Jun 9 2021

According to a new global study, greenhouse-gas emissions from food systems have been systematically underestimated for a long time — but there are significant opportunities to reduce them.

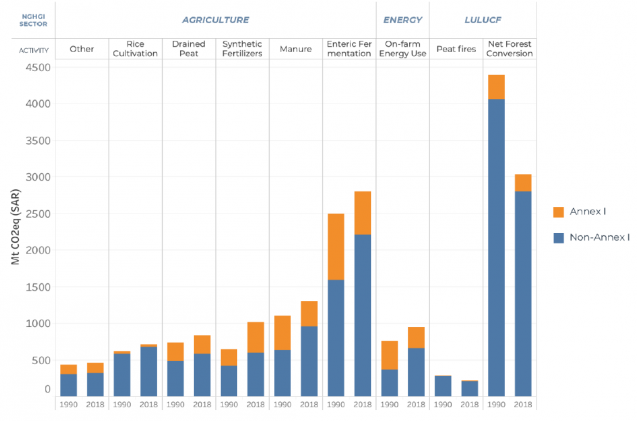

Greenhouse-gas contributions from various parts of the global food system. Image Credit: Tubiello et al., Environmental Research Letters 2021.

Greenhouse-gas contributions from various parts of the global food system. Image Credit: Tubiello et al., Environmental Research Letters 2021.

The researchers estimate that activities associated with the production and consumption of food created the equivalent of 16 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2018 — that is one-third of the human-produced total and an increase of 8% since 1990.

A companion policy paper has also emphasized the need to combine research with measures to cut down emissions. The articles, co-developed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, NASA, New York University, and experts from Columbia University, are part of a special issue of the journal Environmental Research Letters on sustainable food systems.

The Center on Global Energy Policy has created a comprehensive guide to climate and food systems and a related video, both aimed toward the general public.

Francesco Tubiello, the lead author of the study heads the environment statistics unit at FAO. According to him, the new analysis shows that food production represents a “larger greenhouse-gas mitigation opportunity than previously estimated, and one that cannot be ignored in efforts to achieve the Paris Agreement goals.”

Emissions inventories that nations presently report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change do not clearly define food systems and tend to underestimate their role in climate change.

The study offers country-level datasets that are being refined ahead of the UN’s Food Systems Summit, to be conducted in July 2021. This analysis considers emissions that are linked not only to crop and livestock production but also to land-use variations at the boundary between natural ecosystems and farms as well as to relevant manufacturing, storage, processing, waste disposal, and transport.

The companion policy piece urges for improved scientific insight into the processes by which greenhouse gases are discharged from all phases of food production and consumption. It stated that the food system has a significant role to play in reducing climate change.

Science and policy domains have often been siloed in academia. We propose a ‘double helix’ of interactive research by scientists and policy experts that can deliver significant benefits for both climate change and the food system.

Cynthia Rosenzweig, Study Lead Author, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Earth Institute Columbia University

“The food system and the climate system are deeply intertwined. Better data can help lead to better policies for cutting emissions and protecting the food system from a changing climate,” stated David Sandalow, the study co-author and a fellow at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

According to the authors, policies and programs to reduce climate change should consider the effect on more than 500 million smallholder households worldwide. This issue is particularly apparent in the least-developed nations, where comparatively larger shares of the population depend on agriculture for their livelihoods.

To achieve a net-zero future, we need to understand better the interplay between the food system and emissions in developing countries where populations are growing, poverty is diminishing, and incomes are rising.

Philippe Benoit, Adjunct Senior Research Scholar, Center on Global Energy Policy, Earth Institute at Columbia University

Improved mitigation techniques are one emergent theme that will need to focus on activities both before and after farm production, spanning from the industrial production of fertilizers to refrigeration at the retail level. Emissions from such activities are growing quickly.

Agriculture in developed countries emits large quantities of greenhouse gases, but their share can be obscured by large emissions from other sectors like electricity, transportation, and buildings. Looking at the entire food system can not only illuminate opportunities to reduce emissions from agriculture, but also improve efficiency across the whole supply chain with technologies such as refrigeration and storage.

Matthew Hayek, Study Co-Author and Assistant Professor in Environmental Studies, New York University

The researchers noted that while total food-systems emissions increased from 1990 to 2018, changing technologies and rising populations meant that per capita emissions were actually reduced from the equivalent 2.9 metric tons to 2.2 metric tons for every person. However, per capita emissions in developed nations, at 3.6 metric tons per person in 2018, were almost twice those in developing nations.

The transformation of natural ecosystems to agricultural pastures or croplands continued to be the single largest emissions source over the study period, at almost three billion metric tons annually. However, it dropped considerably over time, by more than 30%, partly because people are running out of land to transform.

On the contrary, global emissions from domestic food transportation have increased by almost 80% since 1990, to 500 million tons in 2018. Such emissions have almost tripled in developing nations. Similarly, emissions produced by food system energy use, mostly carbon dioxide from fossil fuels along the supply chain, contributed to more than four billion tons in 2018, which is an increase of 50% since 1990.

Food and Climate Change

In this video, the authors describe the tight links between food systems and climate, and what we can do to reduce emissions. Video Credit: Earth Institute at Columbia University.