Apr 7 2021

Global warming can decrease crop yields by one-third by 2050. Scientists from the University of California, Riverside have discovered a gene that could reverse this effect.

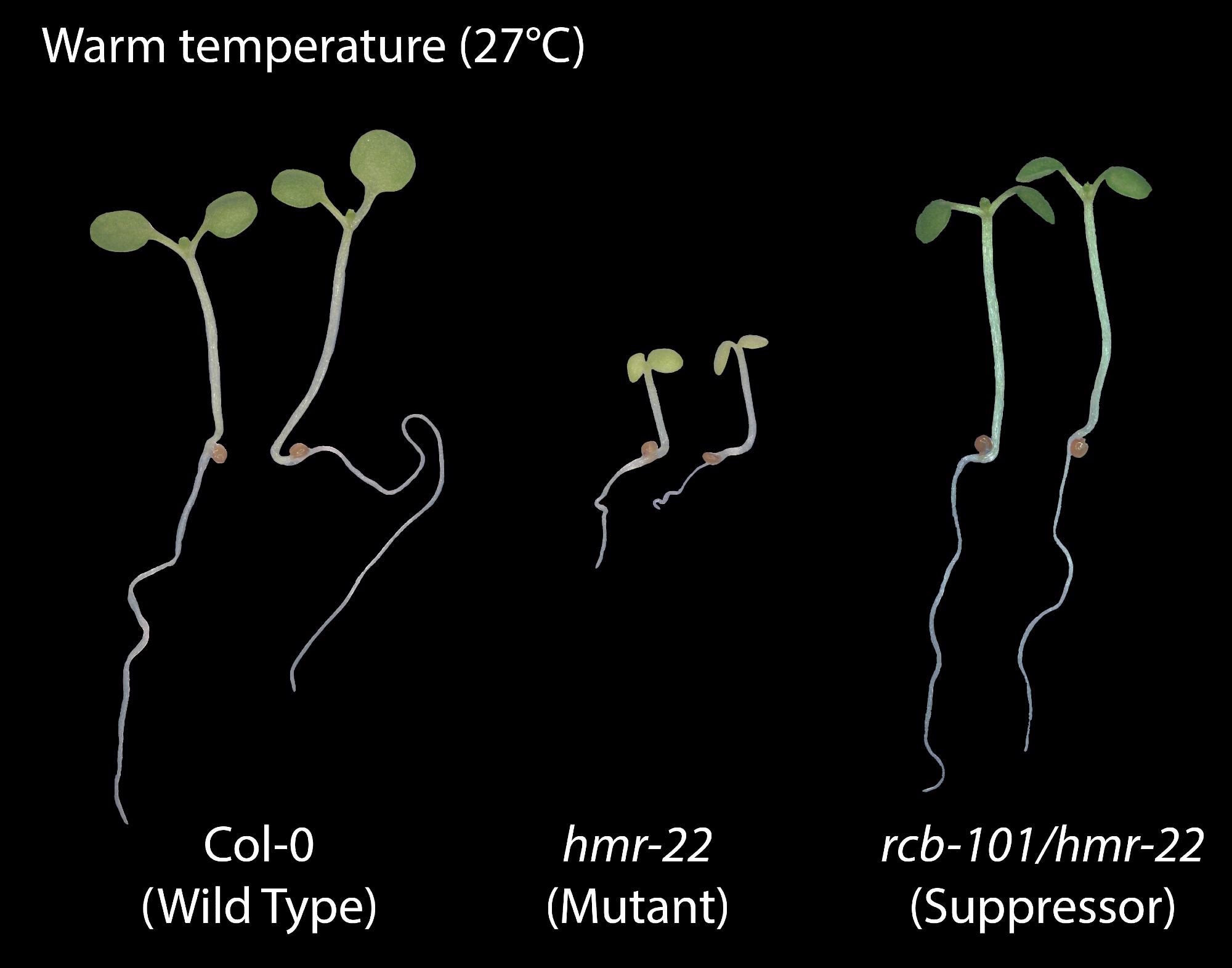

Drastic differences in mutant Arabidopsis seedlings grown at warm temperatures. Image Credit: Meng Chen/UCR.

Drastic differences in mutant Arabidopsis seedlings grown at warm temperatures. Image Credit: Meng Chen/UCR.

The plants get an indication from warmer temperatures that summer is about to begin. They expect less water and flower earlier, and hence there is a shortage of energy to produce more seeds. This leads to a decrease in crop yields. This is cause for concern because the world’s population is anticipated to inflate to 10 billion, having much less food to eat.

We need plants that can endure warmer temperatures, have a longer time to flower and a longer growth period. But, to be able to modify plants’ temperature responses, you first have to understand how they work. So, that’s why identifying this gene that enables heat response is so important.

Meng Chen, Plant Sciences Professor, University of California, Riverside

The study by Chen and his collaborators to identify the heat-sensing gene was reported this week in the Nature Communications journal.

It is the second gene they have discovered to play a role in temperature sensing.

Two years ago, they found the first gene, known as HEMERA. They then performed an experiment to observe whether they could determine other genes that are responsible for regulating the process of temperature sensing.

Normally, plants respond to changes of even a few degrees in weather. To perform this experiment, the team started with a mutant Arabidopsis plant that is entirely insensitive to temperature, and they altered it to become reactive once again.

Investigation of the genes of this twice-mutated plant disclosed the new gene, RCB, whose products function closely with HEMERA to stabilize the heat-sensing function. “If you knock out either gene, your plant is no longer sensitive to temperature,” stated Chen.

Both RCB and HEMERA are needed to control the abundance of a family of master gene regulators that provide several functions, reacting to temperature and light, as well as making plants turn green. Such proteins are circulated to two distinct parts of plant cells—the nucleus and organelles known as chloroplasts.

Chen feels that in the future, his laboratory will work toward gaining insights into how these two parts of the cell communicate and function collaboratively to realize growth, greening, flowering, and other functions.

When you change light or temperature, genes in both the nucleus and chloroplasts change their expression. We think HEMERA and RCB are involved coordinating gene expression between these two cell compartments.

Meng Chen, Plant Sciences Professor, University of California, Riverside

Eventually, the aim is to be able to tune the temperature response to guarantee the future of food supply for humans.

We were excited to find this second gene. It’s a new piece of the puzzle. Once we understand how it all works, we can modify it, and help crops cope better with climate change.

Meng Chen, Plant Sciences Professor, University of California, Riverside

Journal Reference:

Qiu, Y., et al. (2021) RCB initiates Arabidopsis thermomorphogenesis by stabilizing the thermoregulator PIF4 in the daytime. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22313-x.