Apr 2 2019

Scientists at the Rice University have truly found a way to deal with the excess amount of used lithium-ion batteries left behind—a consequence of the growing demand for cellphones, electric vehicles, and other electronic devices.

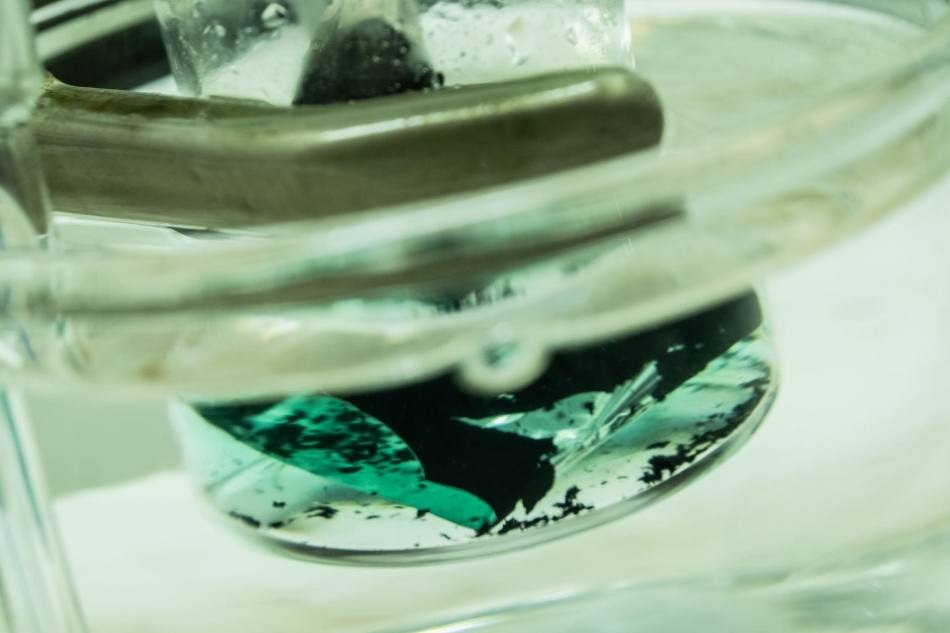

A solution turns green as it pulls cobalt from a spent lithium-ion cathode. A Rice University laboratory is developing an environmentally friendly method to recover valuable metals from used batteries. (Image credit: Jeff Fitlow)

A solution turns green as it pulls cobalt from a spent lithium-ion cathode. A Rice University laboratory is developing an environmentally friendly method to recover valuable metals from used batteries. (Image credit: Jeff Fitlow)

Pulickel Ajayan, materials scientist at the Rice lab, extracted important elements from the metal oxides generally used as cathodes in lithium-ion batteries, using an eco-friendly deep eutectic solvent. The scientists stated that the objective is to limit the use of severe processes to recycle batteries and exclude them from landfills.

The solvent, consisting of choline chloride, ethylene glycol, and commodity products, extracted over 90% of cobalt from powdered compounds, and a smaller yet considerable amount from used batteries.

Rechargeable battery waste, particularly from lithium-ion batteries, will become an increasingly menacing environmental challenge in the future as the demand for these through their usage in electric vehicles and other gadgets increases dramatically. It’s important to recover strategic metals like cobalt that are limited in supply and are critical for the performance of these energy-storage devices. Something to learn from our present situation with plastics is that it is the right time to have a comprehensive strategy for recycling the growing volume of battery waste.

Pulickel Ajayan, Materials Scientist, Rice University

The results have been reported in Nature Energy.

This has been attempted before with acids. They’re effective, but they’re corrosive and not eco-friendly. As a whole, recycling lithium-ion batteries is typically expensive and a risk to workers.

Kimmai Tran, Study Lead Author and Graduate Student, Rice University

She stated that other processes also have limitations. Pyrometallurgy entails crushing and blending at extreme temperatures, and the toxic fumes need scrubbing. Hydrometallurgy needs caustic chemicals, while other “green” solvents that recover metal ions usually need additional agents or high-temperature processes to completely acquire them.

“The nice thing about this deep eutectic solvent is that it can dissolve a wide variety of metal oxides,” stated Tran. “It’s literally made of a chicken feed additive and a common plastic precursor that, when mixed together at room temperature, form a clear, relatively nontoxic solution that has effective solvating properties.”

A deep eutectic solvent is a combination of two or more compounds that freezes at temperatures much lower than each of its precursors. In this manner, one can plainly acquire a liquid from a simple combination of solids, stated Tran.

“The large depression of freezing and melting points is due to the hydrogen bonds formed between the different chemicals,” Tran stated. “By selecting the right precursors, inexpensive ‘green’ solvents with interesting properties can be fabricated.”

When Tran joined, the Rice team was already testing a eutectic solution as an electrolyte in next-generation high-temperature supercapacitors.

We tried to use it in metal oxide supercapacitors, and it was dissolving them. The color of the solution would change.

Babu Ganguli, Co-Corresponding Author and Research Scientist, Rice University

The eutectic was attracting ions from the supercapacitor’s nickel.

“Our team was discussing this and we soon realized we could use what was thought to be a disadvantage for electrolyte as an advantage for dissolving and recycling spent lithium batteries,” Ganguli said.

That turned out to be the focus of Tran, as she tested deep eutectic solvents on metal oxides at various time scales and temperatures. The clear solvent, while testing with lithium cobalt oxide powder, produced a broad spectrum of blue-green colors that showed the presence of cobalt dissolved within.

At 356 ○F (180 ○C), the solvent extracted about 99% of cobalt ions, and almost 90% of lithium ions from the powder when specific conditions were met.

The scientists developed small prototype batteries and cycled them 300 times prior to subjecting the electrodes to the same conditions. The solvent was found to be efficient at dissolving the lithium and cobalt while isolating the metal oxides from the other compounds present in the electrode.

They identified that cobalt could be extracted from the eutectic solution via precipitation or even electroplating to a steel mesh, since this latter technique potentially enabled the deep eutectic solvent itself to be used again.

We focused on cobalt. From a resource standpoint, it’s the most critical part. The battery in your phone will surely have lots of it. Lithium is very valuable too, but cobalt in particular is not only environmentally scarce but also, from a social standpoint, hard to get.

Marco Rodrigues, Postdoctoral Researcher, Argonne National Laboratory

Rodrigues is also an alumnus of Rice University. He remarked that the Department of Energy is taking innovative efforts to improve battery recycling technologies and recently established a center for Li-ion battery recycling.

Further work will need constant efforts.

“It’s likely we won’t be able to recycle and replace mining completely,” stated Tran. “These technologies are relatively new, and there is a lot of optimization that needs to be done, such as exploring other deep eutectic solvents, but we truly believe in the potential for greener ways to do dirty chemistry. Sustainability is in the heart of the work I do and what I want to do for the rest of my career.”

Keiko Kato, a graduate student, is a co-author of the study. Ajayan is the Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor in Engineering and a professor of chemistry.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation through its Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

New ‘blue-green’ solution for recycling world’s batteries

Video credit: Rice University