Nov 27 2018

A researcher from Washington State University has for the first time modeled how microplastic fibers travel through the environment.

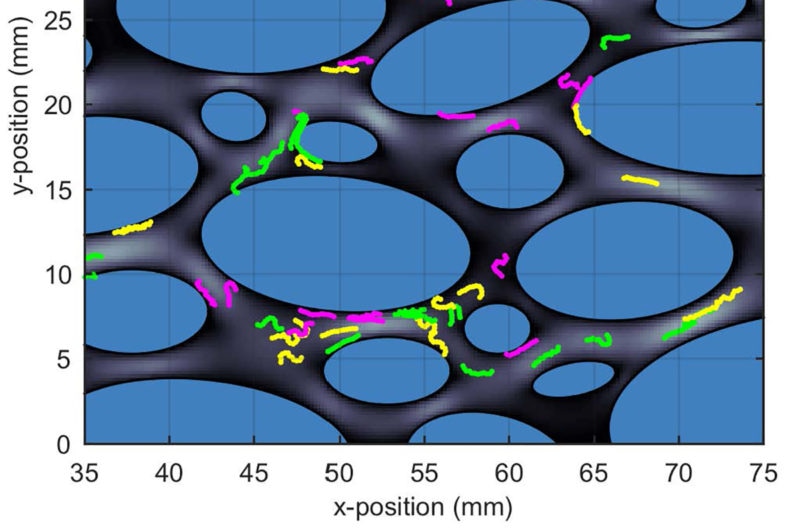

Graphic of the model. The blue ovals represent gravel grains and the bright colored objects represent synthetic fibers. (Credit: Washington State University)

Graphic of the model. The blue ovals represent gravel grains and the bright colored objects represent synthetic fibers. (Credit: Washington State University)

The research, reported in the journal Advances in Water Resources, could one day help societies better understand and minimize plastics pollution, which is a growing issue globally.

Millions of tons of plastic waste in minute microscopic pieces are floating around in the world’s oceans and are ending up in sediments, soil, and freshwater. Plastic debris originates from many sources including synthetic clothing fibers, packaging, cosmetics, and industrial processes. These plastic bits often find its way into the oceans, endangering the marine life that consumes them.

Scientists have analyzed and measured microplastics in numerous environments, but Nick Engdahl, an assistant professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, is the first to model how the synthetic fibers move.

“I wanted to know whether they keep moving and spreading or if they just accumulate in one place,” said Engdahl, who has examined the movement of a range of contaminants in the environment.

He used a novel physics-based method to mimic the movement of microplastic fibers, specifically. These synthetic fibers in clothing are formed during their manufacturing process.

“Every time you walk or rub against something your clothes are shedding fibers,” said Engdahl.

The microfibers, which are mostly released when clothes are washed, end up in wastewater facilities, where a substantial proportion passes through water filtration systems. Even the ones that are filtered enter the sewage sludge that may then be applied to farm soils as fertilizer or deposited in landfills.

Engdahl discovered that the length of the fibers and the speed of water that they are floating in established whether they settle in soil or continue moving in the environment. He also learned that the movement of shorter microplastic fibers was complex, and that they traveled faster than dissolved substances in the water.

Engdahl is aiming to prove and refine his model against direct observations of microplastic fiber movement in a lab. He also plans to measure the fibers in a wastewater treatment plant.

The more data I can get from the real world, the more accurately I will be able to see if these things move around or stay put and pile up. This will help us more accurately measure their environmental impact, which is largely unknown right now.

Nick Engdahl, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Washington State University.