Photosynthesis is the complex biochemical process by which green plants and a number of other organisms transform the Sun’s energy into chemical energy. During this process, the captured light energy is used to convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into oxygen and energy-rich compounds such as sugar molecules.

Study: Interdependent iron and phosphorus availability controls photosynthesis through retrograde signaling. Image Credit: Zamurovic Brothers/Shutterstock.com

A team of researchers from Carnegie, Michigan State University (MSU), and the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment in France has published a study that details findings around a complex low-chlorophyll iron deficiency that hinders photosynthesis known as chlorosis.

The research published in the journal Nature Communications could pave the way towards developing even more eco-friendly agricultural practices and new food crop resilience strategies using less water and fertilizer.

The Importance of Chlorophyll

Photosynthesis in green plants is largely driven by the pigment chlorophyll, which is essential in a plant’s ability to absorb light and has implications that extend beyond light absorption properties. It also impacts the capacity for the plant to produce food, and plants suffering from chlorosis often turn yellow.

Chlorosis is typically caused by a nutrient deficiency such as iron, or soil pH sometimes plays a role in nutrient-caused chlorosis; a number of plants have adapted to grow in soils with specific pH levels, and their capacity to absorb nutrients from the soil may rely on these pH values.

Understanding Chlorosis

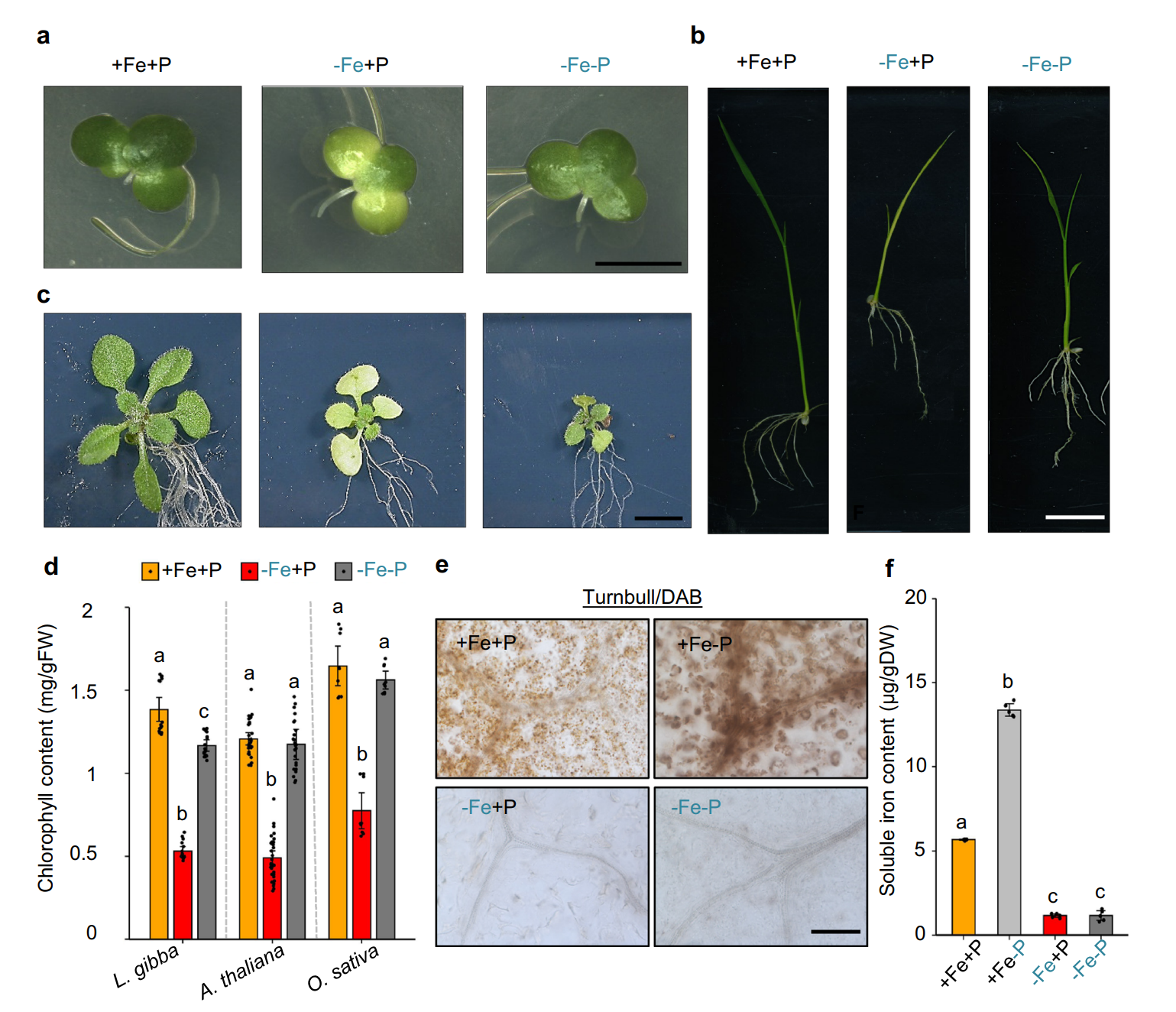

Nutrients build up in the chloroplasts and play a critical role in the function of the green pigments. The researchers demonstrated that iron and phosphorous were the key nutrients in the prevention of chlorosis. This goes against the grain of previous assumptions that reduced iron levels alone were the sole cause of chlorosis in plants.

To better understand the factors that lead to chlorosis and to plant leaves looking yellow, the team evaluated the collective response of various nutrients rather than breaking them down one by one.

Phosphorus deficiency prevents iron deficiency-induced chlorosis in evolutionarily distant plant species. Image Credit: Nam, H. and Shahzad, Z., et al.

The team discovered that even if a plant was demonstrating iron deficiency, with the removal and regulation of phosphorous, the plant leaves regained their green color by accumulating chlorophyll again.

These results provide fundamental new insights into chlorophyll accumulation and photosynthesis under Fe limitation and identify a signaling pathway that may coordinate plastid–nuclear communication as a means to adapt photosynthesis to nutrient availability.

Hatem Rouached, Lead Author and Assistant Professor at MSU

Fertilizer Management Strategies

In short, the reasoning for this unexpected response results from the signaling where photosynthesis occurs and where the genetic code is stored, .i.e. between the chloroplast and the cell’s nucleus.

However, in developing this understanding, the team has stated that further research is to fully understand the complex relationship between the chloroplast and the cells’ nucleus.

The team believes that fertilizer management may play a key role.

If we take actions that don’t consider how the nutrients interact with each other, we potentially create conditions that set plants up to fail. It’s critical that we correct this thinking moving forward for the benefit of food production worldwide.

Hatem Rouached, Lead Author and Assistant Professor at MSU

As the global climate continues to come under scrutiny and given the potential impact climate change could have on agriculture and food production, new fertilizer strategies could address some of the issues surrounding food security.

Therefore, understanding the relationship between plants and nutrients in fine detail, such as the pH values of soil and fertilizers, could support and advance agricultural practices in a world faced with shifting environmental conditions.

References and Further Reading

Nam, H. and Shahzad, Z., et al., (2021) Interdependent iron and phosphorus availability controls photosynthesis through retrograde signaling. Nature Communications, [online] 12(1). Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-27548-2

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.