of the ocean are related to methane escape.”

Skarke said the research “does not provide sufficient evidence to draw objective conclusions about the relationship between these methane seeps and global climate change.”

“This significant discovery instead introduces a number of related questions that require further exploration and investigation to address,” he added.

Although methane, or natural gas, is used as an energy source worldwide, the type of methane leaking at most of the seep sites is probably produced by micro-organisms digesting organic matter in the shallow sediments, he said. At this time, no evidence suggests the seeps tap into deep natural gas reservoirs that can be used for energy. Once samples of the methane are obtained, simple measurements made by geochemists can determine if shallow or deep gas sources feed the seeps.

Methane is a strong greenhouse gas, but nearly all of the seeps described in the new study leak at such deep ocean depths that methane does not reach the atmosphere directly, he emphasized. Instead, micro-organisms in the water column transform most of the methane into carbon dioxide, making ocean waters more acidic, which can harm some types of marine life.

The methane seeps provide new natural laboratories for ecologists who study life on the deep ocean floor, Skarke said. Animals there use the energy created by chemical reactions to survive—chemosynthetic life-forms. For example, their metabolisms may depend on methane or hydrogen sulfide, a common seep gas toxic to many life forms.

“These newly-discovered seeps have expanded the number of locations that deep sea ecologists can study,” Skarke said. “The NOAA OER program used its remotely operated vehicle to visit about 1 percent of the seeps in 2013, and it found well-developed communities of chemosynthetic mussels thriving near the methane plumes. Two years ago, no human had ever seen these seafloor communities that have now been found at the seep sites.”

He said additional research questions for deep sea ecologists include determining how separate seeps are colonized with new life, as well as understanding the structure of the communities and the relationships among bacteria, small fauna, and larger organisms, like mussels.

“A cornerstone of the NOAA OER program is the collection of data that can lead to new discoveries for the scientific community,” he said. “One unique aspect of the program that made it so enjoyable to work there was the fact that we collected many types of data about U.S. oceans and made the data immediately available to the scientific community for studies that could not otherwise have been completed.”

Skarke said he appreciates the support of MSU administrators, especially those in the Department of Geosciences, as he and his collaborators readied the research for publication in a top-tier, peer-reviewed journal. In addition to Skarke and Kodis, authors of the paper include Carolyn Ruppel of the USGS Gas Hydrates Project, Daniel Brothers of USGS and Elizabeth Lobecker of Earth Resources Technology.

Visit dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2232 to view the complete abstract of “Widespread methane leakage from the sea floor on the northern U.S. Atlantic margin,” or go to http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=3979&from=rss_home#.U_tMVGP_mzd to read USGS’ press release about the research.

Learn more about Skarke at geosciences.msstate.edu/people/skarke/index.htm.

MSU is online at www.msstate.edu, facebook.com/msstate, instagram.com/msstate and twitter.com/msstate.