Jul 28 2016

Electric cars with significantly smaller, lighter and less expensive batteries could be on the horizon if a new national research effort achieves its ambitious goal of significantly improving upon the batteries that power today's electric vehicles.

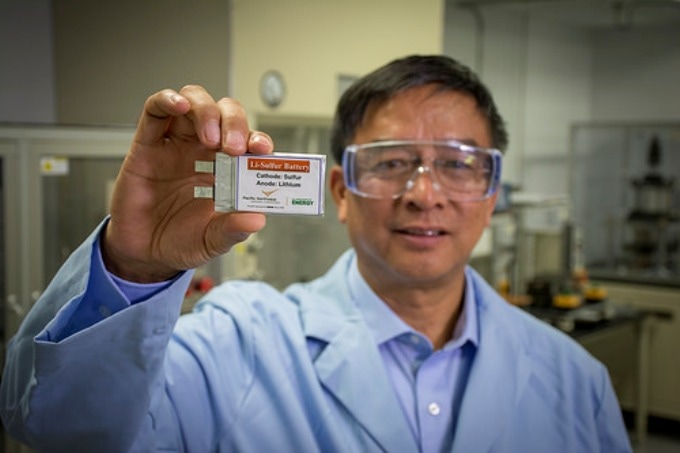

The PNNL-led Battery500 consortium aims to significantly improve upon the batteries that power today's electric vehicles by almost tripling the specific energy in lithium batteries. Pictured here is PNNL researcher Jason Zhang, who will co-lead the consortium's group focused on improving electrodes and electrolytes.(Credit: PNNL)

The PNNL-led Battery500 consortium aims to significantly improve upon the batteries that power today's electric vehicles by almost tripling the specific energy in lithium batteries. Pictured here is PNNL researcher Jason Zhang, who will co-lead the consortium's group focused on improving electrodes and electrolytes.(Credit: PNNL)

Led by Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, the Battery500 consortium will receive up to $10 million a year over five years from the Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, the White House has announced. The multi-disciplinary consortium includes leaders from DOE national labs, universities and industry, all of which are working together to make smaller, lighter and less expensive batteries that can be adopted by manufacturers.

"Our goal is to extract every available drop of energy from battery materials while also producing a high-performance battery that is reliable, safe and less expensive," said consortium director and PNNL materials scientist Jun Liu. "Through our multi-institutional partnership, which includes some of the world's most innovative energy storage leaders, the Battery500 consortium will examine the best options to create the most powerful next-generation lithium batteries for electric cars."

Beyond PNNL, the consortium includes the following partners:

- Brookhaven National Laboratory

- Idaho National Laboratory

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

- Binghamton University (State University of New York)

- Stanford University

- University of California, San Diego

- University of Texas at Austin

- University of Washington

- IBM (advisory board member)

Battery500's aggressive goal is to develop lithium-metal batteries that have almost triple the "specific energy" found in the batteries that power today's electric cars. Specific energy measures the amount of energy packed into a battery based on its weight. Because electric vehicles (EVs) need to be lightweight to drive farther on the same charge, EV batteries with high specific energies are essential.

The consortium aims to build a battery pack with a specific energy of 500 watt-hours per kilogram, compared to the 170-200 watt-hours per kilogram in today's typical EV battery. Achieving this goal would result in a smaller, lighter and less expensive battery.

The team hopes to reach these goals by focusing on lithium-metal batteries, which use lithium instead of graphite for the battery's negative electrode. The team will pair lithium with two different materials for the battery's positive electrode. While studying these materials, the consortium will prevent unwanted side reactions in the whole battery that weaken a battery's performance.

A key focus of the consortium is to ensure the technological solutions it develops meet the needs of automotive and battery manufacturers. Consortium members will work to ensure significant innovations can be quickly and seamlessly implemented by industry throughout the project.

Recognizing diversity in experience and opinions often results in better solutions, the consortium will also welcome ideas from others. The team will set aside 20 percent of its overall budget for "seedling projects," or work based on proposals from throughout the battery research community.

Though the immediate goal is to make effective, affordable batteries for EVs, Liu expects the consortium's work could also advance stationary grid energy storage.

Battery500 is also expected to take advantage of DOE facilities, including the fabrication equipment at PNNL's Advanced Battery Facility and materials characterization instruments at EMSL, the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE Office of Science User Facility on PNNL's campus. PNNL's lead role in the consortium builds on its decades of leadership in materials science, chemistry, transportation and power grid modernization.