Aug 14 2019

Scientists at the University of South Florida are utilizing the power of human physiology to turn greenhouse gases into operational chemical compounds—a method that could help decrease industrial reliance on petroleum and lower carbon footprint.

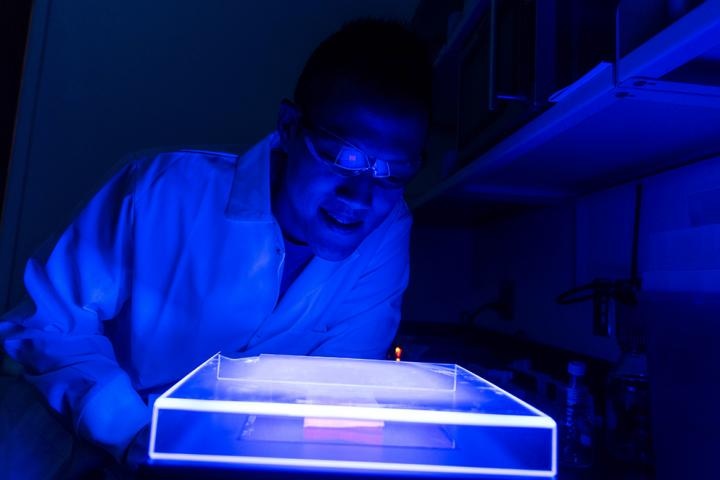

USF researcher Alex Chou manipulates DNA to engineer E. coli for C1 conversion. (Image credit: University of South Florida)

USF researcher Alex Chou manipulates DNA to engineer E. coli for C1 conversion. (Image credit: University of South Florida)

The new biologically-based method, reported in Nature Chemical Biology, was formulated by USF Professor Ramon Gonzalez, PhD, and his research team. It utilizes the human enzyme, 2-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A lyase (HACL), to change particular one-carbon (C1) materials into more complex compounds frequently used as the building blocks for numerous industrial and consumer products.

“In humans, this enzyme degrades branched chain fatty acids,” Gonzalez said. “It basically breaks down long carbon chains into smaller pieces. We needed it to do the opposite. So, we engineered the process to work in reverse—taking single carbon molecules and converting them into larger compounds.”

By controlling the DNA encoding the enzyme, scientists could insert the altered enzyme into E. coli microorganisms, which serve as hosts. When those microbes are added to C1 feedstock, such as formate, methanol, carbon dioxide, formaldehyde, and methane, a metabolic bioconversion process occurs, changing the molecules into more complex compounds.

This study signifies an important breakthrough in biologically-based carbon conversion and has the potential to alter current petrochemical processes as well as decrease the amount of greenhouse gas discharged into the air during the production of crude oil.

When crude oil is pumped out of the ground, it comes with a lot of associated gas. Much of the time, that gas is burned off through flaring and released into the atmosphere. We see that gas as a wasted resource.

Ramon Gonzalez, PhD, Professor, USF

Through their work, Gonzalez feels he and his team have designed a technique to utilize wasted resources in a way that is economically reasonable and appealing for oil manufacturers.

At present, the huge majority of oil production plants utilize flaring to burn-off gas such as methane. While that method is wasteful, according to Gonzalez, it is also unproductive and results in the emission of extra, unburned methane into the air as well as extra carbon dioxide generated through the burning process.

By executing the USF-developed method, oil producers could not only properly manage their impact on the environment but also start making valuable chemical compounds such as ethylene glycol and glycolic acid—molecules that are used in the manufacture of plastics, polymers, cosmetics, cleaning solutions, etc.

Traditionally, the building blocks for these products are created using petroleum. So, while applying the bioconversion technique would help decrease greenhouse gas emissions, it also has the potential to lower the overall reliance on petroleum—numerous benefits that Gonzalez hopes will interest manufacturers to look into adopting their process.

While this study details the overarching science that makes all of this possible, we are currently working with partners in the private sector to try and implement our technique. It’s exciting to be able to take this project from its initial inception all the way to industrial implementation and hopefully have a meaningful impact on not just the industry but to the environment as well.

Ramon Gonzalez, PhD, Professor, USF