Ocean food webs depend on copepods, which have the ability to genetically adjust to warmer and more acidic waters. This is the outcome of a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

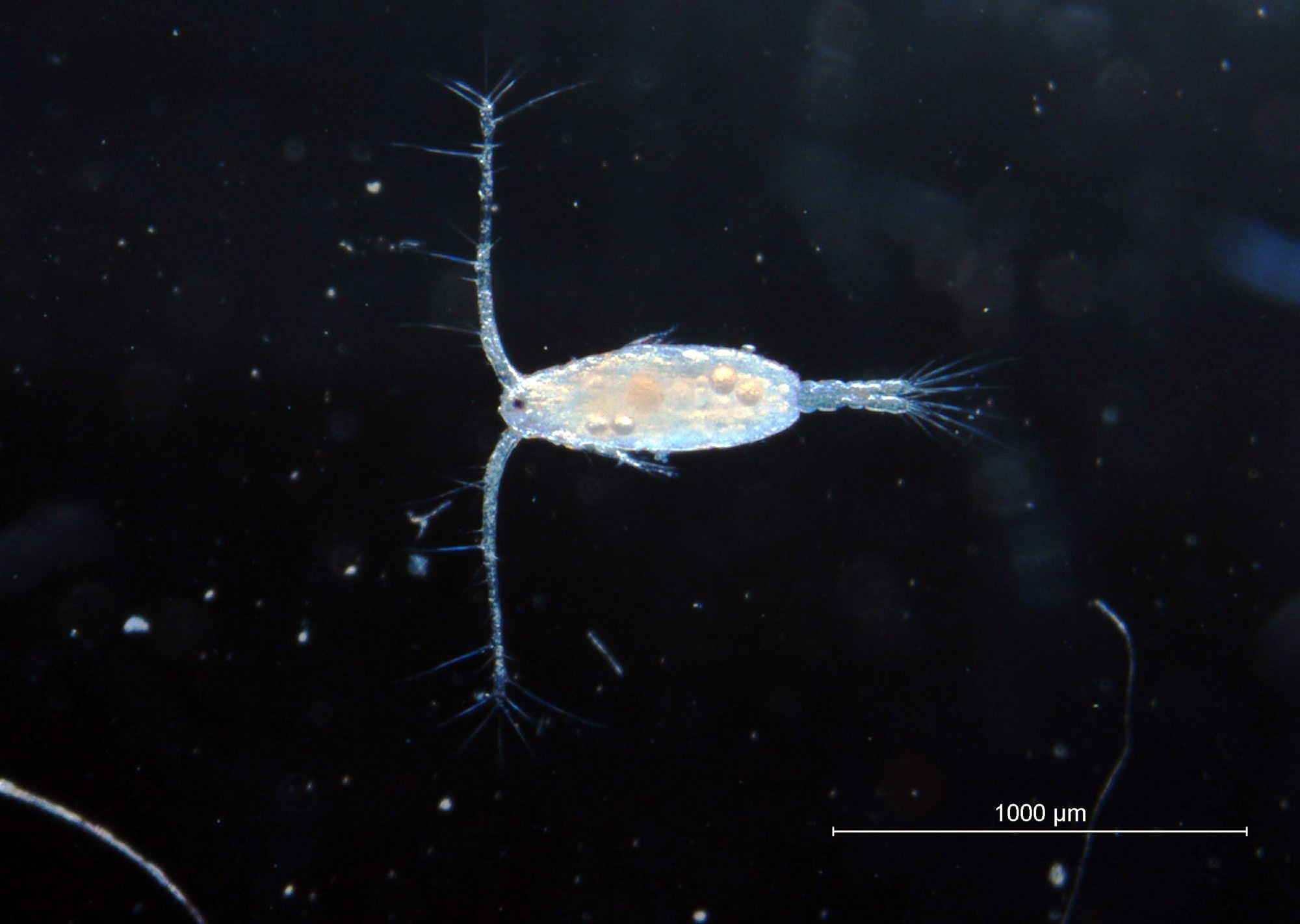

Copepod enlarged. Copepods are an important component of the marine food web. Image Credit: Alexandra Hahn/GEOMAR

Copepod enlarged. Copepods are an important component of the marine food web. Image Credit: Alexandra Hahn/GEOMAR

One of the most significant marine animals is the copepod. The microscopic creatures are crucial to sea life because they provide food for numerous fish species. Marine biologists worry that small crustaceans may be negatively impacted by climate change in the future.

Whether copepods can genetically adapt to altering living conditions throughout evolution has been thoroughly examined for the first time by a team from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, the University of Connecticut, and the University of Vermont.

They have considered the impact of ocean acidification and increasing water temperatures. The US-German group’s study is noteworthy since it was among the first to subject marine animals to various stresses in a laboratory setting.

The findings are tentatively positive.

The team, led by Dr. Reid Brennan, Marine Ecologist at GEOMAR, and Dr. Melissa Pespeni, Professor at the University of Vermont, discovered through extensive genetic analysis that the small crustaceans can adapt to the new conditions throughout approximately 25 generations, or just over a year, given that several generations of crustaceans can mature in a year at moderate water temperatures.

The scientists discovered that the copepods’ genomes progressively contain gene variations that make the organisms more resilient to environmental stress as water temperatures increase and the environment becomes more acidic.

These mechanisms help, among other things, to ensure that copepod eggs develop properly despite unfavorable environmental conditions and that important metabolic processes continue.

Dr Reid Brennan, Marine Ecologist, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel

Multiple Stress Factors Amplify the Effect

The team looked at two aspects of the study: how each of the two factors individually affected the animals; and how the two factors interacted. A comparison determined that warming has a substantially bigger impact than acidification.

As a result, significantly more genes respond to heat, and the frequency of variations changes. The effect was even more pronounced when the researchers subjected the copepods to warmth and acidity.

The researchers uncovered a startling discovery: it would have been reasonable to assume that under conditions of combined heat and acid stress, genes that are responsive to heat and those that are sensitive to acidification would alter, or that the two would simply add up.

However, several additional genes responded to the dual stress. This implies that for copepods, metabolic stress keeps rising and adaptation will become increasingly more challenging.

Dr. Brennan added, “The results also show us that we have a hard time assessing how organisms will respond to an increasingly changing marine environment when multiple stressors interact.”

Even if we know how individual stressors work, it is going to be challenging to predict how the organism will respond when, for example, oxygen or nutrient deficiencies are added to the mix.

Dr Melissa Pespeni, Professor, University of Vermont

Dr. Pespeni stated, “One plus one doesn’t always equal two when it comes to global change stressors.”

This could be extremely problematic for creatures unable to reproduce and adjust to changing environmental conditions as quickly as copepods. Other factors will be looked into in future tests to learn more about the hazy future of marine species.

This study builds on a prior one by the same team, led by Professor Dr. Hans Dam from the University of Connecticut, which showed that creatures can quickly adapt to ocean warming and acidity, but only to a limited extent.

The National Science Foundation (USA) financed this publication, the most recent in a series of studies.

Journal Reference

Brennan, R. S., et al. (2022) Experimental evolution reveals the synergistic genomic mechanisms of adaptation to ocean warming and acidification in a marine copepod. PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.2201521119.