Jun 18 2015

UC Irvine / NASA UC Irvine researchers used NASA satellites to show aquifer depletion worldwide. They are trying to raise awareness about the lack of information about remaining groundwater supplies on Earth

UC Irvine / NASA UC Irvine researchers used NASA satellites to show aquifer depletion worldwide. They are trying to raise awareness about the lack of information about remaining groundwater supplies on Earth

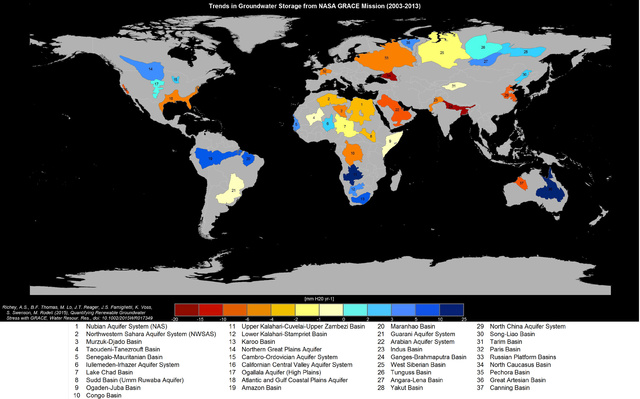

UC Irvine researchers conducted two new studies using data from the NASA Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment satellites and reported rapid draining of water in some of the large groundwater basins worldwide due to human consumption. Further, there is less or no data available on the remaining amount of water in these basins.

The findings suggested that groundwater is being rapidly emptied by the significant percentage of Earth’s population without any knowledge on when water might get exhausted. The results were published in Water Resources Research.

Available physical and chemical measurements are simply insufficient. Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left.

Jay Famiglietti

Senior Water Scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

For the first time, the researchers investigated the groundwater losses based on the available space data through readings created by NASA’s twin GRACE satellites. These satellites measure the bumps and dips in the gravity of the Earth, which is influenced by the weight of water.

In the first paper, 37 largest aquifers of the Earth were studied for the period between 2003 and 2013. The eight worst off were categorized as overstressed, with almost no natural replenishment to offset usage. Another five aquifers observed in descending order were found to be highly/extremely stressed based on their replenishment level, with some amount of flow back watler.

The driest regions across the world are the most overburdened as they take up large amount of underground water. The findings suggested that the population growth and climate change are two likely parameters that further strengthen the issue.

What happens when a highly stressed aquifer is located in a region with socioeconomic or political tensions that can’t supplement declining water supplies fast enough?

We’re trying to raise red flags now to pinpoint where active management today could protect future lives and livelihoods.

Alexandra Richey

Doctural Student - UCI

The team found that the most overstressed groundwater basins in the world is the Arabian Aquifer System which supplies water to over 60 million people. The second-most overstressed is the Indus Basin aquifer of northwestern India and Pakistan, and third is the Murzuk-Djado Basin in northern Africa. Although the Central Valley in California is mainly used for agriculture suffers rapid depletion, it was rated slightly better off in the study yet labeled extremely stressed.

“As we’re seeing in California right now, we rely much more heavily on groundwater during drought. When examining the sustainability of a region’s water resources, we absolutely must account for that dependence,” Famiglietti said.

In the second paper, the researchers concluded that the total amount of the world’s usable groundwater left over in the basins is less known, as the estimates often vary abruptly. However, the estimates are expected to be far less than rudimentary estimates reported decades ago.

With the comparison of the satellite-derived groundwater loss rates to the available data on groundwater availability, major discrepancies were found in the projected “time to depletion". For example, in the overstressed Northwest Sahara Aquifer System, the estimates varied between 10 and 21,000 years.

“We don’t actually know how much is stored in each of these aquifers. Estimates of remaining storage might vary from decades to millennia. In a water-scarce society, we can no longer tolerate this level of uncertainty, especially since groundwater is disappearing so rapidly,” Richey said.

The research also reports significant ecological damage such as subsiding land, declining water quality and depleted rivers due to the groundwater scarcity.

Groundwater aquifers are usually found deep inside the rock layers below Earth’s surface or soil. The thickness and depth of aquifers make it hard to drill. Otherwise, it is possible to study how deep the moisture prevails by reaching the bedrock.

The research team includes co-authors from NASA, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, National Taiwan University and UC Santa Barbara.