Jan 22 2018

With the aim to develop an alternative to the elephant tusk ivory used to build piano keys, John Wesley Hyatt patented the first industrial plastic in 1869. This early plastic also ignited a revolution in the way people regarded manufacturing: what if we didn't need to be limited to just the materials nature had to provide?

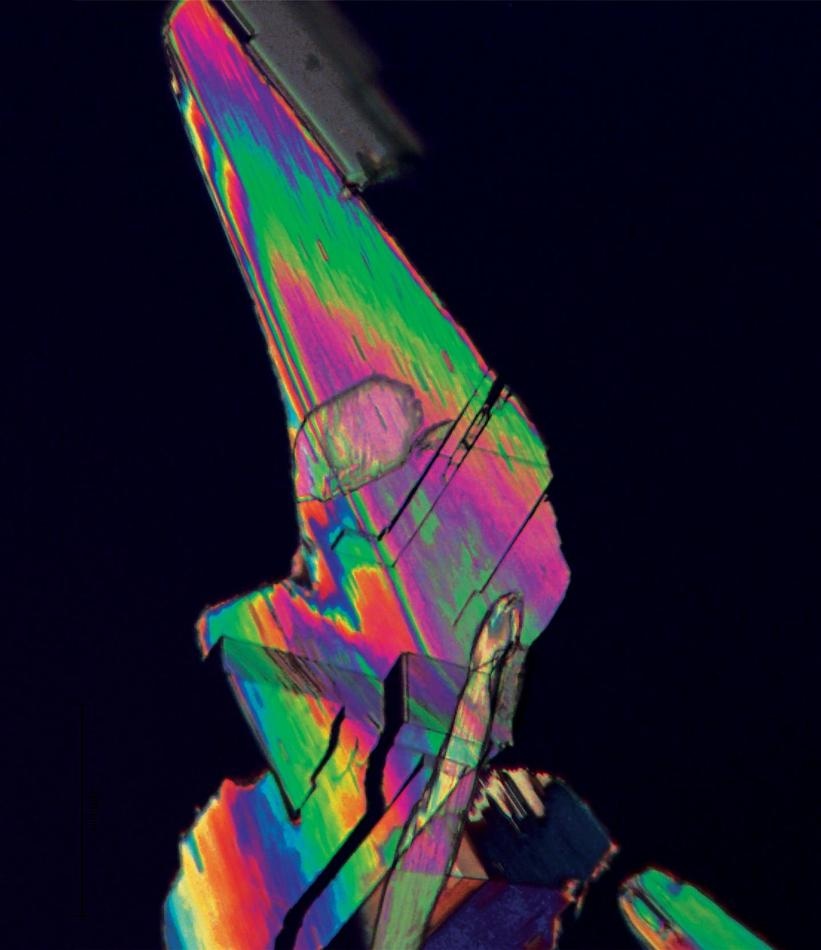

This is a crystal of furandicarboxylic acid, or FDCA, a plastic precursor created with biomass instead of petroleum. (Image credit: UW-Madison/Ali Hussain Motagamwala/James Runde)

This is a crystal of furandicarboxylic acid, or FDCA, a plastic precursor created with biomass instead of petroleum. (Image credit: UW-Madison/Ali Hussain Motagamwala/James Runde)

More than a century later, plastics are used a lot in everyday life. But these plastics are mostly derived from petroleum, contributing to a dependence on fossil fuels and driving destructive greenhouse gas emissions. To alter that, Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) researchers are attempting to take the flexible nature of plastic in another direction, forming new and renewable ways of producing plastics from biomass.

Using a plant-derived solvent known as gamma-Valerolactone (GVL), University of Wisconsin-Madison Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering James Dumesic and his team have formulated an economical and high-yielding way of creating furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA). As one of 12 chemicals the U.S. Department of Energy terms as 'critical', FDCA is an essential precursor to a renewable plastic known as polyethylene furanoate (PEF) as well as to many polyurethanes and polyesters.

The team published their findings in the January 19, 2018 issue of Science Advances.

As the bio-based substitute for polyethylene terephthalate (PET), it's extensively used, petroleum-derived counterpart PEF is full of potential. PET presently has a market demand of nearly 1.5 billion tons annually and Coca-Cola, Nike, H.J. Heinz, Ford Motors, and Procter & Gamble have all committed to creating a sustainably sourced, 100% plant-based PET for their footwear, packaging, bottles and apparel. PEF's potential to enter into that sizeable market however, has been hindered by the high cost of making FDCA.

"Until now, FDCA has had a very low solubility in practically any solvent you make it in," says Ali Hussain Motagamwala, a UW-Madison graduate student in chemical and biological engineering and co-author of the study. "You have to use a lot of solvent to get a small amount of FDCA, and you end up with high separation costs and undesirable waste products."

Motagamwala and colleagues' new process starts with fructose, which they convert during a two-step process to FDCA; in a solvent system made up of one part GVL and one part water. The final result is a high yield of FDCA that easily separates from the solvent as a white powder when cooled.

Using the GVL solvent solves most of the problems with the production of FDCA. Sugars and FDCA are both highly soluble in this solvent, you get high yields, and you can easily separate and recycle the solvent.

Hussain Motagamwala

Other attributes of the process add to its robust economics. The system does not require expensive mineral acids for catalysis, does not form waste salts and can separate out the FDCA crystals from the solvent by just cooling the reaction system.

The team's techno-economic analysis proposes that the process could presently create FDCA at a minimum selling price of $1,490 per ton. With enhancements, including reducing the cost of feedstock and decreasing the reaction time, the price could touch $1,310 per ton, which would make their FDCA cost-competitive with certain fossil fuel-derived plastic precursors.

We think this is the streamlined and inexpensive approach to making FDCA that many people in the plastics industry have been waiting for. Our hope is that this research opens the door even further to cost-competitive renewable plastics.

James Dumesic, Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering

The Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation is aiming to license GVL technology for application in bioplastics production.