Jun 16 2020

A majority of the individuals have seen informational posters at aquariums or parks, specifying the lifetime of plastic bottles, bags, and other products in the environment.

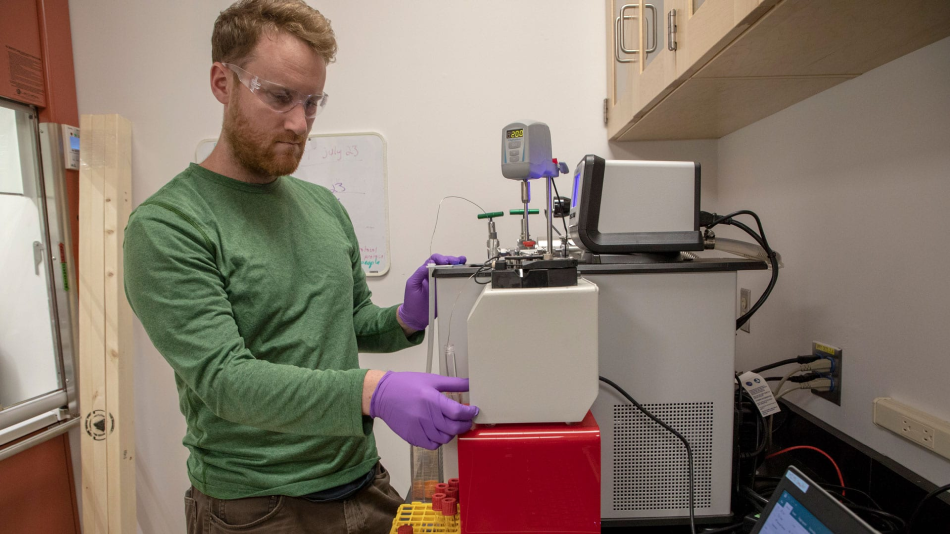

Marine chemist Collin Ward working in his lab. Image Credit: Photo by Jayne Doucette, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Marine chemist Collin Ward working in his lab. Image Credit: Photo by Jayne Doucette, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

While these products are a good reminder to refrain from littering the environment, researchers are unaware of the actual source of information regarding the lifetime expectancy of plastic goods, and the extent of its reliability.

However, getting a true picture of the time taken by plastics to disintegrate in the environment is a complicated business, stated Collin Ward, a marine chemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and also a member of the Microplastics Catalyst Program—an established research program focused on plastics in the ocean.

Plastics are everywhere, but one of the most pressing questions is how long plastics last in the environment. The environmental and human health risks associated with something that lasts one year in the environment, versus the same thing that lasts 500 years, are completely different.

Collin Ward, Study Lead Author and Marine Chemist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

It may be tricky to know the fate of plastics, but nevertheless crucial. Researchers require the information to figure out the fate of plastics in the environment and evaluate the related health risks; consumers require it to make sound and sustainable decisions; and legislators require it to make informed decisions around plastic prohibitions.

Considering the age-old mystery surrounding the life expectancy of plastic goods, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution conducted a new study to analyze how the lifetime estimates of bags, cups, straws, and other products are being conveyed to the general public through infographics.

Ward, the lead author of the latest article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, together with Chris Reddy, a marine chemist from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, examined almost 60 individual documents and infographics from a wide range of sources, such as social media sites, non-profits, textbooks, and governmental agencies.

The team was surprised to note that there were major inconsistencies in the lifetime estimates numbers cited for various day-to-day products, including plastic bags, among the materials.

“The estimates being reported to the general public and legislators vary widely,” added Ward. “In some cases, they vary from one year to hundreds of years to forever.”

On the other hand, specific lifetime estimates appeared much too analogous among the infographics. Of specific interest were the estimates for how long the fishing line endures in the ocean, noted Ward. According to him, all 37 infographics that comprised a lifetime for fishing line reported 600 years.

Every single one said 600 years, it was incredible. I’m being a little tongue-in-cheek here, but we’re all more likely to win the lottery than 37 independent science studies arriving at the same answer of 600 years for fishing line to degrade in the environment.

Collin Ward, Study Lead Author and Marine Chemist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

As a matter of fact, these estimates did not emerge from real scientific analyses. Ward added that he did a great deal of research to trace peer-reviewed literature that was either conducted, or funded, by the agencies responsible for putting the data out there and could not identify a single case where the estimates emerged from a scientific research.

According to Ward and Reddy, while the data was probably well-intentioned, the absence of documented and traceable science behind it was a red flag.

“The reality is that what the public and legislators know about the environmental persistence of plastic goods is often not based on solid science, despite the need for reliable information to form the foundation for a great many decisions, large and small,” stated the researchers in the study.

In their own peer-reviewed study focusing on the life expectancy of plastics published the previous year, Ward and his research team found that polystyrene—one of the most ubiquitous plastics in the world—may degrade in many years upon exposure to sunlight, rather than thousands of years as believed before.

The finding was partly made by working with scientists at the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (NOSAMS) facility in Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to follow the degradation of the plastic into water and gas phases, and with the help of a dedicated weathering chamber installed in Ward’s laboratory.

The weathering chamber tested how environmental factors such as temperature and sunlight impacted the chemical breakdown of the polystyrene—the original form of plastic detected in the coastal ocean by researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution almost five decades ago.

According to Reddy, one of the major misunderstandings relating to the fate of plastics in the environment is that they merely disintegrate into smaller pieces that exist permanently.

This is the narrative we see all the time in the press and social media, and it’s not a complete picture. But through our own research and collaborating with others, we’ve determined that in addition to plastics breaking down into smaller fragments, they also degrade partially into different chemicals, and they break down completely into CO2.

Chris Reddy, Marine Chemist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

These recently detected breakdown products no longer look like plastic and would otherwise be overlooked when researchers explore the oceans for missing plastics.

According to Chelsea Rochman, a biologist at the University of Toronto and who was not a part of the research, interpreting the different forms of the degradation of plastics will be integral to solve one of the long-standing mysteries of plastic pollution: over 99% of the plastic that should be identified in the ocean is missing.

“Researchers are beginning to talk about the global plastic cycle,” added Rochman. “A key part of this will be understanding the persistence of plastics in nature. We know they break down into smaller and smaller pieces, but truly understanding mechanisms and transformation products are key parts of the puzzle.”

On the whole, the researchers gained a true picture by examining the infographics and this underscored the significance of backing public data with sound science.

“The question of environmental persistence of plastics is not going to be easy to answer. But by bringing transparency to this environmental issue, we will help improve the quality of information available to all stakeholders—consumers, scientists, and legislators—to make informed, sustainable decisions,” concluded Ward.

The study was financially supported by The Seaver Institute and internal funding from the WHOI Microplastics Catalyst Program.

Journal Reference:

Ward, CP & Reddy, CM (2020) Opinion: We need better data about the environmental persistence of plastic goods. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008009117.