Sep 11 2009

CSIRO researchers have discovered that micro-organisms that help break down contaminants under the soil can actually get too hot for their own good.

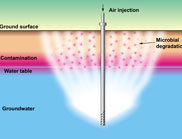

Schematic showing how biosparging enhances the microbial degradation of contaminants. Photo by: CSIRO

Schematic showing how biosparging enhances the microbial degradation of contaminants. Photo by: CSIRO

While investigating ways of cleaning up groundwater contamination, scientists examined how microbes break down contaminants under the soil’s surface and found that subsurface temperatures associated with microbial degradation can become too hot for the microbes to grow and consume the groundwater contaminants.

This can slow down the clean up of the groundwater and even continue the spread of contamination.

The new findings mean that researchers now have to rethink the way groundwater remediation systems are designed.

CSIRO Water for a Healthy Country Flagship scientist Mr Colin Johnston, who is based in Perth, Western Australia, said the researchers were investigating how temperatures below the soil’s surface could be used as an indicator of the microbial degradation process associated with biosparging.

Biosparging is a technique that injects air into polluted groundwater to enhance the degradation of contaminants.

The contaminants are ‘food’ to the microbes and the oxygen in the air helps the microbes unlock the energy in the food so that they metabolise and grow, consuming more contaminants and stopping the spread of the contamination.

“Observations of diesel fuel contamination showed that, at 3.5 metres below the ground surface, temperatures reached as high as 47 °C,” Mr Johnston said.

“This is close to the 52 °C maximum temperature tolerated by the community of micro-organisms that naturally live in the soil at this depth and within the range where the growth of the community was suppressed.”

The growth of the soil’s micro-organism community can also be helped by adding nutrients.

However computer modelling confirmed that any attempts to further increase degradation of the contamination through the addition of nutrients had the potential to raise temperatures above the maximum for growth.

“Although increasing the flow of air would reduce temperatures and overcome these limitations a fine balance needs to be struck as the injected air can generate hazardous vapours that overwhelm the micro-organisms leading to unwanted atmospheric emissions at the ground surface,” Mr Johnston said.

“This would be particularly so for highly volatile compounds such as gasoline.

“It appears that prudent manipulation of operating conditions and appropriate timing of nutrient addition may help limit temperature increases.”

Mr Johnston said further research was required to better understand the thermal properties in the subsurface as well as the seasonal effects of rainfall infiltration and surface soil heating.