Jan 7 2019

A large number of threats such as pollution, climate change, etc. are putting freshwater supplies at risk. As a result, water collection and purification technologies are becoming more and more significant, particularly in major urban areas.

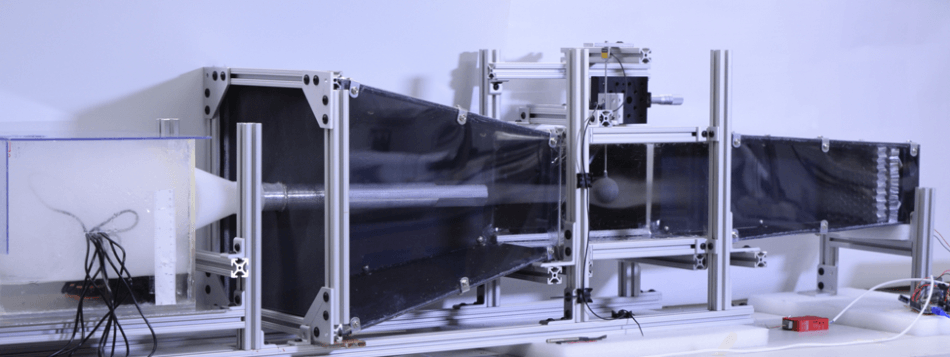

Kings fog tunnel does not look like the typical device one would see in a biology lab. (Image credit: SICB)

Kings fog tunnel does not look like the typical device one would see in a biology lab. (Image credit: SICB)

In places like the San Francisco Bay area, there is limited access to freshwater. In such places, fog collection technologies have inspired a number of engineers looking to arbitrate the dearth of freshwater. For more inspiration, some scientists have started investigating how animals are able to harvest fog for a source of freshwater. Dr Hunter King, who describes himself as more of a physicist than a biologist, is exploring Namib desert beetles to understand how these otherwise water-starved creatures are able to collect water from fog. This extraordinary survival feature lies in the small bumps on the wings of the beetle. King has detailed his finding at the annual meeting for the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology meeting being conducted in Tampa this week.

The exclusive water harvesting traits of this beetle’s wings were initially described around a decade ago. This technology even resulted in a “self-filling” water bottle. Problems persist when one hopes to capitalize on this technology to solve human issues on a larger scale. This is where King enters. The early work carried out by King's colleagues concentrated on the “wettability” of the wing bumps—the ability of the surface to harvest water from fog. Yet, King was inspired to deal with the issue from a different perspective. He addressed whether surface texture could also contribute to the water harvesting efficiency.

Although his inspiration emerged from desert beetles, King has never attempted to experiment with the beetles themselves. He stated, “As far as I’m concerned, it’s all physics. It’s just the biological context has got so much richness and interesting things to look at.”

Rather than beetles, a tunnel allowed King to control the air flow and fog. He places spherical targets that are either rough or smooth in this tunnel. The rough targets were changed in such a way that they look like the bumps found on the wings of the Namib desert beetles. Then, King compared the effectiveness of each target at capturing water with the help of his wind fog chamber. His preliminary findings revealed that rough targets are more efficient at collecting fog since they interrupt the water molecules and then hold them between the bumps. Clearly, regardless of whether the surface is hydrophobic or hydrophilic, fluid dynamics may play a key role in water collecting efficiency. “Just putting a little obstruction will get you a long way in terms of actually catching fog.” Although adding modified “bumps” is comparatively cheap and can easily increase efficiency, altering the surface chemistry of water collecting technologies can be expensive.

King’s findings do not come to an end at his fog tunnel. An unexpected insight is that some species of desert beetles who have bumpy wings may be better suited for harvesting fog, but in fact do not do so. The behavior of these species continues to be a mystery to biologists. These other species may hold further clues to producing tools that can solve human challenges.

The integration of physics and biology enables King to gain insights into both the mechanisms and functions behind organisms’ behaviors. Several lessons can be learned from examining the behaviors of organisms that have succumbed to millions of years of evolution. Evolution has worked out a number of twists behind fog collection behavior in such beetles, and learning from Mother Nature’s tricks may equally benefit engineers as well.