Salt marshes, which are key habitats threatened by accelerated sea-level rise, may persist despite increased water levels, according to a group of scientists guided by Brian Yellen, Research Professor of Earth, Geographic, and Climate Sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

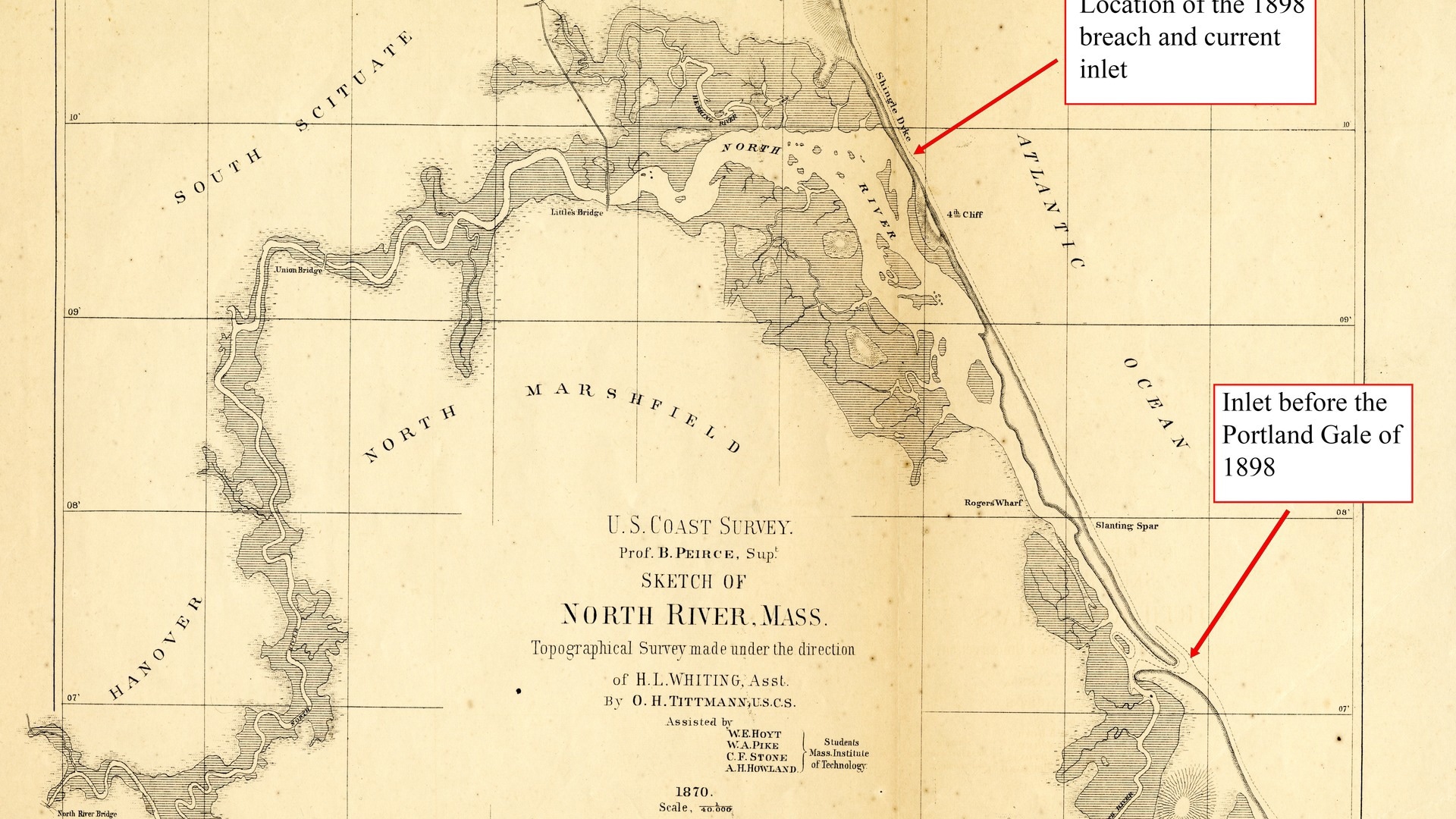

The Portland Gale of 1898 moved the inlet of the North-South Rivers Estuary approximately three-and-a-half miles northwest of its previous location. Image Credit: UMass Amherst

The Portland Gale of 1898 moved the inlet of the North-South Rivers Estuary approximately three-and-a-half miles northwest of its previous location. Image Credit: UMass Amherst

The fundamental factor determining whether salt marshes perish or survive is not water, but sediment. The study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface.

Yellen and his co-workers traced their findings back to 1898, when the Portland Gale, a vicious Nor’easter, devastated the Massachusetts coast with hurricane-force winds, buckets of rain, and a 10-foot storm surge, remaking the North-South Rivers Estuary in Scituate, just south of Boston.

Before 1898, the North River took a sharp south-eastern turn on its route to the Atlantic Ocean, flowing behind a barrier beach for nearly three and a half miles before joining the South River at today’s popular Rexhame Beach, where both rivers eventually exited to the sea.

The Portland Gale, which came in late November, made a hole in the northern end of the barrier beach, cutting the North River’s route by three and a half miles. High tides in the newly shortened tidal river instantly rose by at least a foot—the type of sea-level rise predicted by scientists for the end of the century.

It was a terrible storm. But it provided us with the rarest of things—a real-world, long-term experiment showing us how salt marshes, like those along the North River Estuary, may respond to rapid sea level rise in the coming years.

Brian Yellen, Research Professor, Earth, Geographic, and Climate Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst

One of the several risks posed by rising oceans is the loss of salt marshes, which not only provide important habitats for migrating birds and juvenile fish stocks but also provide a range of important ecosystem services like defending coastlines from storm damage and filtering contaminants from runoff. And, unlike popular belief, the unexpected flooding of Scituate’s marshes was not disastrous.

The salt marsh is thriving. Salt marshes are made up of three things. Water, plants, and sediment.

Brian Yellen, Research Professor, Earth, Geographic, and Climate Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst

The group speculates that the high coastal bluffs bordering the coast near the North River Estuary can provide an ample supply of sediment as they gradually erode into the ocean, allowing the salt marshes to bounce back and acclimate to their changing environment even in catastrophic conditions like the Portland Gale.

Sediment, on the other hand, has long been regarded as a problem, particularly in estuaries. Sediment clogs shipping lanes and creates mudflats, which many people dislike. Dredging deep channels and hauling the scooped-up material far out to sea has long been the normal practice. Upstream dams have also restricted the flow of sediment from the interior to the coast.

We treat sediment as if it’s trash, but it’s really treasure. It makes up the beaches that we love to play on, and the salt marshes that support both endangered birds and commercially important fish stocks. It’s time to stop treating sediment like waste.

Brian Yellen, Research Professor, Earth, Geographic, and Climate Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Yellen is quick to note that he is not recommending the elimination of dredging and coastal navigation, nor the removal of all dams, but rather that when dredging is required, a compensatory re-infusion of sediment into the impacted estuary system is required.

The study was funded by the US Geological Survey and the Department of the Interior’s Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center. Yellen and his associates have already collaborated with a dozen public stakeholders from all New England states to further research how to best address the threats posed by climate change to New England’s shoreline.

Journal Reference:

Yellen, B., et al. (2022) Salt Marsh Response to Inlet Switch-Induced Increases in Tidal Inundation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface. doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006815.