Apr 29 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decline in the demand for transportation fuels in the last month.

Image Credit: Northern Arizona University.

Image Credit: Northern Arizona University.

According to a researcher from the Northern Arizona University (NAU), the drastic decline in local carbon dioxide (CO2) and air pollution levels over the urban areas is considerable, quantifiable, and could be historic, based on how long commuters and other drivers stay away from the road.

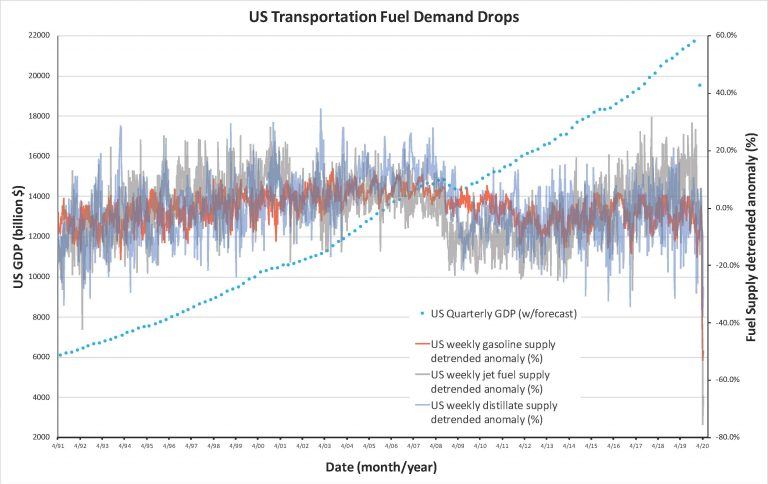

Kevin Gurney, a professor from NAU’s School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems, quantifies greenhouse gas emissions in major cities of the United States. He notes that the use of three vital fuels has decreased considerably: jet fuel, distillate (diesel), and gasoline.

For the first three weeks of April, gasoline has declined 43.1 percent, jet fuel by 59.3 percent and diesel fuels by 16.7 percent compared to the same three weeks over the last decade. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think it was an error in the data. Nothing like this has ever shown up in the record. Never.

Kevin Gurney, Professor, School of Informatics, Computing and Cyber Systems, Northern Arizona University

Each year, vehicles that drive on the road account for approximately 20% of CO2 emissions.

The decline in gasoline has implications for both local air quality and climate change. We never could have run an experiment in which the public stops driving. The COVID-19 virus has forced this, and it gives us a glimpse of what not driving does to our air.

Kevin Gurney, Professor, School of Informatics, Computing and Cyber Systems, Northern Arizona University

Data previously obtained from both ground and satellite monitors indicate reduced local air pollution in several places across the United States, in correlation with the decrease in fuel consumption. Using data collected from mid-March this year, Gurney has predicted longer-term levels of climate change gases in the air if the demands for transportation fuel continue to be low.

Gurney stated, “If one were to assume that gasoline, jet fuel and distillates persisted at the current levels until the end of June, this would result in an annual decline of 5 percent in CO2 emissions from total energy for 2020. If the current levels persisted for 12 months, or until the end of February 2021, this would result in an annual decline of CO2 emissions of roughly 15 percent.”

As a reference point, Gurney compared the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the use of petroleum fuel with those of the worldwide financial crisis of 2008 on its use, when CO2 emissions declined by 3%.

“This far exceeds that event in terms of fuel consumption data we can see, but we’ve only had a few weeks to measure the results. We don’t know how this is going to show up over the long haul. Once the pandemic is over, we may go right back to our normal levels of greenhouse gas emissions,” noted Gurney.

However, there may be positive outcomes for climate in the midst of this devastating social and economic event. For example, business owners may see opportunities to continue telecommuting with a portion of the workforce and thereby increase productivity and lower costs. This could lessen road traffic and increase the efficiency of commercial space.

Kevin Gurney, Professor, School of Informatics, Computing and Cyber Systems, Northern Arizona University

Gurney continues to record several CO2 emission datasets as part of his Hestia and Vulcan projects, which involve mapping emissions at fine scales throughout the U.S. landscape.

“From a climate change point-of-view, there may be some valuable insights on energy consumption that we can use as we emerge from the COVID-19 crisis,” Gurney concluded.