Jul 13 2015

A new NASA study of ocean temperature measurements shows in recent years extra heat from greenhouse gases has been trapped in the waters of the Pacific and Indian oceans.

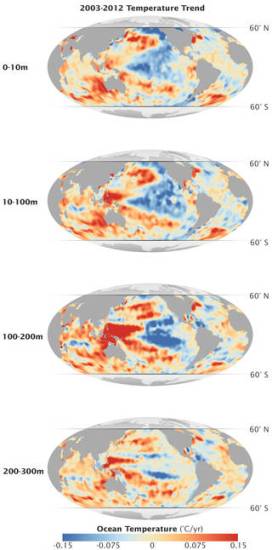

Temperature data from the global ocean (2003-2012) at four depths shows the warmest water at depths of about 330-660 feet (third panel from top) in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans. Credits: NASA Earth Observatory

Temperature data from the global ocean (2003-2012) at four depths shows the warmest water at depths of about 330-660 feet (third panel from top) in the western Pacific and Indian Oceans. Credits: NASA Earth Observatory

Researchers say this shifting pattern of ocean heat accounts for the slowdown in the global surface temperature trend observed during the past decade.

Researchers Veronica Nieves, Josh Willis and Bill Patzert of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, California, found a specific layer of the Indian and Pacific oceans between 300 and 1,000 feet (100 and 300 meters) below the surface has been accumulating more heat than previously recognized. They also found the movement of warm water has affected surface temperatures. The result was published Thursday in the journal Science.

During the 20th century, as greenhouse gas concentrations increased and trapped more heat energy on Earth, global surface temperatures also increased. However, in the 21st century, this pattern seemed to change temporarily.

"Greenhouse gases continued to trap extra heat, but for about 10 years starting in the early 2000s, global average surface temperature stopped climbing, and even cooled a bit," said Willis.

In the study, researchers analyzed direct ocean temperature measurements, including observations from a global network of about 3,500 ocean temperature probes known as the Argo array. These measurements show temperatures below the surface have been increasing.

The Pacific Ocean is the primary source of the subsurface warm water found in the study, though some of that water now has been pushed to the Indian Ocean. Since 2003, unusually strong trade winds and other climatic features have been piling up warm water in the upper 1,000 feet of the western Pacific, pinning it against Asia and Australia.

"The western Pacific got so warm that some of the warm water is leaking into the Indian Ocean through the Indonesian archipelago," said Nieves, the lead author of the study.

The movement of the warm Pacific water westward pulled heat away from the surface waters of the central and eastern Pacific, which resulted in unusually cool surface temperatures during the last decade. Because the air temperature over the ocean is closely related to the ocean temperature, this provides a plausible explanation for the global cooling trend in surface temperature.

Cooler surface temperatures also are related to a long-lived climatic pattern called the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which moves in a 20 to 30 year cycle. It has been in a cool phase during the entire time surface temperatures showed cooling, bringing cooler-than-normal water to the eastern Pacific and warmer water to the western side. There currently are signs the pattern may be changing to the opposite phase, with observations showing warmer-than-usual water in the eastern Pacific.

"Given the fact the Pacific Decadal Oscillation seems to be shifting to a warm phase, ocean heating in the Pacific will definitely drive a major surge in global surface warming," Nieves said.

Previous attempts to explain the global surface temperature cooling trend have relied more heavily on climate model results or a combination of modeling and observations, which may be better at simulating long-term impacts over many decades and centuries. This study relied on observations, which are better for showing shorter-term changes over 10 to 20 years. In shorter time spans, natural variations such as the recent slowdown in global surface temperature trends can have larger regional impacts on climate than human-caused warming.

Pauses of a decade or more in Earth's average surface temperature warming have happened before in modern times, with one occurring between the mid-1940s and late 1970s.

"In the long term, there is robust evidence of unabated global warming," Nieves said.

NASA uses the vantage point of space to increase our understanding of our home planet, improve lives and safeguard our future. NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth's interconnected natural systems with long-term data records. The agency freely shares this unique knowledge and works with institutions around the world to gain new insights into how our planet is changing.