Dec 14 2008

A few years ago, scientists at the University of Idaho discovered birth control pills not only control the human population, but also can devastate rainbow trout populations. Now they may know why.

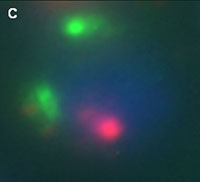

This photo shows the nucleus of a rainbow trout sperm. The red mark is a sex chromosome and the green is chromosome 20. This particular nucleus has an extra green spot – an extra chromosome 20. Genetic mutations such as these are caused by synthetic estrogens in the environment and may be one reason why embryos created from the mutated sperm have a low survival rate

This photo shows the nucleus of a rainbow trout sperm. The red mark is a sex chromosome and the green is chromosome 20. This particular nucleus has an extra green spot – an extra chromosome 20. Genetic mutations such as these are caused by synthetic estrogens in the environment and may be one reason why embryos created from the mutated sperm have a low survival rate

James Nagler, professor of biological sciences, recently discovered that 17α-ethynylestradiol – an active chemical in birth control pills – causes cells in rainbow trout to have an abnormal number of chromosomes. This condition, known as aneuploidy, is often found in cancer cells, causes Down’s syndrome in humans, and may be why many embryos fathered by exposed specimens die within three weeks.

The results, coauthored with Kim Brown and Joe Cloud from the University of Idaho, and Irvin Schultz of Battelle Pacific Northwest National Laboratory – Marine Science Laboratory were published in this week’s edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The bottom line is that aneuploidy is abnormal and highly undesirable,” said Nagler. “I believe this compound is causing elevated levels of sperm aneuploidy, which in turn is greatly reducing the embryonic survival rate in the fish it affects.”

Nagler exposed male rainbow trout to the chemical and tested their sperm for abnormal chromosome levels. He then fertilized eggs from unexposed females with the affected semen and compared the resulting offspring’s survival rate with a control group that was not exposed to the synthetic estrogen.

The results showed that while offspring sired by healthy male and female fish enjoyed a three-week survival rate of more than 95 percent, only 40 to 60 percent of the young trout from the affected semen survived. Additionally, the abnormal chromosomal levels were passed on to some of the offspring.

The chemical 17α-ethynylestradiol is a synthetic estrogen commonly used in human birth control pills and is released into the environment through urination. The compound is difficult to remove in waste treatment plants, and very few plants are capable of removing the chemical before releasing the water back into the environment.

“The concentrations we tested are not found everywhere,” said Nagler. “But there are definitely many places in the world containing levels close to – if not exceeding – the concentration that we tested.”

There are other synthetic estrogens released into the environment every day besides 17α-ethynylestradiol. Similar chemicals are found everywhere from detergents to pesticides and cause many more problems than chromosome abnormalities. For example, the pesticide DDT – a weak estrogen – caused the egg shells of bald eagles to be thin and weak, contributing to their declining numbers during the mid-1900s.

Nagler’s research results raise many questions on the levels of synthetic estrogens in surface water across the country and how they might be affecting all animals using the water, including humans.

“Nobody can say that these compounds are the main cause of salmon decline because it’s a very complex issue and there are many, many factors involved,” said Nagler. “But it can’t help.”