Sep 23 2019

Scientists from Kyushu University studied seismic pressure wave reflections from the subseafloor geology off southwestern Japan and have discovered the first proof for the existence of an enormous gas reservoir at the point where the Earth’s crust is separated.

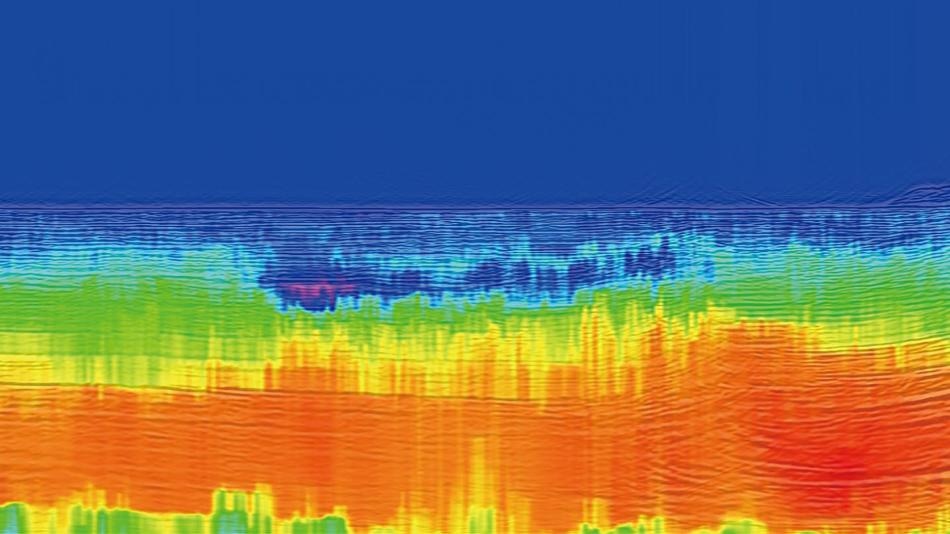

(Image credit: Takeshi Tsuji, Kyushu University)

(Image credit: Takeshi Tsuji, Kyushu University)

Based on its nature, the trapped gas could turn out to be a promising unexploited natural resource or a source of greenhouse gases waiting to escape, increasing the need to better perceive similar reservoirs across the globe.

Although the surface of the ocean appears calm, ocean depths can undergo violent thermal activity as hot magma oozes from locations at which the upper layers of Earth are being pulled apart—a process known as rifting.

Elevated levels of methane gas and carbon dioxide can occur in the water in such areas, probably escaping from magma or being generated by microbial organisms or the interaction of hot water with organic-rich sediment.

In a new study reported in Geophysical Research Letters, scientists from Kyushu University’s International Institute for Carbon-Neutral Energy Research (I2CNER) have described that some of these gases may, in fact, get locked up underground, resulting in the occurrence of an enormous gas reservoir underneath the axis along which rifting has been taking place in the Okinawa Trough.

The scientists endeavored to find the reservoir by analyzing measurements of the way seismic pressure waves produced by an acoustic source, which is carried by boat to the area of study, are reflected by geological structures.

The researchers applied an automated calculation method to this seismic data, thus developing a 2D map of the velocities at which the pressure waves move through the ground with a considerably higher resolution compared to earlier manual methods.

Seismic pressure waves generally travel more slowly through gases than through solids. Thus, by estimating the velocity of seismic pressure waves through the ground, we can identify underground gas reservoirs and even get information on how saturated they are. In this case, we found low-velocity pockets along the rifting axis near Iheya North Knoll in the middle of the Okinawa Trough, indicating areas filled with gas.

Andri Hendriyana, Study Co-Author, Kyushu University

At this point, the scientists are not yet convinced whether the reservoirs are predominantly filled with methane or carbon dioxide. If it is methane, the gas could be a promising natural resource. But both methane and carbon dioxide contribute to the greenhouse effect. Therefore, the fast, uncontrolled discharge of either gas from such a huge reservoir could have considerable environmental implications.

While many people focus on greenhouse gases made by humans, a huge variety of natural sources also exist. Large-scale gas reservoirs along a rifting axis may represent another source of greenhouse gases that we need to keep our eyes on. Or, they could turn out to be a significant natural resource.

Takeshi Tsuji, Study Corresponding Author, Kyushu University

One explanation for how the gas is locked up could be layers of impermeable sediment like clay could inhibit the escapes of the gas from porous underlying layers of materials like pumice. After analyzing the heat flow around the area of study, the scientists consider that another explanation could be that a low-permeability cap of methane hydrate—a methane-containing ice—functions as the lid.

Zones like the one we investigate are not uncommon along rifts, so I expect that similar reservoirs may exist elsewhere in the Okinawa Trough as well as other sediment-covered continental back-arc basins around the world.

Takeshi Tsuji, Study Corresponding Author, Kyushu University