Deteriorating habitat conditions as a result of climate change are causing chaos with the timing of bird migration. A new study shows that birds can compensate for these changes by delaying the start of spring migration and completing their journies faster.

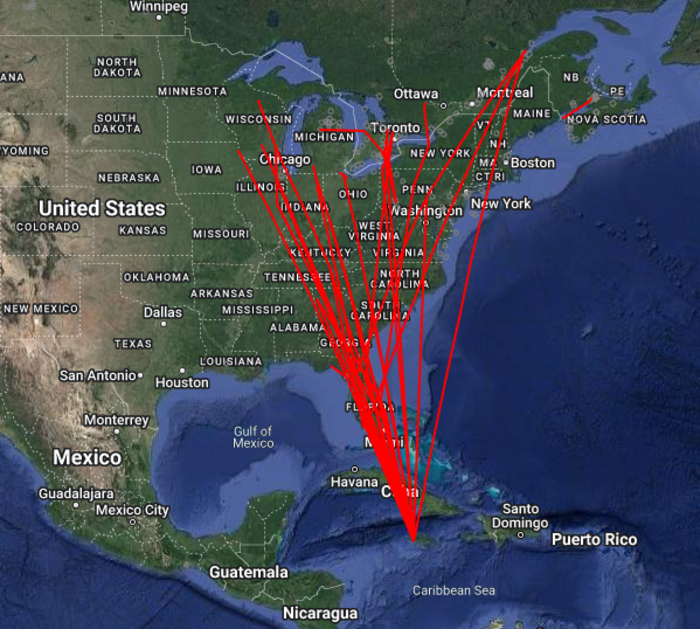

Spring migration routes for American Redstarts wintering in Jamaica. Image Credit: Motus Wildlife Tracking System.

However, the method comes at a cost: a decrease in overall survival. Scientists from Cornell University, the University of Maryland, and Georgetown University published their findings in the journal Ecology.

We found that our study species, the American Redstart, can migrate up to 43% faster to reach its breeding grounds after delaying departure from wintering grounds in Jamaica by as much as 10 days. But increased migration speed also led to a drop of more than 6% in their overall survival rate.

Bryant Dossman, Study Lead Author, Cornell University

Dossman led the research as a graduate student at Cornell and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Georgetown.

Strategies for speeding up migration can include flying faster and stopping for fewer or shorter periods of time to refuel along the way. Though faster migration helps compensate for delayed departures, it cannot completely compensate for lost time.

Dossman claims that with a 10-day delay, individuals can regain around 60% of the lost time, but this still means that they arrive late to the breeding grounds.

Jamaica has become increasingly dry in recent decades and that translates into fewer insects, the mainstay of the redstart diet. It now takes the birds longer to get into conditions for the hardships of migration, especially if they are coming from lesser-quality habitats. At the same time, plants are greening and insects are appearing earlier on breeding grounds as a result of climate change.

On average, migratory songbirds only live a year or two, so keeping to a tight schedule is vital. They’re only going to get one or two chances to breed. Longer lived birds are less likely to take the risk of speeding up migrations because they have more chances throughout their lives to breed and pass on their genes.

Bryant Dossman, Study Lead Author, Cornell University

The research is based on 33 years of American Redstart migration departure data from Jamaica’s Fort Hill Nature Preserve. The study site is overseen by senior co-author Peter Marra, Director of the Earth Commons at Georgetown University’s Institute for Environment and Sustainability.

Using historical data, automated radio tracking, and light-level tags, researchers compared the redstarts’ anticipated departure date to their actual departure date in subsequent years to determine how it had changed.

The behavioral shifts documented in this research remind us that the manner in which climate change affects animals can be subtle and, in some cases, able to be detected only after long term study.

Amanda Rodewald, Study Co-Author, Garvin Professor and Senior Director, Center for Avian Population Studies, Cornell University

“Understanding how animals can compensate is an important part of understanding where the impacts of climate change will play out. In this case, we may not lose a species entirely, but it is possible that populations of some species may go extinct locally due to climate change,” adds Marra.

What happens on the redstart wintering grounds carries over into the breeding season. Though the redstart population is stable and increasing in much of its breeding range, detailed eBird Trend maps show the species is in fact on the decline in the northeastern United States and southern Quebec, Canada.

Dossman concludes, “The good news is that birds are able to respond to changes in their environment. They have some flexibility and variation in their behaviors to begin with, but the question is, have they reached the limit of their ability to respond to climate change?”

Journal Reference

Dossman, B. C., et al. (2023). Migratory birds with delayed spring departure migrate faster but pay the costs. Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3938.