Apr 10 2019

A new study on how glaciers in the European Alps will cope under a warming climate has turned up some troubling results. Under a limited warming situation, glaciers would lose about two-thirds of their existing ice volume, whereas, under intense warming, the Alps would be typically ice free by 2100. The results, published in the European Geosciences Union (EGU) journal The Cryosphere, were also presented on April 9th at the EGU General Assembly 2019 in Vienna, Austria.

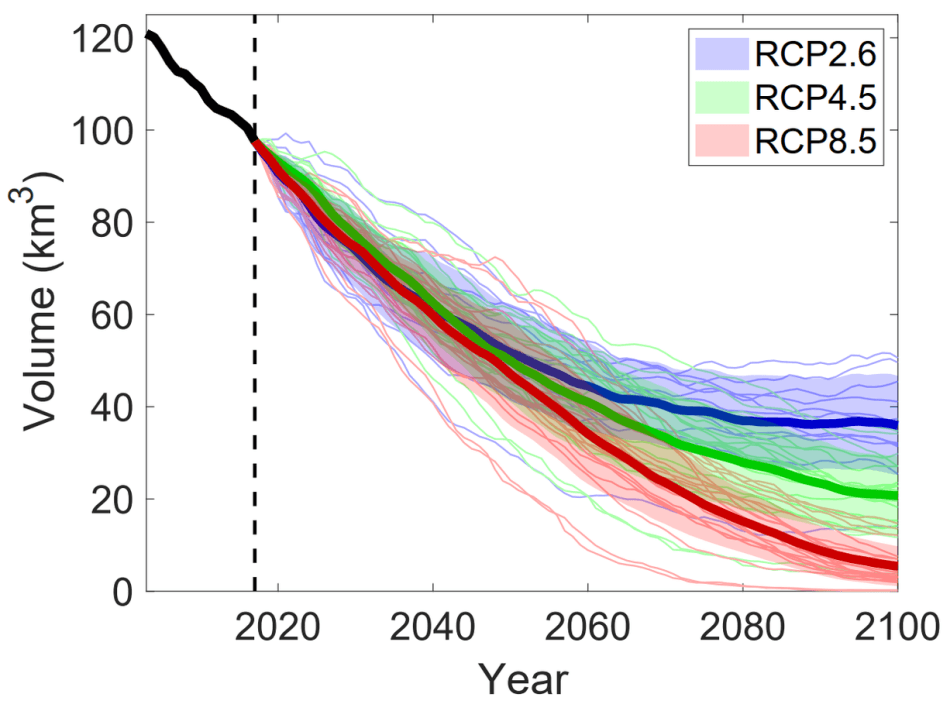

Thin lines represent glacier evolution for a given future climate simulation from the EURO-CORDEX ensemble (51 simulations are considered in total). The thick line is the mean from all simulations for a given RCP (representative concentration pathway), and the shaded area corresponds to the spread around this value. The dotted vertical line represents the year 2017. (Image credit: Zekollari et al., 2019, The Cryosphere)

Thin lines represent glacier evolution for a given future climate simulation from the EURO-CORDEX ensemble (51 simulations are considered in total). The thick line is the mean from all simulations for a given RCP (representative concentration pathway), and the shaded area corresponds to the spread around this value. The dotted vertical line represents the year 2017. (Image credit: Zekollari et al., 2019, The Cryosphere)

The research, by a team of scientists in Switzerland, offers the most current and thorough estimates of the future of all glaciers in the Alps, about 4000. It estimates large deviations to take place in the coming years: from 2017 to 2050, about 50% of glacier volume will vanish, largely independently of how much humans cut the greenhouse gas emissions.

After 2050, “the future evolution of glaciers will strongly depend on how the climate will evolve,” says study-leader Harry Zekollari, a scientist at ETH Zurich and the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, currently at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. “In case of a more limited warming, a far more substantial part of the glaciers could be saved,” he says.

Glacier retreat would have a huge impact on the Alps as glaciers are a crucial part of the region’s landscape, ecosystem, and economy. They draw tourists to the mountain ranges and serve as natural freshwater reservoirs. Glaciers offer a source of water for flora and fauna, as well as for hydroelectricity and agriculture, which is particularly vital in warm and dry seasons.

To learn out how Alpine glaciers would fare in a warming world, Zekollari and his co-authors used new computer models (integrating ice flow and melt processes) and observational data to examine how each of these ice bodies would alter in the future for various emission scenarios. They used 2017 as their “present day” reference, a year when Alpine glaciers possessed a total volume of about 100 km3.

Under a condition suggesting limited warming, called RCP2.6, emissions of greenhouse gases would increase in the following few years and then drop rapidly, maintaining the level of added warming at the end of the century below 2 °C since pre-industrial levels. In this scenario, Alpine glaciers would be decreased to about 37 km3 by 2100, merely over one-third of their current volume.

Under the high-emissions situation, equivalent to RCP8.5, emissions would continue to grow quickly over the following few decades. “In this pessimistic case, the Alps will be mostly ice free by 2100, with only isolated ice patches remaining at high elevation, representing 5% or less of the present-day ice volume,” says Matthias Huss, a researcher at ETH Zurich and co-author of The Cryosphere study. Global emissions are presently just above what is estimated by this scenario.

The Alps would lose around 50% of their existing glacier volume by 2050 in all circumstances. A reason why volume loss is typically independent of emissions until 2050 is that increases in mean global temperature with rising greenhouse gases only become more marked in the second half of the century. Another reason is that glaciers currently have “too much” ice: their volume, particularly at lower elevations, still echoes the colder climate of the past because glaciers are slow at reacting to changing climate conditions. Even if man can manage to halt the climate from warming any more, keeping it at the level of the last 10 years, glaciers would still lose approximately 40% of their present-day volume by 2050 because of this “glacier response time,” says Zekollari.

Glaciers in the European Alps and their recent evolution are some of the clearest indicators of the ongoing changes in climate. The future of these glaciers in indeed at risk, but there is still a possibility to limit their future losses.

Daniel Farinotti, Senior Co-Author, ETH Zurich