Oct 23 2017

For over a century, researchers have been intrigued and thrilled by biochar, a carbon-rich, charcoal-like material derived from oxygen-deprived plant or similar organic matter. When used as a soil additive, biochar has the ability to store carbon and thereby decrease release of greenhouse gas. It can also slowly release nutrients, thus functioning as a non-toxic fertilizer.

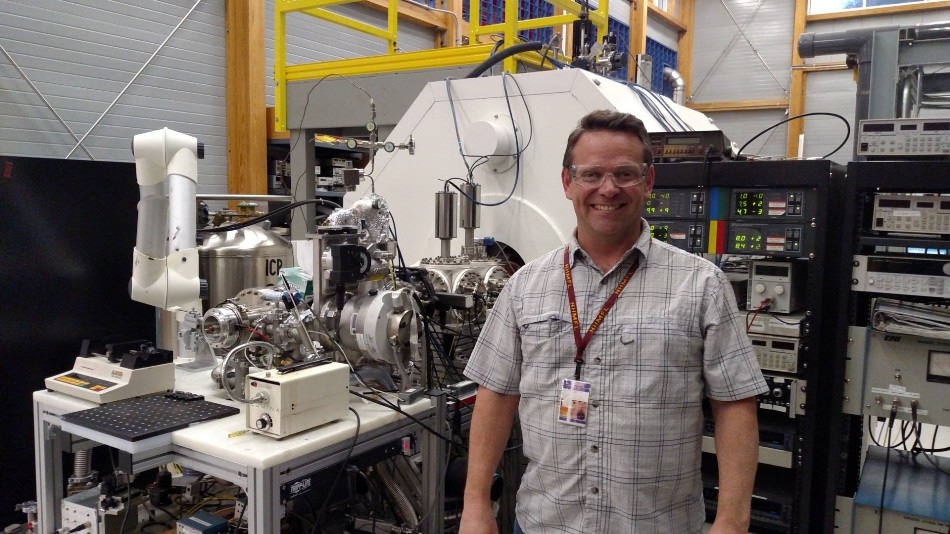

Research scientist Robert Young with the mass spectrometer at Florida State University’s MagLab. This instrument helped the CSU scientists identify elemental signatures in a biochar carbon coating. Credit: Colorado State University

Research scientist Robert Young with the mass spectrometer at Florida State University’s MagLab. This instrument helped the CSU scientists identify elemental signatures in a biochar carbon coating. Credit: Colorado State University

However, the exact chemistry behind biochar’s ability to store nutrients and advance plant growth has been a puzzle to date, thereby considerably restricting its commercial application.

At present, an international research team—mainly constituting experts from Colorado State University—has shone light on remarkable detail and mechanistic knowledge of biochar’s ostensibly amazing characteristics. The study, published in the Nature Communications journal on October 20, 2017, was headed by Germany’s University of Tuebingen, and has shown that when biochar is composted, a very thin organic coating is formed, which considerably enhances the fertilizing potential of biochar. A mix of cutting-edge analytical methods were used to validate that the coating enhances the strength of the interactions of biochar with water and also its potential to store soil nitrates and similar nutrients.

Such an in-depth knowledge of the characteristics of biochar could have the potential to start a vast commercialization of biochar fertilizers. This change may lead to worldwide reliance on inorganic nitrogen fertilizers that have functioned as the state-of-the-art food-production means for nearly 100 years.

CSU contribution

The international research team included Thomas Borch, professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at CSU with joint appointments in chemistry and civil and environmental engineering, and Robert Young, a research scientist. The CSU researchers were instrumental in performing high-resolution mass spectrometry at Florida State University’s National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. The data extracted by them assisted in validating the composition of the biochar’s nanoscale carbon coating.

To characterize a super-thin carbon coating on a carbon substrate is nearly impossible, our international team used many different advanced techniques to perform the analyses. Robert Young led our group’s contribution of ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry to investigate the coating and probe its elemental makeup.

Thomas Borch, professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences at CSU

Composted biochar

Andreas Kappler, from the Center for Applied Geoscience at the University of Tuebingen, and Nikolas Hagemann, a geo-ecologist, headed the study. The researchers intended to test biochar before and after composting it using mixed manure. They used a combination of spectroscopic and microscopic investigations and discovered that dissolved organic substances had a major role in biochar composting and formed the thin organic coating.

“This organic coating makes the difference between fresh and composted biochar,” stated Kappler. “The coating improves the biochar’s properties of storing nutrients and forming further organic soil substances.” Hagemann further stated that the coating was formed when untreated biochar was mixed with soil, however this was very gradually. Commercial composting experiments were performed on a small scale by adopting expertise and infrastructure from the Ithaka Institute in Switzerland.

Why biochar?

Imprudent application of liquid manure or mineral nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture has severe influence on the environment. These fertilizers lead to the release of nitrous oxide, culminating in the leaching of nitrates into the groundwater. Researchers have proposed the addition of biochar as a nutrient carrier to the soil as an environment-friendly substitute. However, the widespread use of biochar has not been economically feasible due to the lack of knowledge on the way it stores and emits nitrates.

“In agricultural crop production, higher yields usually only occur when biochar is applied together with nutrients from non-charred biomass such as liquid manure,” stated Hagemann. “Using biochar without adding nutrients or with pure mineral nutrients has proved to be far less successful in many experiments.”

The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (Berlin) supported the study in the form of a doctorate scholarship for Nikolas Hagemann. The EU COST Initiative TD1104 and the Ithaka Institute (Switzerland) also supported the research.