May 23 2019

Methane is a powerful potent greenhouse gas that is known to capture roughly 30 times more heat when compared to carbon dioxide. This greenhouse gas is often emitted by landfills, dairies, rice fields, and oil and gas plants—all of which are found abundantly in California.

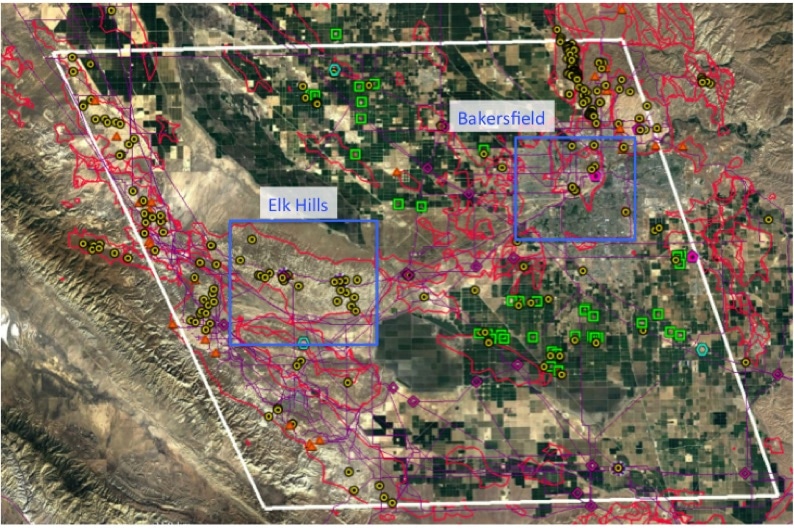

Berkeley Lab’s new project to identify and mitigate methane “super-emitters” will focus on the area in the white polygon. The smaller colored polygons show the diversity of methane emission sources and infrastructure in the area, with oil and gas fields in red, dairies in green, landfills in cyan, and natural gas infrastructure in purple. (Image credit: Berkeley Lab)

Berkeley Lab’s new project to identify and mitigate methane “super-emitters” will focus on the area in the white polygon. The smaller colored polygons show the diversity of methane emission sources and infrastructure in the area, with oil and gas fields in red, dairies in green, landfills in cyan, and natural gas infrastructure in purple. (Image credit: Berkeley Lab)

The state has recently awarded $6 million to the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) to locate “super-emitters” of methane in an attempt to measure and possibly alleviate the emissions of methane gas.

The California Energy Commission grant will allow the project to concentrate on the southern San Joaquin Valley, an area where the oil and gas sector and the dairy sector are the main sources of the methane gas.

In this regard, Berkeley Lab is working in association with UC Riverside, Stanford University, Scientific Aviation, the Central California Asthma Collaborative, and Bluefield on the new project, called SUper eMitters of Methane detection using Aircraft, Towers, and Intensive Observational Network, or SUMMATION for short.

The existing methane accounting and monitoring frameworks in California are limited in their ability to resolve emissions at the scale of individual cities or facilities, such as an oil and gas field or a natural gas processing facility, much less individual components. The idea for this project is based on the development of a tiered observation system.

Sébastien Biraud, Study Lead, Scientist, and Head, Climate Sciences Department (CESD), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

The scientists, on their part, will be tracking and measuring the emissions of methane gas at various scales, from facility to regional and component scales. Detection strategies include running field operations to test novel technologies such as low-cost sensors; gathering air samples from a network of aircraft and fixed towers; surveying commercial and residential buildings; and driving across the region using on-road vehicles fitted with a wide range of equipment.

We will show the state how methane emission quantification can be done over a complex region, and hopefully demonstrate that our approach can be replicated in a cost-effective manner to other areas of interest in California, such as the San Francisco Bay Area or the Sacramento region. The goal is to design a framework, show that it works, and expand it throughout the state.

Sébastien Biraud, Study Lead, Scientist, and Head, Climate Sciences Department (CESD), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Challenges of accurate methane monitoring

Methane gas is categorized as a short-lived climate pollutant because it remains in the atmosphere for only a decade; by contrast, carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for approximately 100 years and is also the most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas known to date. Under a number of laws and executive orders, California has been directed to lower its greenhouse gas emissions and therefore the state has given priority to reduce short-lived climate pollutants as a means to make a more instant beneficial effect on public health and climate change.

For instance, this state approved the California Cooling Act last year forbidding specific hydrofluorocarbons in newly manufactured refrigeration and air conditioning systems. After the Aliso Canyon disaster in 2015, in which an enormous amount of natural gas leaked from a storage facility located in Southern California, California implemented an air regulation that required quarterly observation of the emission of methane gas from natural gas processing facilities, oil and gas wells, and other equipment utilized in the processing and transportation of oil and natural gas.

In addition, the air regulation takes regular inventories of greenhouse gas emissions in California, but despite this fact, a number of studies, including the one carried out by Berkeley Lab, have discovered that official inventories might well be underestimating the emission of methane gas.

In particular, the southern San Joaquin Valley does not have consistent atmospheric observations of methane. Together with the difficulties associated with this region’s sources, this gives way to considerable uncertainties in the total distribution (over time, space, and sector) and magnitude of the emission of methane gas in this region.

Most methane emissions from super emitters

Big emitters are the main target of the SUMMATION project.

Methane emissions could be in the form of a distributed area of small leaks, which is difficult to address, or from a large super emitter, which is low-hanging fruit. A statewide methane survey led by NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory from 2015 through 2017 found that 80% of methane emissions in California are from 25% of sources; in some cases, as few as 1% of sources contribute more than half the emissions. A super emitter could be a dairy, it could be a landfill that’s not well maintained, or it could be a leaking natural gas compressor station.

Sébastien Biraud, Study Lead, Scientist, and Head, Climate Sciences Department (CESD), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Detection and monitoring can be improved through numerous collection techniques, including frequent and continuous field operations.

“Many sources are not persistent—they could be on for a few months, then off,” Biraud stated. “If you just do surveys one or two times a year, you’re fishing. You might see a source, you might not. With a persistent network of towers, you address the nature of intermittent sources.”

Tracers will be used by the SUMMATION project team to help attribute the source of methane gas. For instance, some alkanes (like ethane) are present in the methane gas released by oil and gas operations but they are not present in the same methane gas emitted by dairy operations.

One major part of the SUMMATION project is to assess cost-effective methane sensors.

There are new technologies emerging. We’ll invite companies to participate, then deploy some of them over a one-year period.

Sébastien Biraud, Study Lead, Scientist, and Head, Climate Sciences Department (CESD), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

These observations combined with data analysis from the tiered observation system framework created in Kern County will allow the Berkeley Lab researchers to carry out a low-cost analysis to look for affordable methods to deploy some of these new technologies and thus deal with specific questions in other regions of the state.

Stakeholder and community engagement is another major aspect of the SUMMATION project. “We’ll be reaching out to disadvantaged communities, both to educate them on methane emissions and also to hear about their concerns in order to inform the development of future measurement systems,” Biraud stated. “These communities are affected disproportionately by methane and VOCs [volatile organic compounds].”