Mar 18 2019

Climate change is now driving away many animals from their comfort zones. This is also evident in the case of disease-carrying mosquitoes that kill almost 1 million people annually.

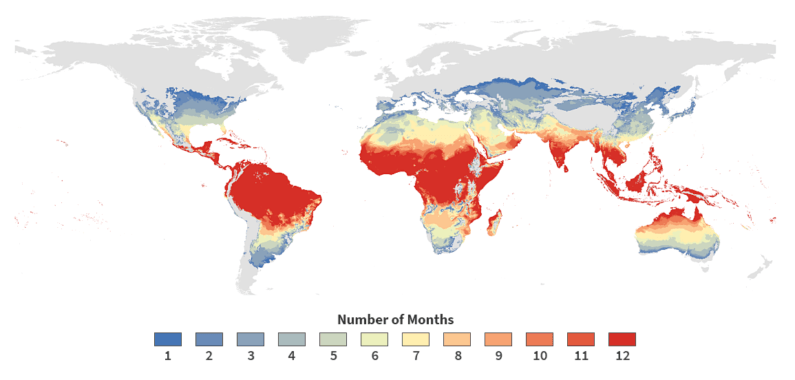

Current worldwide distribution of the mosquito Aedes aegypti—which can spread dengue fever, Zika virus, chikungunya, and yellow fever—by duration of time in each region. (Image credit: Sadie Ryan)

Current worldwide distribution of the mosquito Aedes aegypti—which can spread dengue fever, Zika virus, chikungunya, and yellow fever—by duration of time in each region. (Image credit: Sadie Ryan)

Comfort zones play a key role in the lives of birds and animals because, for instance, when snowbirds flock to warmer climes when winter comes in, wild creatures, on the other hand, seek weather that will suit them.

Erin Mordecai, a biologist at Stanford, together with her colleagues has made shocking predictions of how climate change will bring about changes in where mosquito species will find themselves to be very comfortable and how rapidly they will be able to spread disease, thus targeting the whole world. One key takeaway refers to the fact that countries that are wealthy and developed, like the United States, are not immune.

It’s coming for you. If the climate is becoming more optimal for transmission, it’s going to become harder and harder to do mosquito control.

Mordecai, Biologist, Stanford University

Mosquitoes and several other biting insects are responsible for spreading most of the critical, neglected, and devastating human infectious diseases, including dengue fever, malaria, West Nile virus, and chikungunya. Climate change will surely spread these diseases all over the world, even to the wealthier Northern Hemisphere countries despite the fact that these countries have been, for a long time, kept out of mosquito-borne diseases due to their cooler temperatures and economic development.

As the planet warms, we need to be able to predict what populations will be at risk for infectious diseases because prevention is always superior to reaction.

Desiree LaBeaud, Associate Professor, Pediatrics, Stanford Medical School

LaBeaud was also part of the research with Mordecai.

Through her research, Mordecai discovered that warmer temperatures surge the transmission of vector-borne disease up to a “turn-over point” or an optimum temperature, above which the transmission becomes slow. Different mosquitoes are adapted to a range of temperatures just as they carry different diseases. For instance, malaria is in all likelihood to spread at 25 °C (78 °F), while the risk of Zika is highest at 29 °C (84 °F).

Mordecai’s lab is presently working on forecasting thermal responses for 13 such diseases and the lab also aims at mapping further changes in their distribution accordingly. Until now, the findings reveal that carriers of dengue are found among the warmest adapted, hence they are expected to continue to infect hot regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. However, mosquitoes that have the West Nile virus prefer to have a more temperate climate, hence they are likely to migrate to historically cooler regions such as the United States as the climate becomes warmer.

If you’re thinking about impacts of climate change, this tells you a few degrees of warming has a really different impact depending on where you start relative to the optimum.

Mordecai, Biologist, Stanford University

However, one good news is that higher global temperatures will reduce the chance of most vector-borne diseases spreading in places that are presently relatively warm. The bad news is that warming will result in increasing the chance that all diseases spread in places that are presently relatively cold.

In the meantime, several significant worldwide health initiatives concentrate on cell and molecular biology instead of disease transmission.

I think they’re missing a big area. If you have an ecological change that results in 96 million dengue cases a year, you should target that causal relationship even as you try to find a dengue vaccine and get it to as many people as possible.

Mordecai, Biologist, Stanford University

Mordecai states that it is important to understand and forecast the rise and spread of diseases and also to take into account associated health costs into public policy. “Otherwise, we’re not going to be able to get a handle on this. We’re going to be constantly playing whack-a-mole with whatever the new emerging disease is.”

Mordecai is also a fellow at the Center for Innovation in Global Health. LaBeaud is also a member of the Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. Both Mordecai and LaBeaud are members of Bio-X and affiliates of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.