Jan 9 2020

Seven wastewater treatment plants located in the Eastern United States were recently studied, showing a mixed record with regard to removing pharmaceutical drugs like antidepressants and antibiotics.

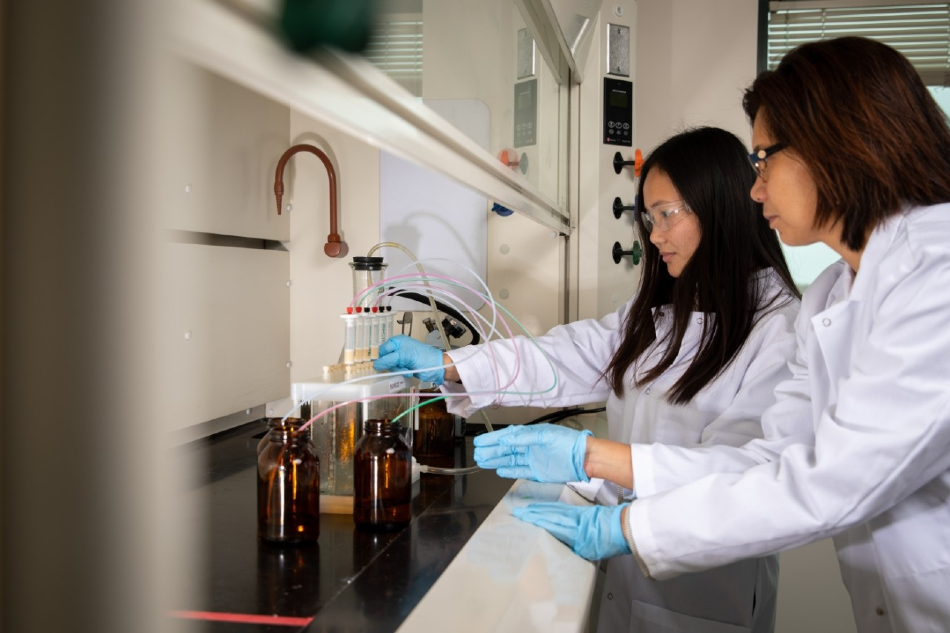

UB chemistry professor Diana Aga (right) and UB chemistry PhD candidate Luisa Angeles in the lab. To study pharmaceuticals in wastewater, they use the system pictured to isolate chemical compounds from the wastewater. Image Credit: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki.

UB chemistry professor Diana Aga (right) and UB chemistry PhD candidate Luisa Angeles in the lab. To study pharmaceuticals in wastewater, they use the system pictured to isolate chemical compounds from the wastewater. Image Credit: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki.

The study emphasized that two treatment techniques, ozonation, and granular activated carbon, are specifically promising. The researchers’ analysis showed that each method was able to decrease the concentration of many drugs, including specific antibiotics and antidepressants, present in water by over 95%.

A common treatment process called activated sludge utilizes microbes in order to disintegrate organic contaminants. Although this process serves a crucial purpose in wastewater treatment, it was relatively less effective when it came to destroying persistent medicines such as antibiotics and antidepressants.

The take-home message here is that we could actually remove most of the pharmaceuticals we studied. That’s the good news. If you really want clean water, there are multiple ways to do it.

Diana Aga, PhD, Henry M. Woodburn Professor, Department of Chemistry, College of Arts and Sciences, University at Buffalo

Aga continued, “However, for plants that rely on activated sludge only, more advanced treatment like granular activated carbon and/or ozonation may be needed. Some cities are already doing this, but it can be expensive.”

This discovery is crucial as any drug released from the wastewater treatment plants can potentially enter the environment, where they can be ingested by wildlife or contribute to phenomena such as antibiotic resistance.

Our research adds to a growing body of work showing that advanced treatment methods, including ozonation and activated carbon, can be very effective at removing persistent pharmaceuticals from wastewater.

Anne McElroy, PhD, Professor and Associate Dean for Research, School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University

The study was published in the Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology journal in November 2019, and funded by New York Sea Grant.

The study was headed by Aga and McElroy along with Luisa Angeles, a chemistry PhD student from the University at Buffalo (UB) and the first author of the study.

The project was a collaboration between scientists at Stony Brook University, UB, the Hampton Roads Sanitation District, as well as Hazen and Sawyer—a national water engineering company that develops wastewater treatment systems, including a few systems that were analyzed.

The study investigated different types of technologies being utilized at seven wastewater treatment plants located in the Eastern United States, such as a single large pilot-scale plant and six full-scale plants.

“More precise locations are not provided in order to protect the identity” of the wastewater treatment facilities,” according to the study.

The research findings can guide upcoming decision-making, specifically in water-scarce areas and in cities, that may prefer to recycle wastewater, changing it into drinking water, stated Angeles.

Moreover, the study is crucial for conserving the environment. For example, it showed that exposure to wastewater released from treatment plants did not change the behavior of larval zebrafish. However, more research is required to figure out how exposures over the longer term would have an impact on wildlife, added Aga.

In a previous study performed in 2017, Aga’s research team identified that the brains of various fish inhabiting the Niagara River—part of the Great Lakes region—showed increased concentrations of antidepressants or the metabolized remains of those medicines.

Researchers are yet to fully comprehend the ecological and behavioral impacts that are likely to take place when chemicals released from human medicines accumulate in wild animals over time, Aga further added.

Although wastewater treatment plants were previously developed and operated for various purposes like eliminating nitrogen and organic matter from used water, the latest study and other previous studies showed that such treatment facilities could also be leveraged to eliminate drugs of different classes.