Jul 27 2015

New research using NASA satellite data and ocean biology models suggests tiny organisms in vast stretches of the Southern Ocean play a significant role in generating brighter clouds overhead. Brighter clouds reflect more sunlight back into space affecting the amount of solar energy that reaches Earth's surface, which in turn has implications for global climate. The results were published July 17 in the journal Science Advances.

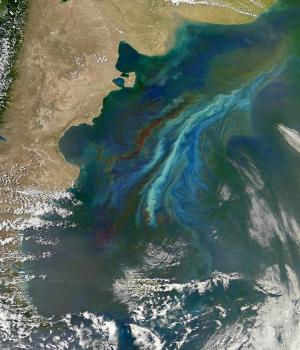

Satellites use chlorophyll's green color to detect biological activity in the oceans. The lighter-green swirls are a massive December 2010 plankton bloom following ocean currents off Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America.

Satellites use chlorophyll's green color to detect biological activity in the oceans. The lighter-green swirls are a massive December 2010 plankton bloom following ocean currents off Patagonia, at the southern tip of South America.

The study shows that plankton, the tiny drifting organisms in the sea, produce airborne gases and organic matter to seed cloud droplets, which lead to brighter clouds that reflect more sunlight.

"The clouds over the Southern Ocean reflect significantly more sunlight in the summertime than they would without these huge plankton blooms," said co-lead author Daniel McCoy, a University of Washington doctoral student in atmospheric sciences. "In the summer, we get about double the concentration of cloud droplets as we would if it were a biologically dead ocean."

Although remote, the oceans in the study area between 35 and 55 degrees south is an important region for Earth's climate. Results of the study show that averaged over a year, the increased brightness reflects about 4 watts of solar energy per square meter.

McCoy and co-author Daniel Grosvenor, now at the University of Leeds, began this research in 2014 looking at NASA satellite data for clouds over the parts of the Southern Ocean that are not covered in sea ice and have year-round satellite data. The space agency launched the first Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), instrument onboard the Terra satellite in 1999 to measure the cloud droplet size for all Earth's skies. A second MODIS instrument was launched onboard the Aqua satellite in 2002.

Clouds reflect sunlight based on both the amount of liquid suspended in the cloud and the size of the drops, which range from tiny mist spanning less than a hundredth of an inch (0.1 millimeters) to large drops about half an inch (10 millimeters) across. Each droplet begins by growing on an aerosol particle, and the same amount of liquid spread across more droplets will reflect more sunlight.

Using the NASA satellite data, the team showed in 2014 that Southern Ocean clouds are composed of smaller droplets in the summertime. But that doesn't make sense, since the stormy seas calm down in summer and generate less sea spray to create airborne salts.

The new study looked more closely at what else might be making the clouds more reflective. Co-lead author Susannah Burrows, a scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Lab in Richland, Washington, used an ocean biology model to see whether biological matter could be responsible.

Marine life can affect clouds in two ways. The first is by emitting a gas, such as dimethyl sulfide released by Sulfitobacter bacteria and phytoplankton such as coccolithophores, which creates the distinctive sulfurous smell of the sea and also produces particles to seed marine cloud droplets.

The second way is directly through organic matter that collects at the water's surface, forming a bubbly scum that can get whipped up and lofted into the air as tiny particles of dead plant and animal material.

By matching the cloud droplet concentration with ocean biology models, the team found correlations with the sulfate aerosols, which in that region come mainly from phytoplankton, and with the amount of organic matter in the sea spray.

"The dimethyl sulfide produced by the phytoplankton gets transported up into higher levels of the atmosphere and then gets chemically transformed and produces aerosols further downwind, and that tends to happen more in the northern part of the domain we studied," Burrows said. "In the southern part of the domain there is more effect from the organics, because that's where the big phytoplankton blooms happen."

Taken together, these two mechanisms roughly double the droplet concentration in summer months.

The Southern Ocean is a unique environment for studying clouds. Unlike in other places, the effects of marine life there are not swamped out by aerosols from forests or pollution. The authors say it is likely that similar processes could occur in the Northern Hemisphere, but they would be harder to measure and may have a smaller effect since aerosol particles from other sources are so plentiful.