Mar 9 2009

A University of Arkansas researcher studying the way caves "breathe" is providing new insights into the process by which scientists study paleoclimates.

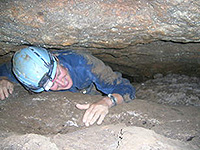

Erik Pollock of the Stable Isotope Laboratory at the University of Arkansas, climbs into tight spaces to study carbon dioxide cycling in caves. Seasonal differences can provide clues to paleoclimate proxies

Erik Pollock of the Stable Isotope Laboratory at the University of Arkansas, climbs into tight spaces to study carbon dioxide cycling in caves. Seasonal differences can provide clues to paleoclimate proxies

Katherine Knierim, a graduate student at the University of Arkansas, together with Phil Hays of the geosciences department and the U.S. Geological Survey and Erik Pollock of the University of Arkansas Stable Isotope Laboratory, are conducting close examinations of carbon cycling in an Ozark cave. Caves “breathe” in the sense that air flows in and out as air pressure changes.

The researchers have found that carbon dioxide pressures vary with external temperatures and ground cover, indicating a possible link between the carbon found in rock formations in the caves and seasonal changes. They presented their findings at a recent meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

The movement of carbon in cave systems is controlled by the concentration of carbon dioxide. When conditions are right, this carbon can be deposited as layers in stalagmites, stalactites and soda straws. These layers resemble the rings found in trees, except that they can date back millions of years, hold information about cave conditions.

“People have been using these formations as paleoclimate records,” Hays said. However, researchers make an assumption when they do so.

“The problem is that you have to assume you are getting even carbon and oxygen isotope exchange,” Knierim said. Isotopes, or atoms of the same type but with slightly different weights, are found in plants, animals, organic matter and rocks. Different types of material have unique “signatures,” or proportions of a particular atom at a particular atomic weight.

By looking at carbon isotope ratios in cave topsoils, the cave atmosphere and the stream within the cave, Knierim and her colleagues will be able to determine the different contributions of carbon sources to the formations. This will help scientists develop more accurate paleoclimate conditions from cave formations.

A greater knowledge of how carbon cycles through cave systems also will help scientists develop better methods for watershed management.

The researchers are in the geosciences department of the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences.