Aug 24 2018

Human lives are shortened by more than a year due to air pollution, according to a new research from a team of top environmental engineers and public health researchers. Improved air quality could result in a substantial extension of lifespans globally.

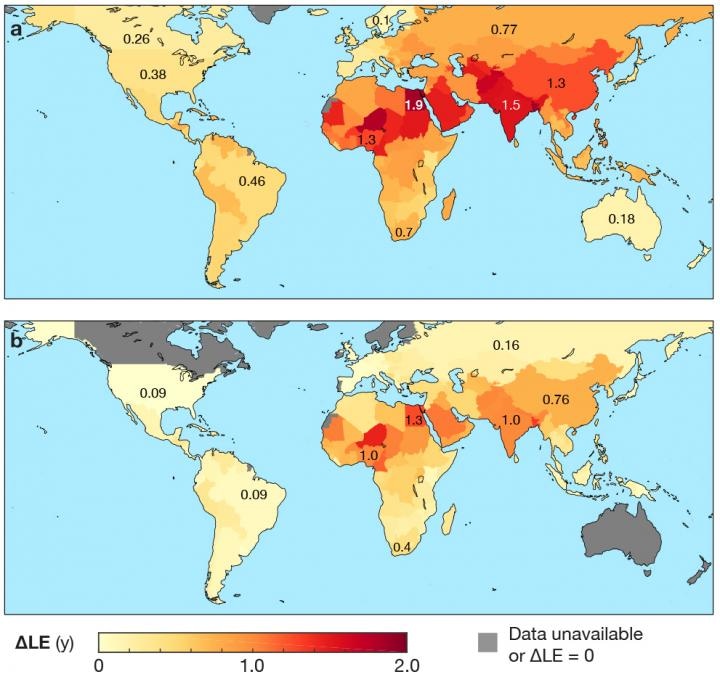

Upper panel a: How air pollution shortens human life expectancy around the world. Lower panel b: Gains in life expectancy that could be reached by meeting World Health Organization guidelines for air quality around the world. (Image credit: Cockrell School of Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin)

Upper panel a: How air pollution shortens human life expectancy around the world. Lower panel b: Gains in life expectancy that could be reached by meeting World Health Organization guidelines for air quality around the world. (Image credit: Cockrell School of Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin)

This is the first time that data on air pollution and life expectancy has been explored together so as to examine the universal variations in how they impact overall life expectancy.

The scientists studied outdoor air pollution from particulate matter (PM) smaller than 2.5 µm. These minute particles can go deep into the lungs, and breathing PM2.5 is related to increased risk of heart attacks, respiratory diseases, strokes, and cancer. PM2.5 pollution comes from fires, power plants, cars and trucks, agriculture, and industrial emissions.

Headed by Joshua Apte in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin, the team used data from the Global Burden of Disease Study to calculate PM2.5 air pollution exposure and its repercussions in 185 countries. They then quantified the national impact on lifespan for every country as well as on a worldwide scale.

The results were reported in the August 22nd issue of the Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

"The fact that fine particle air pollution is a major global killer is already well known," said Apte, who is an assistant professor in the Cockrell School's Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering and in the Dell Medical School's Department of Population Health. "And we all care about how long we live. Here, we were able to systematically identify how air pollution also substantially shortens lives around the world. What we found is that air pollution has a very large effect on survival - on average about a year globally."

In the background of other important phenomena negatively impacting human survival rates, Apte said this is a large number.

"For example, it's considerably larger than the benefit in survival we might see if we found cures for both lung and breast cancer combined," he said. "In countries like India and China, the benefit for elderly people of improving air quality would be especially large. For much of Asia, if air pollution were removed as a risk for death, 60-year-olds would have a 15 percent to 20 percent higher chance of living to age 85 or older."

Apte believes this discovery is particularly significant for the context it provides.

"A body count saying 90,000 Americans or 1.1 million Indians die per year from air pollution is large but faceless," he said. "Saying that, on average, a population lives a year less than they would have otherwise— that is something relatable."

The research received funding through the Center for Air, Climate, and Energy Solutions, an interdisciplinary research collaboration supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Apte was joined in this research by colleagues from University of British Columbia, Imperial College London, Brigham Young University and the Health Effects Institute.