Reviewed by Mila PereraSep 15 2022

Recent efforts have concentrated on ice-sheet geometry, fracture, and surface melting — processes that could start or accelerate ice-sheet mass loss — to better understand how melting Antarctic ice will affect the planet’s oceans.

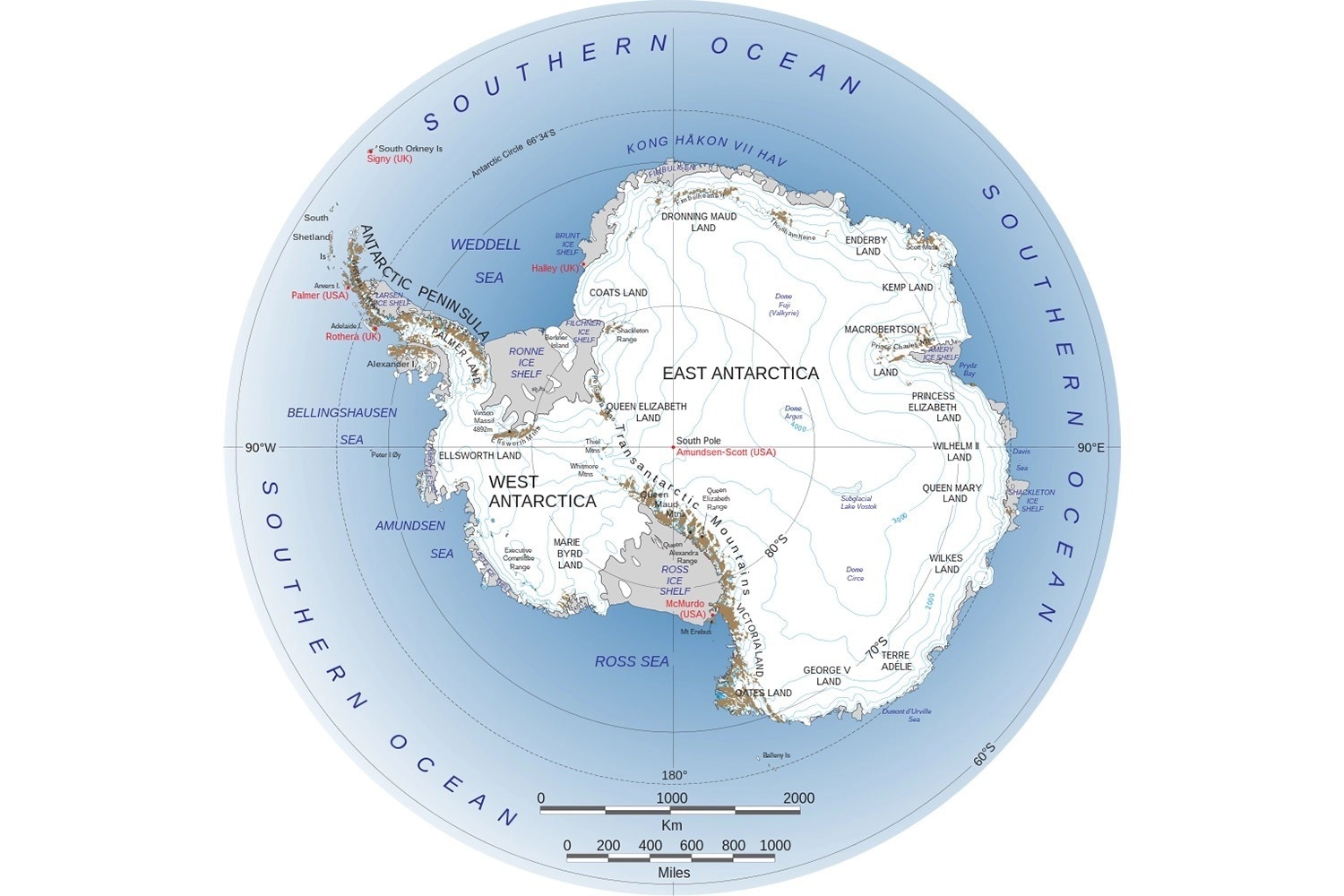

Map of Antarctica. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The bed's thawing, or basal thaw, at the interface of the land and the miles-thick ice sheet above it has been identified as another mechanism that could majorly impact the future of the ice sheet.

The new research indicates regions that, when thawed, may rival some of the biggest drivers of sea-level rises, such as the Thwaites Glacier. Antarctica is around the size of the United States, and its vulnerable areas cover a section larger than California. The study was released in the journal Nature Communications on September 14th, 2022.

You can’t necessarily assume that everywhere that’s currently frozen will stay frozen. These regions may be under-appreciated potential contributors.

Dustin Schroeder, Study Senior Author and Associate Professor, Geophysics, Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability

Unusual Suspects

Recent theoretical work suggesting that basal thaw could occur over short time scales served as the foundation for the simulations. The study’s co-authors explored theories about whether the start of such a thaw could result in major ice loss within a century using numerical ice sheet models.

They discovered that thawing caused a mass loss in parts of the ice sheet that are not typically linked to instability and contributions to sea level at that time scale.

There really has been little to no continental-wide work that looks at the onset of thawing—that transition from frozen ice to ice at the melting point, where a little bit of water at the bed can cause the ice to slide. We were interested in learning how big an effect thawing could have and what regions of the ice sheet were potentially most susceptible.

Eliza Dawson, Study Lead Author and Ph.D. Student, Geophysics, Stanford University

The authors examined changes in friction brought on by the ice sheet moving to estimate temperature changes at Antarctica’s base.

The simulations showed that the Enderby-Kemp and George V Land regions in East Antarctica, currently thought to be more stable than West Antarctica, would be more vulnerable to thawing at their beds.

They also emphasized that the Wilkes Basin in George V Land has huge potential to contribute significantly to sea level rise in the event of thawing; this feature is comparable in size to the fast-changing and likely unstable Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica.

Schroeder, an associate professor of electrical engineering, adds, “The whole community is really focusing on Thwaites right now. But some of the regions that are the usual suspects for big, impactful changes aren’t the most provocative and impactful areas in this study.”

Temperature Matters

The ice sheet is poorly understood due to its position in Antarctica and its harsh climate. Even less is known about the land hidden below its frozen façade.

Measuring the bed is a massive effort in these remote places—we have the technology to do it, but you really need to pick the spot, and sometimes it takes years, and field camps, and special equipment to go do that. It’s difficult and expensive.

Dustin Schroeder, Study Senior Author and Associate Professor, Geophysics, Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability

The investigators used the physics of how ice slides — how temperature variations affect how the ice sheet flows and changes through time — to fill in knowledge gaps. The authors intend to create and use radar-based analysis techniques in subsequent work to investigate the temperature of the ice sheet bed in these crucial regions.

Schroeder details, “You need to know the regions where it matters, and that’s the transformative contribution of Eliza’s paper. It asks these broad questions: Does this matter? And if it matters, where? We hope this approach gives the community some priorities into where to look and why, and to avoid going down blind alleys.”

Sleeping Giants

In the potentially vulnerable regions, scientists do not yet know what factors are most likely to cause thawing at the bed. Antarctica's frequently changing ocean conditions could be one potential reason.

Schroeder explains, “Warm ocean water does not necessarily reach these East Antarctica regions as it does in parts of West Antarctica, but it’s nearby, so there’s potential that could change. When you consider the recent theoretical work showing that thermal processes at the bed can be easy to activate — even spontaneous — it makes near-term thawing of the ice-sheet bed seem like a far easier switch to flip than we’d thought.”

The study demonstrates how measuring, comprehending, and modeling the temperature at the base of ice sheets is critical for understanding the future since the biggest source of uncertainty in projections for sea-level rise is processes that can change the behavior of sizable ice sheets.

Dawson concludes, “Follow-on work will be needed to take a closer look at these regions that this paper identified. Showing that thawing at the bed can result in mass loss from the ice sheet is a process that the community needs to understand and really start looking at—especially in these potentially vulnerable areas.”

Journal Reference

Dawson, E. J., et al. (2022) Ice mass loss sensitivity to the Antarctic ice sheet basal thermal state. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32632-2.