May 30 2019

In popular culture, the rose may be one of the most iconic representations of the delicateness of love; however, now, the flower could possess more than just symbolic value.

(Image credit: Cockrell School of Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin)

(Image credit: Cockrell School of Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin)

Inspired by a rose, The University of Texas at Austin developed a new device for collecting and purifying water. While more engineered than enchanted, it is a remarkable enhancement on existing techniques. Each flower-like structure can produce over half a gallon of water per hour per square meter and costs less than 2 cents.

A group headed by associate professor Donglei (Emma) Fan in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering created a new methodology to solar steaming for water production—a method that employs energy from sunlight to isolate salt and other impurities from the water via evaporation.

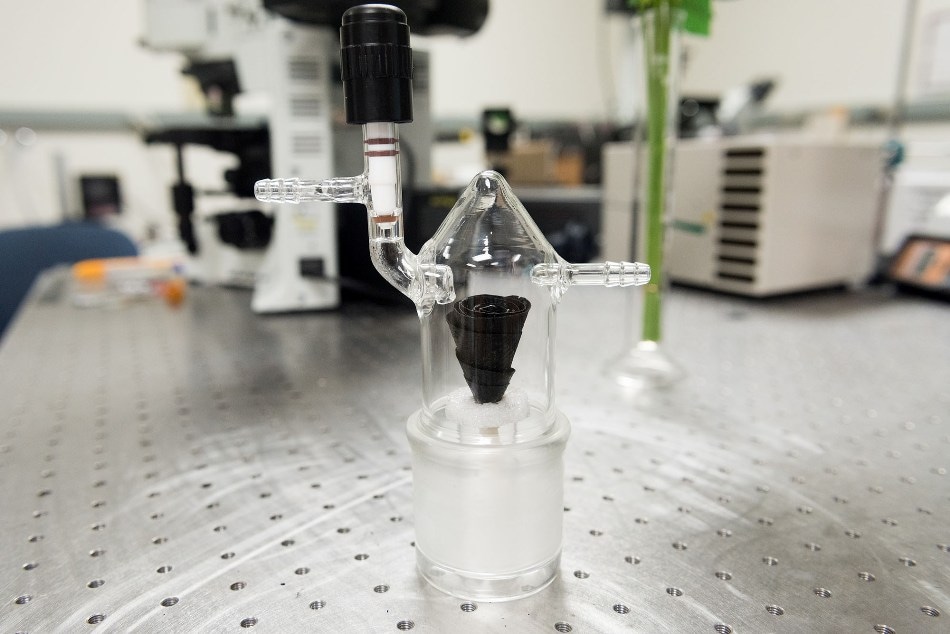

In a paper reported in the latest issue of the journal Advanced Materials, the authors delineate how an origami rose offered the idea for creating a new type of solar-steaming system composed of layered, black paper sheets shaped into petals. The 3D rose shape is connected to a stem-like tube that gathers untreated water from any water source. This structure makes it easier to collect and hold more liquid.

Existing solar-steaming technologies are typically costly, large, and offer limited outcomes. The group’s technique uses reasonably priced materials that are portable and lightweight. Moreover, it appears just like a black-petaled rose in a glass jar.

Cognizant persons would more precisely define it as a portable low-pressure controlled solar-steaming-collection “unisystem.” However, its resemblance to a flower is no coincidence.

We were searching for more efficient ways to apply the solar-steaming technique for water production by using black filtered paper coated with a special type of polymer, known as polypyrrole.

Professor Donglei Fan, Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering, Cockrell School of Engineering

Polypyrrole is a material recognized for its photothermal properties, implying it is predominantly good at turning solar light into thermal heat.

Fan and her group experimented with many different means to shape the paper to find what was best for attaining optimal water retention levels. They started by laying single, round layers of the coated paper flat on the ground under direct sunlight. The single sheets held potential for water collectors but not in adequate quantities.

After considering a few other shapes, Fan was motivated by a book she read in high school. While not about roses as such, “The Black Tulip” by Alexandre Dumas offered her the idea to try using a flower-like shape, and she found the rose to be perfect. Its structure enabled more direct sunlight to strike the photothermic material—with more internal reflections—when compared to other floral shapes and also offered an enlarged surface area for water vapor to dissipate from the material.

The device gathers water from its stem-like tube—offering it to the flower-shaped structure on top. Also, it can gather rain drops falling from above. Water finds its way to the petals where the polypyrrole material covering the flower converts the water into steam. Impurities naturally isolate from water when condensed in this manner.

We designed the purification-collection unisystem to include a connection point for a low-pressure pump to help condense the water more effectively. Once it is condensed, the glass jar is designed to be compact, sturdy and secure for storing clean water.

Weigu Li, Study Lead Author and PhD candidate, Fan’s lab, The University of Texas at Austin

The device eliminates any contamination from heavy metals and bacteria, and it eliminates salt from seawater, yielding clean water that satisfies drinking standard requirements set by the World Health Organization.

“Our rational design and low-cost fabrication of 3D origami photothermal materials represents a first-of-its-kind portable low-pressure solar-steaming-collection system,” stated Li. “This could inspire new paradigms of solar-steaming technologies in clean water production for individuals and homes.”

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Welch Foundation.