The University of Notre Dame scientists are expanding their list of consumer products containing PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), a toxic class of fluorine compounds called “forever chemicals.”

Image Credit: University of Notre Dame

Fluorinated high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic containers—used mostly for household cleaners, pesticides, personal care products, and presumably food packaging—tested positive for PFAS in a new study published in Environmental Science and Technology Letters.

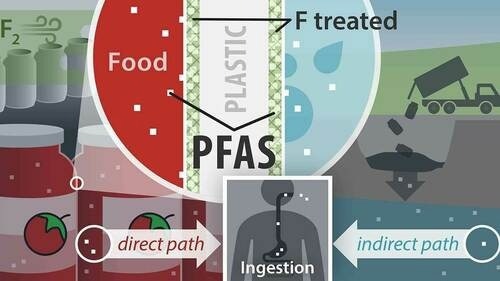

Following an EPA report demonstrating that this type of container did contribute high levels of PFAS to a pesticide, this study demonstrates the first measurement of the potential of PFAS to leach from containers into food and the effect of temperature on the leaching process.

The PFAS were also found to be capable of moving from fluorinated containers into food, resulting in a direct route of greater exposure to the toxic chemicals, which have been linked to a variety of health problems such as kidney, prostate, and testicular cancers, immunotoxicity, low birth weight, and thyroid disease.

Not only did we measure significant concentrations of PFAS in these containers, we can estimate the PFAS that were leaching off creating a direct path of exposure.

Graham Peaslee, Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Notre Dame

It is indeed worth noting that these containers are not designed for food storage, and there is nothing stopping them from being used for that purpose. Even though not all HDPE plastic is fluorinated, the researchers noted that it is frequently impossible for a consumer to tell whether a container has been fluorinated.

Indeed, Peaslee added, if pesticides are stored in these containers and used on agricultural crops, these same PFAS will enter human food sources.

The EPA declared its PFAS Strategic Roadmap in 2021, agreeing to act in response to widespread PFAS exposure. The plan includes gaining a better comprehension of the health and environmental effects of PFAS exposure, restricting further contamination of land, air, and water, and acknowledging the need for PFAS cleanup already in the environment.

PFAS is often used in connection with stain- or water-resistant products. Peaslee and graduate student Heather Whitehead examined HDPE containers treated with fluorine to produce a thin layer of fluoropolymer as a means of imparting chemical resistance and improving container performance over long storage periods for the study.

While these materials typically remain in the container wall, the manufacturing process can produce many smaller PFAS molecules that are not polymers. Experiments were designed to test these chemicals’ ability to migrate from the container to various foods and solvents samples.

The containers tested positive for PFAS at parts-per-billion levels, which could migrate into solvents and food matrices in as little as one week.

We measured concentrations of PFOA that significantly exceeded the limit set by the EPA’s 2022 Health Advisory Limits. Now, consider that not only do we know that the chemicals are migrating into the substances stored in them, but that the containers themselves work their way back into the environment through landfills. PFAS doesn’t biodegrade. It doesn’t go away. Once these chemicals are used, they get into the groundwater, they get into our biological systems, and they cause significant health problems.

Graham Peaslee, Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Notre Dame

Peaslee and Whitehead evaluated PFAS levels in olive oil, ketchup, and mayonnaise after seven days of encountering fluorinated containers at different temperatures. The study estimates that enough PFAS could be consumed through food stored in the containers to pose a serious risk of exposure based on the amounts found in the different food samples.

Journal Reference:

Whitehead, H. D. & Peaslee, G. F. (2023) Directly Fluorinated Containers as a Source of Perfluoroalkyl Carboxylic Acids. Environmental Science and Technology Letters. doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.3c00083.