Jun 30 2009

Rising carbon dioxide levels in the ocean have been shown to adversely affect shell-forming creatures and corals, and now a new study by researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego has shown for the first time that CO2 can impact a fundamental bodily structure in fish.

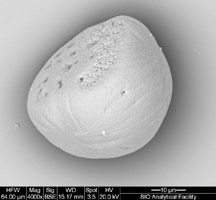

side view of an otolith imaged with a scanning electron microscope. The top is smooth (oriented downward) and the bottom is pitted. The holes are approximately 1-2 microns in diameter

side view of an otolith imaged with a scanning electron microscope. The top is smooth (oriented downward) and the bottom is pitted. The holes are approximately 1-2 microns in diameter

A brief paper published in the June 26 issue of the journal Science describes experiments in which fish that were exposed to high levels of carbon dioxide experienced abnormally large growth in their otoliths, or ear bones. Otoliths serve a vital function in fish by helping them sense orientation and acceleration.

The researchers had hypothesized that otoliths in young white seabass growing in waters with elevated carbon dioxide would grow more slowly than a comparable group growing in seawater with normal CO2 levels. They were surprised to discover the reverse, finding “significantly larger” otoliths in fish developing in high-CO2 water.

The fish in high-CO2 water were not larger in overall size, only the otoliths grew demonstrably bigger.

“At this point one doesn’t know what the effects are in terms of anything damaging to the behavior or the survival of the fish with larger otoliths,” said David Checkley, a Scripps Oceanography professor and lead author of the new study. “The assumption is that anything that departs significantly from normality is an abnormality and abnormalities at least have the potential for having deleterious effects.”

With carbon dioxide levels rising due to human activities, particularly fossil fuel burning, resulting in both increased ocean CO2 and ocean acidification, the researchers intend to broaden their studies to examine specific areas, such as determining whether the otolith growth abnormality exists in fish other than white seabass; locating the physical mechanism that causes the enhanced otolith growth; and assessing whether the larger otoliths have a functional effect on the survival and the behavior of the fish.

“Number three is the big one,” said Checkley. “If fish can do just fine or better with larger otoliths then there’s no great concern. But fish have evolved to have their bodies the way they are. The assumption is that if you tweak them in a certain way it’s going to change the dynamics of how the otolith helps the fish stay upright, navigate and survive.”

In addition to serving in orientation and acceleration, otoliths help reveal physical characteristics of fish. Because otoliths grow in onion-like layers, scientists use otoliths to determine the age of fish, counting the increments similar to tree-ring dating.

Coauthors of the paper include Andrew Dickson, John Radich and Rebecca Asch of Scripps Oceanography; Motomitsu Takahashi of the Seikai National Fisheries Research Institute in Nagasaki, Japan; and Nadine Eisenkolb of the University of Southern California.

The research was supported by the Academic Senate of UC San Diego.