A group of researchers from the University of Oklahoma has published a perspective article in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences promoting convergent research that combines the fields of biogeography and behavioral ecology to respond more quickly to climate change and biodiversity loss challenges.

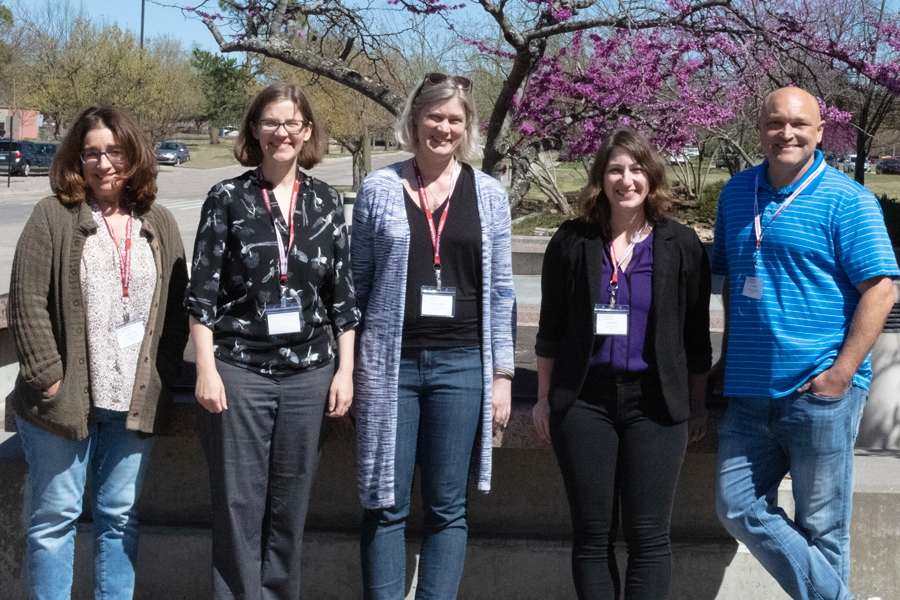

University of Oklahoma researchers (pictured from left) Ashlee Rowe, Hayley Lanier, Katharine Marske, Laura Stein, and Cameron Siler authored a perspective article advocating for convergent research that integrates the fields of biogeography and behavioral ecology to more rapidly respond to challenges associated with climate change and biodiversity loss. Image Credit: University of Oklahoma

University of Oklahoma researchers (pictured from left) Ashlee Rowe, Hayley Lanier, Katharine Marske, Laura Stein, and Cameron Siler authored a perspective article advocating for convergent research that integrates the fields of biogeography and behavioral ecology to more rapidly respond to challenges associated with climate change and biodiversity loss. Image Credit: University of Oklahoma

While climate change news dominates headlines, the problem of biodiversity loss has received less attention. The authors argue in their study that “identifying solutions that prevent large-scale extinction requires addressing critical questions about biodiversity dynamics that—despite widespread interest—have been challenging to answer thus far.”

From microbes that sustain soil health to fish that humans consume and forests that clean water to pollination, lumber, and medicine, ecosystems and the diverse plants and animals that inhabit them are vital for the health of the planet and the survival of humanity.

The ways that we respond to climate change also have a big impact on outcomes for biodiversity—which is also a critical part of how the global climate system works. Climate change is a major threat to biodiversity, but it’s not the only threat. We also have habitat loss and degradation, direct overharvest of some species and so forth, so it’s also its own unique crisis that needs to be considered on equal footing.

Katharine Marske PhD, Study Co-Author and Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, Dodge Family College of Arts and Sciences

“Historically in Oklahoma, we can point to cases where we have rapidly removed or changed natural habitats, such as the Dust Bowl. That was a case where we came through and stripped out a lot of the existing natural systems that do things to hold onto the soil and create nutrients, and that was sort of one small example,” says said co-author Hayler Lanier, PhD, Assistant Curator of Mammalogy at the Sam Noble Museum and an Assistant Professor of Biology.

“As we move into the future, we need to think about what sort of world we want to live in, and it is definitely one where we have these sorts of ecosystem services,” added Hayler Lanier.

The researchers argued that by combining the fields of biogeography, or the study of how and why biological diversity differs across the Earth, and behavioral ecology, or the study of the evolution of behavior in response to ecological pressures, researchers would be able to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how to leverage “existing biodiversity knowledge into predictive frameworks for how biodiversity will respond to environmental change, and where habitat conservation can be most effective.”

This interdisciplinary connection between behavioral ecologists and scientists who study biogeography has not been linked well to date. I think in many cases, biogeographers are not thinking about day-to-day activities of animals as much as behavioral ecologists are, and behavioral ecologists are not necessarily considering differences and overlaps in both current and historical ranges and how behaviors have been shaped by past geographic events that might help predict where they will be in the future.

Laura Stein PhD, Study Co-Author and Assistant Professor, Biology, University of Oklahoma

Laura Stein adds, “And so, by combining these two fields, we can get a much broader picture of what we can do now and what is important for protecting biodiversity into the future.”

The article's authors led a pilot of such integrative efforts at the University of Oklahoma, funded by the National Science Foundation.

We, in the Department of Biology, together with the Sam Noble Museum, carried out a series of cluster hires over the last five years aimed strategically at bringing together integrative researchers with the capacity to think beyond these typically isolated fields, and what’s exciting is this work is a culmination of the success of that early effort to bring scientists like this together at OU.

Cameron Siler PhD, Study Co-Author and Associate Professor, Biology, University of Oklahoma

Cameron Siler is also the associate curator of herpetology at the Sam Noble Museum.

Lanier outlined their approach as hopeful. Biodiversity loss and climate change are vast, complex, and difficult problems to address. “What we’re trying to do is to harness a lot of information that we already have as scientific and conservation communities and bring it together in new ways to very quickly answer some of these questions.”

Marske agreed and added, “The scope of the challenges that society faces require integration, so providing opportunities for this across biology, and amongst all disciplines, increases your chances to bring people together and talk about novel solutions. The more people you can have at that table, the better.”

Journal Reference

Marske, K. A., et al. (2023). Integrating biogeography and behavioral ecology to rapidly address biodiversity loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2110866120.